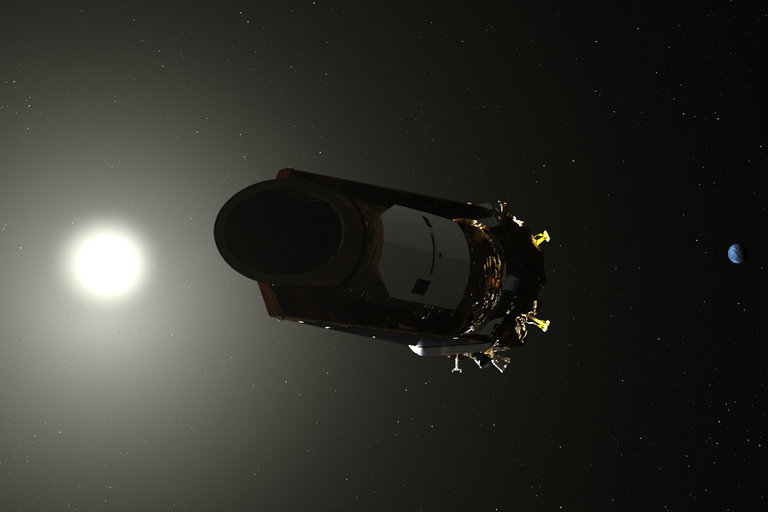

The Kepler mission, which launched in 2009, has transformed our understanding of our place in the galaxy, giving us hope that we aren’t alone. The venerable spacecraft has proved adept at reinventing itself when things go wrong. But engineers monitoring Kepler announced that the mission will soon come to an end because the spacecraft is running out of fuel.

“We’ve always known that Kepler’s lifetime would be limited by the amount of fuel in the tank,” said Thomas Barclay, a former senior research scientist with the Kepler and K2 missions. “It looks like it’s going happen at some point in the next few months, although we still don’t know exactly when.”

Barclay said the timing of when the thruster fuel tank will be empty is somewhat difficult to estimate.

“We can’t actually measure how much fuel is left,” he told Seeker in a phone call. “The engineers have to measure how much pressure there is when the thrusters are fired. So it is a bit of an art to working out how much fuel there is and how long it will last. Even with the last little bit of fuel you don’t know if it will be useable or if it will be stuck in the bottom of the tank.”

Although the spacecraft team has long known about the fuel situation, Charlie Sobeck, a system engineer for Kepler made the announcement this week.

“The Kepler space telescope has survived many potential knock-outs during its nine years in flight, from mechanical failures to being blasted by cosmic rays,” Sobeck wrote. “At this rate, the hardy spacecraft may reach its finish line in a manner we will consider a wonderful success. But with nary a gas station to be found in deep space, the spacecraft is going to run out of fuel.”

But, Sobeck added: “We’ve been surprised by its performance before.”

Kepler revolutionized what we know about the amount of exoplanets in our galaxy. The space-based telescope has detected 2,245 exoplanets with another 2,342 waiting to be confirmed.

Statistical analysis of data from the planet-hunting spacecraft reveals mind-boggling numbers: Our galaxy has at least 100 billion planets, and about 17 percent of stars have an Earth-sized planet. That means there are at least 17 billion Earth-sized worlds out there.

Kepler detected planetary candidates using the transit method, watching for a planet to cross its star and create a mini-eclipse that dims the star slightly. To do this in its Earth-trailing orbit 94 million miles away, Kepler needed to have precise pointing to constantly view a 100-square-degree portion of the sky — equivalent in size to two side-by-side “bowls” of the Big Dipper — in a star-filled region located between the constellations Cygnus and Lyra.

The mission was a spectacular success, making the announcements of spectacular worlds orbiting other stars become almost routine.

But in May of 2013, a second of Kepler’s four reaction wheels failed. These gyroscope-like devices kept the spacecraft stable, and Kepler needed at least three to be able to point accurately enough to hunt for exoplanets.

But the spacecraft wasn’t dead yet. Engineers came up with a plan to use solar radiation pressure — the photons from the sun that can be used to power solar sails — to help stabilize that spacecraft. While the telescope’s aim wasn’t as precise as it used to be, it was close. It remained a great telescope in space, and it just needed a new mission. So a group of scientists came up with a plan called K2, which Barclay described as a spectacular success in its own right.

“While the Kepler mission entailed a very focused science goal of finding exoplanets, K2 is a completely different beast,” he said. “We’re not just Kepler slightly worse at pointing; we were a revolutionary new mission.”

K2 has been run by the community of scientists around the world, one of the few NASA missions to lack a particular science goal. Instead, a panel of scientists decides how the spacecraft will be used, choosing from submitted proposals.

Proposed missions are based on the 83-day region of sky where Kepler can point.

Barclay led the K2 “guest observer” program that looked at everything from giant black holes to planets in our own solar system to supernovas in distant galaxies.

Kepler's thrusters are powered by hydrazine fuel, which has been used as a propellent since the early days of space flight. It's the same fuel that powered the Cassini spacecraft, a mission that came to an end in September 2017 when the probe ran out of fuel.

When Kepler launched, it had with 12 kilograms, or a little over 3 gallons of fuel onboard. The primary mission was planned to be three and a half years, with outside goal of operating the spacecraft for six years. Engineers said based on the amount of fuel that has been used over the course of its nine years in flight, they estimated that 2018 would be the year when the spacecraft’s fuel supplies would run out.

“We have been maintaining a close watch on the fuel estimates so that we can be prepared to bring the last batch of scientific data back to Earth and retire the spacecraft,” the team wrote.

Read more at Seeker

No comments:

Post a Comment