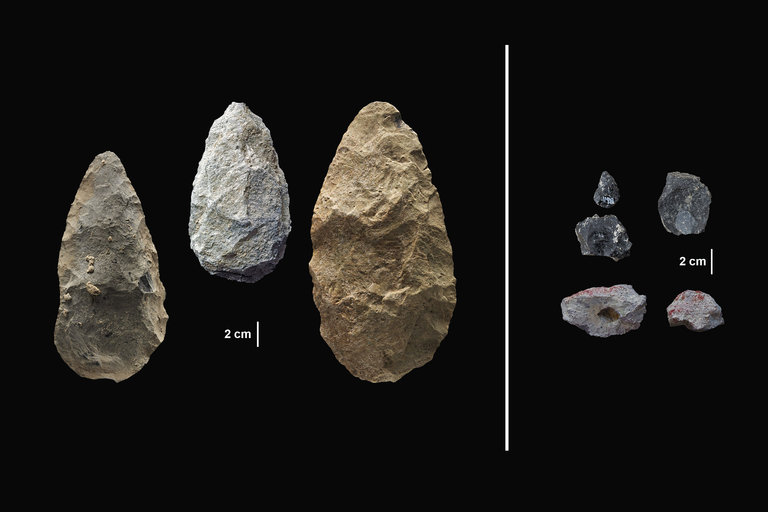

Obsidian also revolutionized the creation of other tools, including weapons. The hefty hand-axes associated with the Acheulean industries, which began over a million years ago, were gradually replaced with lighter-weight, razor-edged triangular points that could be hafted to wood or bone and projected through the air.

"The world has never been the same since," Richard Potts, director of the National Museum of Natural History's human origins program, told Seeker. Potts has been leading the program's research in the Olorgesailie Basin of southern Kenya for 34 years in collaboration with the National Museums of Kenya.

In three new studies published in the journal Science, he and his colleagues report evidence from this region of not only major technological changes, like the usage of obsidian, but also environmental and ecological changes that were also taking place before and during the period when Homo sapiens emerged.

The changes coincide with the oldest known fossil record for our species in Africa, suggesting that the events were all driving forces in the evolution of Homo sapiens.

The findings counter a popular theory about human evolution, which holds that our species gradually changed in response to environmental pressures caused by expanding, arid grasslands in Africa. The so-called savanna hypothesis suggests that our ancestors transitioned from an arboreal to a bipedal lifestyle and evolved in other key ways due to living in this type of relatively stable environment.

Potts several years ago instead formulated a human evolution theory around "variability selection," which he explained "is a process linking adaptive change to large degrees of environment variability."

In the first of the three new studies, Potts and his team report that the Olorgesailie Basin — where hominids lived starting by at least 1.2 million years ago — was mostly floodplains until around 800,000 years ago. For the next several thousand years, an increasing pace of environmental change is seen in the geological record, such as through sediments and carbon isotopes of soil samples.

"The region went from being a stable system to one with significant tectonic activity, land-lake oscillations, fire-reddened zones, and intense wet-dry fluctuations," Potts said. "These would have resulted in unpredictable food and water supplies that, in turn, would have led to populations attempting to expand their geographical range in search of resources."

|

| A bird's eye view of the Olorgesailie Basin in southern Kenya, which holds an archaeological record of early human life spanning more than a million years. |

"I refer to them as the 'large lawn mowers' of the time,'" Potts said, adding that a baboon, a big hippo, a zebra, some large wild pigs, and other animals also went extinct following the environmental changes.

Absent those large creatures, related taxa with smaller body sizes emerged. The authors say this is another sign of climate variability.

As for hominids, they could no longer stay in one place for a long time, which was a problem because of their reliance on bulky stone tools for survival.

"What we see is the emergence of smaller and lighter tools, capable of easier transport," Potts said. "These gradually replaced the big, clunky Acheulean toolkit."

This technological shift, marking the beginning of the Middle Stone Age, was previously thought to have happened around 280,000 years ago. While hominid populations throughout much of Africa appear to have held on to their Acheulean tools until that time, those in East Africa made the transition by at least 320,000 years ago. At this time, about 42 percent of the more refined tools were crafted from obsidian.

|

| Richard Potts surveys an assortment of Early Stone Age hand-axes discovered in the Olorgesailie Basin, Kenya. |

She and her team surprisingly found that there is no local source there for obsidian, which means individuals must have traveled from around 16 to over 62 miles to obtain this coveted material. The shortest distance would have required scaling a mountain, Brooks said, making the trip all the more arduous.

"Other people were also living where the obsidian was, so the travelers could not just take and grab it," Brooks told Seeker. "Instead, the humans of the Olorgesailie Basin must have made distant contacts, with whom they might have engaged in trade."

"People at the time did not have money or animals to trade," she continued. "Friends were the real money in the bank."

Before around 320,000 years ago, these populations were not yet Homo sapiens, the researchers believe. It is likely that they were Homo heidelbergensis, a species of our genus that once lived in not only Africa but also in Europe and western Asia.

Fossils for Homo sapiens start to appear in Morocco around 315,000 years ago. A skull for Homo sapiens from Ethiopia dates to around 200,000 years ago, while a jawbone from our species excavated in Israel dates to about 180,000 years ago.

As more fossils are found, it is likely that more will date closer to 320,000 years ago, coinciding with the environmental and technological changes that were also occurring at this time. As Brooks indicated, social changes were occurring too, and there are clues for this in the fossil record.

Brooks and her team report the discovery of two lumps of ochre that had been manipulated by humans. It looks as though someone ground portions of the ochre, which would have produced a bright red powder.

"This powder could be mixed with anything — sweat, oil, water, fat — and produced a nice pigment," Brooks said.

|

| Black and red rocks containing manganese and ocher were excavated at the Olorgesailie Basin, along with evidence that the rocks had been processed for use as coloring material. |

Early humans could have applied color to signify their social networks. Potts pointed out that this still occurs today with flags, tattoos, hats, university t-shirts, and other visual signs of affiliation.

"Placing color on skin, hair, and other parts of the body can be a symbolic behavior," Potts explained. "It can communicate, 'I'm part of a group that you know and you like us.'"

Conflicts occur among hunter-gatherers, but since smaller populations were spread over vast distances in Africa, the researchers believe that warfare during these earlier periods of human history would have been inherently kept in check.

This is not to say that the different hunter-gatherer groups did not have arguments. Spoken language cannot be preserved in the fossil record, save for evidence that a hominid possessed anatomy capable of speech. The researchers, however, suspect that the emergence of more complex social networks over longer distances and resulting symbolic behaviors would have advanced language evolution.

Humans in Africa probably did not talk much about killing large animals for sustenance. With many big animal species extinct and replaced by smaller taxa, people appear to have relied more on small game.

Read more at Seeker

No comments:

Post a Comment