Apr 21, 2018

Homemade microscope reveals how a cancer-causing virus clings to our DNA

"The reason we can't get rid of these [viruses] is because we can't figure out a way to get their DNA out of the nucleus, out of the cell," explained UVA researcher Dean H. Kedes, MD, PhD. "They depend on this 'tether' to remain anchored to the DNA within our cells, and to remain attached even as the cells divide. This tether is a key factor to disrupt in devising a cure."

Now that scientists can understand this vital infrastructure, they can work to disassemble it. "Without it," Kedes noted, "the virus is going to lose its hold in the body. ... Bad for the virus, but very good for the patient."

Homemade Microscope

The researchers used the microscope built by fellow investigator M. Mitchell Smith, PhD, to reveal the structure of the tether used by a virus called Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). Until now, such tethers have largely eluded scientists because they are so diabolically small, defying even the most high-tech approaches to determining their form. "We're seeing things on the order of 8,000 times smaller than a human hair," said Smith, who built UVA's microscope piece-by-piece based on one pioneered in the Physics and Astronomy Department at the University of Maine.

Smith's microscope is nothing like the simple light microscope seen in every high school biology class. It's a stunning marriage of stainless steel and laser beams, looking much like an oversized sci-fi Erector set. It sits on a table that almost fills a small room.

"It's a set of lasers, a bunch of optics that focus and filter the lasers," Smith explained, gesturing to various components. "I'm trained as a molecular geneticist, not as an optical physicist ... so we worked on it for maybe three years. But it's continually a work in progress."

The device has already proved a game-changer, allowing him and Kedes to unveil the viral tether. The researchers -- in UVA's Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology -- used fluorescent antibodies to mark individual molecules on the tether and then recorded their location in space. They then combined the resulting images to create an outline of the shape, a bit like mapping a city from thousands of GPS signals.

To complete their 3D portrait, they combined their results with information drawn from other imaging techniques, such as X-ray crystallography. The result is the most complete portrait of the tether ever created. And that information likely will prove vital for cutting the rope on the virus' grappling hook.

The researchers envision using the approach for many other stubborn viruses, such as Epstein-Barr (the virus that causes infectious mononucleosis) and HPV (human papillomavirus). Further, they suspect that such viruses' tethers may share similarities with the one they revealed. "Now, for the first time," Kedes said, "it's OK to say, 'Let's focus on structures that are vital to the virus that before were below the limits of our standard methods of detection within infected cells.'"

Findings Published

The researchers have published their findings in the scientific journal PNAS, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The research team consisted of Margaret J. Grant, Matthew S. Loftus, Aiola P. Stoja, Kedes and Smith.

Read more at Science Daily

Animal Advocates and Academics Seek Personhood Rights for Chimpanzees

When legal scholar Steven Wise first found Tommy, the male chimpanzee was living alone in a shed on a used trailer lot along Route 30 in Gloversville, New York. Believed to have been born in the early 1980s, Tommy was raised from infancy by David Sabo, proprietor of a circus troupe. When Sabo died in 2008, at least some of the chimps in his care, according to Wise, went to the owners of the trailer business.

Five years ago, Wise's Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) — a legal advocacy group for animals — filed a petition calling for, in part, Tommy's "immediate release from illegal detention." The petition further said: "Respondents are detaining Tommy in solitary confinement in a small, dank, cement cage in a cavernous dark shed ... ."

Based on the Animal Welfare Act (AWA), Tommy's owners appear to be in full compliance with federal law, which says that chimps, under certain conditions, can be housed alone and in cages. Nevertheless, Tommy's "confinement constitutes a profound harm that demands remedy by the courts," Gary Comstock, a professor of philosophy at North Carolina State University, told Seeker.

In February, Comstock and 16 other philosophers co-authored an amicus brief in support of an NhRP motion seeking habeas corpus relief for Tommy and another chimpanzee named Kiko. The New York State Court of Appeals is weighing whether or not to allow the suit to proceed. NhRP argues that chimpanzees like Tommy and Kiko should be recognized as a "person," since under current US law, one is either a person or a thing. Wise, president of the NhRP, explained that things "lack the capacity for any legal rights. Welfare protections do not alter this fact."

Brief co-author David Peña-Guzmán of California State University, San Francisco, told Seeker: "I think most people resist the notion of personhood mainly because they are not aware that the only alternative to it is thinghood. If you ask most people whether animals are analogous to things such as chairs and desks, most will emphatically say 'no.' If you then ask them whether animals can have rights, many will say 'yes.' These two answers add up to personhood."

According to Wise and the philosophers, the fight over Tommy highlights a persistent yet urgent problem concerning US law that treats nonhuman animals as things despite growing scientific evidence and societal acceptance that they are intelligent, sensitive, and social beings that can even at times communicate their feelings to humans.

Brief co-author Kristin Andrews of York University, for example, told Seeker that another chimp named Bruno learned sign language at the University of Oklahoma during research on communication. When funding for the project ran out, he was sent to a biomedical facility. Researcher Mark Bodamer of the university project later visited the chimp. Andrews said, "Bruno, who hadn't signed while at the biomedical facility, started signing when he saw Mark. What did he say? Key out!"

L. Syd Johnson of Michigan Technological University, who is another author of the brief, said there have been many times in human history where hierarchies of humans have been established, sometimes by skin color, sex, age, religion, and having or not having certain abilities.

"On the 'thing' side of the divide, at various times in history, slaves, women, and children have been regarded as things and not persons," Wise said. "It took a mighty social struggle to move each of these beings into the class of rights-bearers — persons."

He added, "A person need not have the full suite of human rights, either. Corporations are persons but cannot marry, for example. Personhood is a tremendously flexible concept in the law. No third option is needed."

The European Union, however, has a third option in place.

Brief co-author Andrew Fenton of Dalhousie University told Seeker that the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, otherwise known as the Lisbon Treaty, recognizes nonhuman animals as "sentient beings,” but the treaty does not offer nonhuman primates full protections. For example, a stipulation allows that if there were "an unexpected outbreak of a life-threatening or debilitating clinical condition in human beings," nonhuman great apes could be used in research.

Peña-Guzmán said that if a third term like "sentient beings" could give chimpanzees the same protections as the term "person," then it is not even necessary to have this other wording in the first place.

If the third term does not afford the same protections, then "it is not as good," he said.

He continued, "What matters to us, ultimately, is that chimpanzees be given the right to bodily liberty, independently of what term is used. In the US at this moment in history, the only category that does this is 'person.'"

Andrews and Wise told Seeker that a formal definition of a person,"in the US legal context, can be traced back to John W. Salmond's Jurisprudence, first published in 1907 and cited by the most widely used legal dictionary in the US, Black's Law Dictionary. Salmond mentions that persons are subjects of "legal rights or duties." A person is therefore a rights bearer, and one either bears rights or does not.

Implementing that seemingly simple concept turns out to be far more complicated than imagined.

Consider that an Opinion of the Court rejecting NhRP's claims about chimpanzees concluded: [U]nlike human beings, chimpanzees cannot bear any legal duties, submit to societal responsibilities, or be held legally accountable for their actions. In our view, it is this incapability to bear any legal responsibilities and societal duties that renders it inappropriate to confer upon chimpanzees the legal rights — such as the fundamental right to liberty protected by the writ of habeas corpus — that have been afforded to human beings."

A writ of habeas corpus, what NhRP is seeking for Tommy, means to "produce the body" and is a court order to show valid reason for an individual's detention. In Tommy's case, that refers to his being locked up alone in metal cage.

Johnson said that in 1874, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals even filed a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of an abused child because the law at the time did not recognize children as persons, and there were no laws then against child abuse.

If the court's criteria for personhood were to hold on every level, some of the most vulnerable people — infants, the mentally ill, people with dementia — would be considered things, not persons.

NhRP brief co-author Tyler John of Rutgers University told Seeker that the New York court's legal argument "excludes basic legal protections for some humans who morally deserve these basic legal protections. It therefore must be mistaken."

"But," he added, "we should also note that on a proper understanding of civic responsibilities, many nonhuman animals can, in fact, bear civic responsibilities. None of us were taught to obey the law from an early age through abstract philosophical reflection; we learned it through modeling of good behavior and through the good things that happen when we obey rules. Chimpanzees and other social animals can learn to obey many civic duties in the same way."

Even if there are some legal duties that certain human and nonhuman animals cannot have, this does not by itself mean that we need new legal categories for these individuals, John continued.

He added, "Children and chimpanzees deserve the legal protection of their basic rights to liberty and bodily integrity regardless of whether they can bear legal duties, and under the law this amounts to personhood."

John further pointed out that if a very young child were to refuse a lifesaving medical procedure, guardians could override the decision. No one, on the other hand, may override a human adult's clear-headed decision to refuse such a procedure.

"But this does not mean that we need to classify young children as falling between persons and things," he said.

In a recent op-ed in The New York Times, NhRP brief co-author Jeff Sebo suggests that "a more inclusive view of personhood" might take into account the following features: conscious experience, emotionality, a sense of self or bonds of care, or interdependence.

He argues that Tommy and Kiko, "are conscious, emotional, intelligent, social beings whose lives are deeply entangled with our own, their current state of isolation notwithstanding. As a result, they count as persons on any view inclusive enough to meet contemporary standards of human rights."

If Sebo's criteria for personhood were upheld, though, chimpanzees would not be the only nonhuman animals that could pass this type of test. Common pets, such as dogs and cats, clearly would, too. It is easy for us to relate to these complex and social mammals that are somewhat like ourselves.

But biases likely affect the values we place on less similar animals like fish — and insects.

"I want to allow for the possibility that insects can have rights," Sebo, director of the animals studies master's degree program at New York University, told Seeker. "If insects are conscious, and if conscious beings can have rights, then insects can have rights, even if they have different rights than humans."

"Of course," he added, "others might disagree with me about this. Either way, we can start by accepting that Kiko and Tommy can have rights and then we can ask the other, more difficult questions that follow."

The NhRP argues that autonomy is a sufficient, but not a necessary, requirement for personhood. This could lead down a slippery slope over how we judge the inherent worth of other species and even other aspects of nature. Brief co-author Robert Jones of California State University, Chico, told Seeker that many ecosystem components, such as plants, clearly play essential roles in the web of life, "but lack so-called intrinsic value."

"However," he added, "those beings who possess subjective experiences that have an attractive or aversive quality — such as pain and suffering, pleasure and joy — have an interest in not having those experiences in the way that a boulder or blade of grass does not."

Wise said that as the common law continues to evolve, there may be other criteria beyond autonomy on which to base rights for nonhuman animals. For now, his organization's focus is on seeking legal rights and personhood for not only chimpanzees, but also elephants and orcas.

NhRP has already begun litigating on behalf of elephants Minnie, Beulah, and Karen at the Commerford Zoo in Goshen, Conn. The US Department of Agriculture has cited the zoo over 50 times for failing to adhere to minimum standards required under the Animal Welfare Act, according to NhRP, which reports that the zoo continues to use bullhooks — elephant-training tools with a metal hook at the end — on the pachyderms.

While prospects for the elephants remain unknown, NhRP has made strides in other litigation. In 2015, at the behest of the organization, Justice Barbara Jaffe became the first judge in history to issue a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of two chimpanzees, Hercules and Leo. The legal document was later amended to strike out the phrase "writ of habeas corpus." Court appeals failed to obtain "legal persons" status for the chimps.

The New Iberia Research Center (NIRC), where the chimps were born in 2006, had previously leased Hercules and Leo to Stony Brook University for a study on bipedal walking. After the litigation, Hercules and Leo were returned to NIRC in 2015.

According to the journal Science, on March 21 of this year, NIRC moved the primates to the Project Chimps sanctuary in Georgia. Wise has "serious concerns" about Project Chimps. For example, he said that "there is only one outdoor area for the chimps at the site." He told Science, though, “I’m glad to hear Hercules and Leo are getting out of New Iberia."

Wise hopes that the two males can be moved to another sanctuary, Save the Chimps, which is in Florida and has offered to house the primates at no extra cost to NIRC. Like the three elephants, it remains unknown for now what will ultimately happen to these two chimps.

Jaffe's issuance of the writ of habeas corpus, however, marks a legal milestone that was followed in 2016 by a similar judgment in Argentina granting "nonhuman person" status to a chimp named Cecilia. The chimp was ordered removed from a zoo and transferred to a sanctuary.

Approximately 2,000 chimpanzees are kept in captivity in the US alone. According to the World Animal Foundation, about 300 are in zoos, and the remaining 1,700 were bred for medical research. The situation seems monumental when other animals are factored in. There are 100 million animals held captive for entertainment and research purposes, based on Humane Society International estimates.

A recent survey conducted by the Sentience Institute, which was replicated by Oklahoma State University, found that nearly 50 percent of Americans desire a ban on slaughterhouses. A recent poll commissioned by NhRP found that almost half of all participants "agreed with a statement saying that animals deserve the same rights as humans," and "about half said they would support legislation to recognize legal rights for some animals."

The legalese of personhood is hard for many people to grasp, though, and the studies indicate that the public is divided nearly 50-50 in their views of animal rights.

Richard Cupp, a professor at Pepperdine School of Law, told Seeker that he supports legal efforts to improve the welfare of animals, but said the term “animal rights” is vague.

“My experience is that many people who initially say they support 'animal rights' actually support imposing appropriate legal responsibilities on humans to prohibit mistreatment of animals, rather than supporting legal personhood and accompanying legal rights for animals," he said.

The arguments against granting animals personhood rights, he said, range from chimps lacking "a sufficient level of moral agency to be justly held legally accountable" to "the potential societal chaos" that would ensue should legal personhood be extended to nonhuman animals.

"Rejecting nonhuman animal, legal personhood does not imply being satisfied with the status quo regarding how we treat animals," Cupp said. "Society has made important advances in animal welfare in recent years, and we are probably closer to the beginning of this significant period of animal welfare, legal evolution than we are to its future high point. As a society we need to continue our evolution toward increased protection of animals, but they should not be made legal persons."

He acknowledges that lawmakers and others need to do a better job of being explicit in statutes, ordinances, and court decisions that sentient animals are different from inanimate property. "Sentience" itself is a loaded topic, but Cupp uses the word to describe animals capable of suffering.

His views of the issue will soon be published in the University of Cincinnati Law Review. A draft of the article is available online. As Cupp admits in the article, however, not granting chimpanzees and other animals personhood does mean that they are "still property" in the eyes of the law.

If the New York court eventually does issue an "order to show cause" pursuant to the writ of habeas corpus, a hearing would take place, as it did in Hercules and Leo's case, which would shift the burden of proof from the NhRP to those currently holding the chimps captive. Then, if the owners cannot justify the legality of their detainment of the chimps, the court could rule that Kiko and Tommy are legal persons with the right to bodily liberty and offer "relief," which might mean transferring the chimps to a sanctuary.

If the owners cannot prove the legality of their detainment of the chimps, the court could then offer "relief," which might mean transferring the chimps to a sanctuary. Such a ruling would likely serve as precedent for other parties to seek habeas corpus relief for other chimpanzees in New York and could lead to similar rulings in other states.

A potential complication in the New York case has to do with the current location and status of Tommy. In 2016, various media outlets including The Dodo reported that Tommy was donated to the DeYoung Family Zoo in Wallace, Michigan, in September 2015.

Brittany Peet, director of captive animal law enforcement for PETA Foundation, told Seeker that New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets records provide evidence that the donation occurred. Representatives for the zoo, which is seasonal and reopens this year on May 1, have claimed to be unfamiliar with any chimpanzee named Tommy and have not confirmed his existence.

PETA filed a complaint against the zoo in 2016, which suggests that, even though the plaintiffs deny having a chimp named Tommy, they do "have a chimpanzee" that is then referred to as "Chimpanzee number 2" as well as a chimp called "Louie." PETA even issued a petition, urging that the zoo retire their chimpanzees to a reputable sanctuary.

The number-2 terminology is a stark reminder of what can happen when animals become nameless property. Death records often follow suit, which could mean that if Tommy did die, his name — and therefore the loss of him as a unique individual — might never be known.

Wise, however, said, "We have a strong basis for believing Tommy is alive and still in New York."

If that is the case, his condition remains unknown.

As for Kiko, NhRP believes that he is now in a cage in a cement storefront attached to a home in a residential area of Niagra Falls, New York. Whatever one thinks of this unusual arrangement, no welfare law appears to have been violated with the confinement of Kiko and Tommy.

"But this does not mean that their conditions of life are morally acceptable as they currently stand," Peña-Guzmán said.

Read more at Seeker

Five years ago, Wise's Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) — a legal advocacy group for animals — filed a petition calling for, in part, Tommy's "immediate release from illegal detention." The petition further said: "Respondents are detaining Tommy in solitary confinement in a small, dank, cement cage in a cavernous dark shed ... ."

Based on the Animal Welfare Act (AWA), Tommy's owners appear to be in full compliance with federal law, which says that chimps, under certain conditions, can be housed alone and in cages. Nevertheless, Tommy's "confinement constitutes a profound harm that demands remedy by the courts," Gary Comstock, a professor of philosophy at North Carolina State University, told Seeker.

In February, Comstock and 16 other philosophers co-authored an amicus brief in support of an NhRP motion seeking habeas corpus relief for Tommy and another chimpanzee named Kiko. The New York State Court of Appeals is weighing whether or not to allow the suit to proceed. NhRP argues that chimpanzees like Tommy and Kiko should be recognized as a "person," since under current US law, one is either a person or a thing. Wise, president of the NhRP, explained that things "lack the capacity for any legal rights. Welfare protections do not alter this fact."

Brief co-author David Peña-Guzmán of California State University, San Francisco, told Seeker: "I think most people resist the notion of personhood mainly because they are not aware that the only alternative to it is thinghood. If you ask most people whether animals are analogous to things such as chairs and desks, most will emphatically say 'no.' If you then ask them whether animals can have rights, many will say 'yes.' These two answers add up to personhood."

According to Wise and the philosophers, the fight over Tommy highlights a persistent yet urgent problem concerning US law that treats nonhuman animals as things despite growing scientific evidence and societal acceptance that they are intelligent, sensitive, and social beings that can even at times communicate their feelings to humans.

Brief co-author Kristin Andrews of York University, for example, told Seeker that another chimp named Bruno learned sign language at the University of Oklahoma during research on communication. When funding for the project ran out, he was sent to a biomedical facility. Researcher Mark Bodamer of the university project later visited the chimp. Andrews said, "Bruno, who hadn't signed while at the biomedical facility, started signing when he saw Mark. What did he say? Key out!"

|

| Tommy, a chimpanzee, is seen in Unlocking the Cage, a film by Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker. |

"On the 'thing' side of the divide, at various times in history, slaves, women, and children have been regarded as things and not persons," Wise said. "It took a mighty social struggle to move each of these beings into the class of rights-bearers — persons."

He added, "A person need not have the full suite of human rights, either. Corporations are persons but cannot marry, for example. Personhood is a tremendously flexible concept in the law. No third option is needed."

The European Union, however, has a third option in place.

Brief co-author Andrew Fenton of Dalhousie University told Seeker that the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, otherwise known as the Lisbon Treaty, recognizes nonhuman animals as "sentient beings,” but the treaty does not offer nonhuman primates full protections. For example, a stipulation allows that if there were "an unexpected outbreak of a life-threatening or debilitating clinical condition in human beings," nonhuman great apes could be used in research.

Peña-Guzmán said that if a third term like "sentient beings" could give chimpanzees the same protections as the term "person," then it is not even necessary to have this other wording in the first place.

If the third term does not afford the same protections, then "it is not as good," he said.

He continued, "What matters to us, ultimately, is that chimpanzees be given the right to bodily liberty, independently of what term is used. In the US at this moment in history, the only category that does this is 'person.'"

Andrews and Wise told Seeker that a formal definition of a person,"in the US legal context, can be traced back to John W. Salmond's Jurisprudence, first published in 1907 and cited by the most widely used legal dictionary in the US, Black's Law Dictionary. Salmond mentions that persons are subjects of "legal rights or duties." A person is therefore a rights bearer, and one either bears rights or does not.

Implementing that seemingly simple concept turns out to be far more complicated than imagined.

Consider that an Opinion of the Court rejecting NhRP's claims about chimpanzees concluded: [U]nlike human beings, chimpanzees cannot bear any legal duties, submit to societal responsibilities, or be held legally accountable for their actions. In our view, it is this incapability to bear any legal responsibilities and societal duties that renders it inappropriate to confer upon chimpanzees the legal rights — such as the fundamental right to liberty protected by the writ of habeas corpus — that have been afforded to human beings."

|

| Lawyer Steven Wise is seen in court in Unlocking the Cage, a film by Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker. |

Johnson said that in 1874, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals even filed a writ of habeas corpus on behalf of an abused child because the law at the time did not recognize children as persons, and there were no laws then against child abuse.

If the court's criteria for personhood were to hold on every level, some of the most vulnerable people — infants, the mentally ill, people with dementia — would be considered things, not persons.

NhRP brief co-author Tyler John of Rutgers University told Seeker that the New York court's legal argument "excludes basic legal protections for some humans who morally deserve these basic legal protections. It therefore must be mistaken."

"But," he added, "we should also note that on a proper understanding of civic responsibilities, many nonhuman animals can, in fact, bear civic responsibilities. None of us were taught to obey the law from an early age through abstract philosophical reflection; we learned it through modeling of good behavior and through the good things that happen when we obey rules. Chimpanzees and other social animals can learn to obey many civic duties in the same way."

Even if there are some legal duties that certain human and nonhuman animals cannot have, this does not by itself mean that we need new legal categories for these individuals, John continued.

He added, "Children and chimpanzees deserve the legal protection of their basic rights to liberty and bodily integrity regardless of whether they can bear legal duties, and under the law this amounts to personhood."

John further pointed out that if a very young child were to refuse a lifesaving medical procedure, guardians could override the decision. No one, on the other hand, may override a human adult's clear-headed decision to refuse such a procedure.

"But this does not mean that we need to classify young children as falling between persons and things," he said.

In a recent op-ed in The New York Times, NhRP brief co-author Jeff Sebo suggests that "a more inclusive view of personhood" might take into account the following features: conscious experience, emotionality, a sense of self or bonds of care, or interdependence.

He argues that Tommy and Kiko, "are conscious, emotional, intelligent, social beings whose lives are deeply entangled with our own, their current state of isolation notwithstanding. As a result, they count as persons on any view inclusive enough to meet contemporary standards of human rights."

If Sebo's criteria for personhood were upheld, though, chimpanzees would not be the only nonhuman animals that could pass this type of test. Common pets, such as dogs and cats, clearly would, too. It is easy for us to relate to these complex and social mammals that are somewhat like ourselves.

But biases likely affect the values we place on less similar animals like fish — and insects.

"I want to allow for the possibility that insects can have rights," Sebo, director of the animals studies master's degree program at New York University, told Seeker. "If insects are conscious, and if conscious beings can have rights, then insects can have rights, even if they have different rights than humans."

"Of course," he added, "others might disagree with me about this. Either way, we can start by accepting that Kiko and Tommy can have rights and then we can ask the other, more difficult questions that follow."

The NhRP argues that autonomy is a sufficient, but not a necessary, requirement for personhood. This could lead down a slippery slope over how we judge the inherent worth of other species and even other aspects of nature. Brief co-author Robert Jones of California State University, Chico, told Seeker that many ecosystem components, such as plants, clearly play essential roles in the web of life, "but lack so-called intrinsic value."

"However," he added, "those beings who possess subjective experiences that have an attractive or aversive quality — such as pain and suffering, pleasure and joy — have an interest in not having those experiences in the way that a boulder or blade of grass does not."

Wise said that as the common law continues to evolve, there may be other criteria beyond autonomy on which to base rights for nonhuman animals. For now, his organization's focus is on seeking legal rights and personhood for not only chimpanzees, but also elephants and orcas.

NhRP has already begun litigating on behalf of elephants Minnie, Beulah, and Karen at the Commerford Zoo in Goshen, Conn. The US Department of Agriculture has cited the zoo over 50 times for failing to adhere to minimum standards required under the Animal Welfare Act, according to NhRP, which reports that the zoo continues to use bullhooks — elephant-training tools with a metal hook at the end — on the pachyderms.

|

| Minnie the elephant performing at Commerford Zoo, Goshen, Conn. |

The New Iberia Research Center (NIRC), where the chimps were born in 2006, had previously leased Hercules and Leo to Stony Brook University for a study on bipedal walking. After the litigation, Hercules and Leo were returned to NIRC in 2015.

According to the journal Science, on March 21 of this year, NIRC moved the primates to the Project Chimps sanctuary in Georgia. Wise has "serious concerns" about Project Chimps. For example, he said that "there is only one outdoor area for the chimps at the site." He told Science, though, “I’m glad to hear Hercules and Leo are getting out of New Iberia."

Wise hopes that the two males can be moved to another sanctuary, Save the Chimps, which is in Florida and has offered to house the primates at no extra cost to NIRC. Like the three elephants, it remains unknown for now what will ultimately happen to these two chimps.

Jaffe's issuance of the writ of habeas corpus, however, marks a legal milestone that was followed in 2016 by a similar judgment in Argentina granting "nonhuman person" status to a chimp named Cecilia. The chimp was ordered removed from a zoo and transferred to a sanctuary.

Approximately 2,000 chimpanzees are kept in captivity in the US alone. According to the World Animal Foundation, about 300 are in zoos, and the remaining 1,700 were bred for medical research. The situation seems monumental when other animals are factored in. There are 100 million animals held captive for entertainment and research purposes, based on Humane Society International estimates.

A recent survey conducted by the Sentience Institute, which was replicated by Oklahoma State University, found that nearly 50 percent of Americans desire a ban on slaughterhouses. A recent poll commissioned by NhRP found that almost half of all participants "agreed with a statement saying that animals deserve the same rights as humans," and "about half said they would support legislation to recognize legal rights for some animals."

The legalese of personhood is hard for many people to grasp, though, and the studies indicate that the public is divided nearly 50-50 in their views of animal rights.

Richard Cupp, a professor at Pepperdine School of Law, told Seeker that he supports legal efforts to improve the welfare of animals, but said the term “animal rights” is vague.

“My experience is that many people who initially say they support 'animal rights' actually support imposing appropriate legal responsibilities on humans to prohibit mistreatment of animals, rather than supporting legal personhood and accompanying legal rights for animals," he said.

The arguments against granting animals personhood rights, he said, range from chimps lacking "a sufficient level of moral agency to be justly held legally accountable" to "the potential societal chaos" that would ensue should legal personhood be extended to nonhuman animals.

"Rejecting nonhuman animal, legal personhood does not imply being satisfied with the status quo regarding how we treat animals," Cupp said. "Society has made important advances in animal welfare in recent years, and we are probably closer to the beginning of this significant period of animal welfare, legal evolution than we are to its future high point. As a society we need to continue our evolution toward increased protection of animals, but they should not be made legal persons."

He acknowledges that lawmakers and others need to do a better job of being explicit in statutes, ordinances, and court decisions that sentient animals are different from inanimate property. "Sentience" itself is a loaded topic, but Cupp uses the word to describe animals capable of suffering.

His views of the issue will soon be published in the University of Cincinnati Law Review. A draft of the article is available online. As Cupp admits in the article, however, not granting chimpanzees and other animals personhood does mean that they are "still property" in the eyes of the law.

If the New York court eventually does issue an "order to show cause" pursuant to the writ of habeas corpus, a hearing would take place, as it did in Hercules and Leo's case, which would shift the burden of proof from the NhRP to those currently holding the chimps captive. Then, if the owners cannot justify the legality of their detainment of the chimps, the court could rule that Kiko and Tommy are legal persons with the right to bodily liberty and offer "relief," which might mean transferring the chimps to a sanctuary.

If the owners cannot prove the legality of their detainment of the chimps, the court could then offer "relief," which might mean transferring the chimps to a sanctuary. Such a ruling would likely serve as precedent for other parties to seek habeas corpus relief for other chimpanzees in New York and could lead to similar rulings in other states.

A potential complication in the New York case has to do with the current location and status of Tommy. In 2016, various media outlets including The Dodo reported that Tommy was donated to the DeYoung Family Zoo in Wallace, Michigan, in September 2015.

Brittany Peet, director of captive animal law enforcement for PETA Foundation, told Seeker that New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets records provide evidence that the donation occurred. Representatives for the zoo, which is seasonal and reopens this year on May 1, have claimed to be unfamiliar with any chimpanzee named Tommy and have not confirmed his existence.

PETA filed a complaint against the zoo in 2016, which suggests that, even though the plaintiffs deny having a chimp named Tommy, they do "have a chimpanzee" that is then referred to as "Chimpanzee number 2" as well as a chimp called "Louie." PETA even issued a petition, urging that the zoo retire their chimpanzees to a reputable sanctuary.

The number-2 terminology is a stark reminder of what can happen when animals become nameless property. Death records often follow suit, which could mean that if Tommy did die, his name — and therefore the loss of him as a unique individual — might never be known.

Wise, however, said, "We have a strong basis for believing Tommy is alive and still in New York."

If that is the case, his condition remains unknown.

As for Kiko, NhRP believes that he is now in a cage in a cement storefront attached to a home in a residential area of Niagra Falls, New York. Whatever one thinks of this unusual arrangement, no welfare law appears to have been violated with the confinement of Kiko and Tommy.

"But this does not mean that their conditions of life are morally acceptable as they currently stand," Peña-Guzmán said.

Read more at Seeker

Apr 20, 2018

Dogs could be more similar to humans than we thought

|

| The canine microbiome is quite similar to that of humans. |

Dr Luis Pedro Coelho and colleagues from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory, in collaboration with Nestlé Research, evaluated the gut microbiome of two dog breeds and found that the gene content of the dogs microbiome showed many similarities to the human gut microbiome, and was more similar to humans than the microbiome of pigs or mice.

Dr Luis Pedro Coelho, corresponding author of the study, commented: "We found many similarities between the gene content of the human and dog gut microbiomes. The results of this comparison suggest that we are more similar to man's best friend than we originally thought."

The researchers found that changes in the amount of protein and carbohydrates in the diet had a similar effect on the microbiota of dogs and humans, independent of the dog's breed or sex. The microbiomes of overweight or obese dogs were found to be more responsive to a high protein diet compared to microbiomes of lean dogs; this is consistent with the idea that healthy microbiomes are more resilient.

Dr Luis Pedro Coelho, commented: "These findings suggest that dogs could be a better model for nutrition studies than pigs or mice and we could potentially use data from dogs to study the impact of diet on gut microbiota in humans, and humans could be a good model to study the nutrition of dogs.

"Many people who have pets consider them as part of the family and like humans, dogs have a growing obesity problem. Therefore, it is important to study the implications of different diets."

The researchers investigated how diet interacted with the dog gut microbiome with a randomized controlled trial using a sample of 64 dogs, half of which were beagles and half were retrievers, with equal numbers of lean and overweight dogs. The dogs were all fed the same base diet of commercially available dog food for four weeks then they were randomized into two groups; one group consumed a high protein, low carb diet and the other group consumed a high carb, low protein diet for four weeks. A total of 129 dog stool samples were collected at four and eight weeks. The researchers then extracted DNA from these samples to create the dog gut microbiome gene catalogue containing 1,247,405 genes. The dog gut gene catalogue was compared to existing gut microbiome gene catalogues from humans, mice and pigs to assess the similarities in gene content and how the gut microbiome responds to changes in diet.

Read more at Science Daily

3-D human 'mini-brains' shed new light on genetic underpinnings of major mental illness

|

| Neurons |

Researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital are leveraging these new technologies to study the effects of DISC1 mutations in cerebral organoids -- "mini brains" -- cultured from human stem cells. Their results are published in Translational Psychiatry.

"Mini-brains can help us model brain development," said senior author Tracy Young-Pearse, PhD, head of the Young-Pearse Lab in the Ann Romney Center for Neurologic Diseases at BWH. "Compared to traditional methods that have allowed us to investigate human cells in culture in two-dimensions, these cultures let us investigate the three-dimensional structure and function of the cells as they are developing, giving us more information than we would get with a traditional cell culture."

The researchers cultured human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to create three-dimensional mini-brains for study. Using the gene editing tool CRISPR-Cas9, they disrupted DISC1, modeling the mutation seen in studies of families suffering from these diseases. The team compared mini-brains grown from stem cells with and without this specific mutation.

DISC1-mutant mini-brains showed significant structural disruptions compared to organoids in which DISC1 was intact. Specifically, the fluid-filled spaces, known as ventricles, in the DISC1-mutant mini-brains were more numerous and smaller than in controls, meaning that while the expected cells are present in the DISC1-mutant, they are not in their expected locations. The DISC1-mutant mini-brains also show increased signaling in the WNT pathway, a pathway known to be important for patterning organs and one that is disrupted in bipolar disorder. By adding an inhibitor of the WNT pathway to the growing DISC1-mutant mini-brains, the researchers were able to "rescue" them -- instead of having structural differences, they looked similar to the mini-brains developed from normal stem cells. This suggests that the WNT pathway may be responsible for the observed structural disruption in the DISC1-mutants, and could be a potential target pathway for future therapies.

"By producing cerebral organoids from iPSCs we are able to carefully control these experiments. We know that any differences we are seeing are because of the DISC1-mutation that we introduced," said Young-Pearse. "By looking at how DISC1-mutations disrupt the morphology and gene expression of cerebral organoids, we are strengthening the link between DISC1-mutation and major mental illness, and providing new avenues for investigation of this relationship."

Read more at Science Daily

Clear as mud: Desiccation cracks help reveal the shape of water on Mars

In early 2017 scientists announced the discovery of possible desiccation cracks in Gale Crater, which was filled by lakes 3.5 billion years ago. Now, a new study has confirmed that these features are indeed desiccation cracks, and reveals fresh details about Mars' ancient climate.

"We are now confident that these are mudcracks," explains lead author Nathaniel Stein, a geologist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. Since desiccation mudcracks form only where wet sediment is exposed to air, their position closer to the center of the ancient lake bed rather than the edge also suggests that lake levels rose and fell dramatically over time.

"The mudcracks show that the lakes in Gale Crater had gone through the same type of cycles that we see on Earth," says Stein. The study was published in Geology online ahead of print on 16 April 2018.

The researchers focused on a coffee table-sized slab of rock nicknamed "Old Soaker." Old Soaker is crisscrossed with polygons identical in appearance to desiccation features on Earth. The team took a close physical and chemical look at those polygons using Curiosity's Mastcam, Mars Hand Lens Imager, ChemCam Laser Induced Breakdown Spectrometer (LIBS), and Alpha-Particle X-Ray Spectrometer (APXS).

That close look proved that the polygons -- confined to a single layer of rock and with sediment filling the cracks between them -- formed from exposure to air, rather than other mechanisms such as thermal or hydraulic fracturing. And although scientists have known almost since the moment Curiosity landed in 2012 that Gale Crater once contained lakes, explains Stein, "the mudcracks are exciting because they add context to our understanding of this ancient lacustrine system."

"We are capturing a moment in time," he adds. "This research is just a chapter in a story that Curiosity has been building since the beginning of its mission."

From Science Daily

Stone Age Cow Underwent Cranial Surgery 5,000 Years Ago

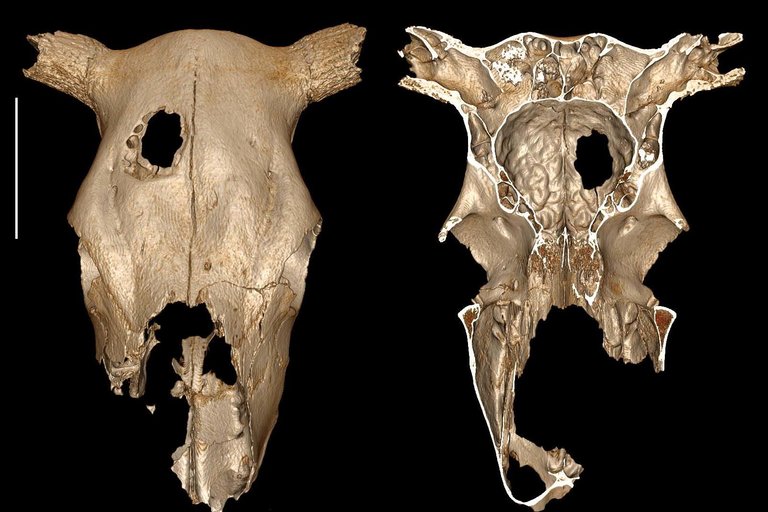

|

| 3D reconstruction of the cow skull showing internally and externally the hole produced by trepanation. Bar corresponds to 10 cm |

While doing archaeological research online, biological anthropologist Alain Froment happened upon a photo of a cow skull in a 1999 paper in a French scientific journal. The 5,000-year-old skull appeared to have a trepanation hole, yet the study concluded that goring from the horn of another animal produced the gash that is about 2.5 inches long and 2 inches wide.

"I was not convinced by the explanation of cow goring," Froment, a researcher at the Museum of Man, located in Paris, told Seeker.

He and Fernando Ramirez Rozzi of the French National Center for Scientific Research analyzed the cow cranium and now believe that the Stone Age animal underwent trepanation. The findings, reported in the journal Scientific Reports, might be the earliest evidence of a veterinary surgery.

Alternatively, the researchers propose that Neolithic people could have practiced human surgical procedures on already dead animals. If so, the almost complete cow skull could provide the earliest known evidence for such an activity.

The fossil originally was found during archaeological excavations carried out from 1975 to 1985 at the Neolithic site of Champ-Durand at Vendée, France. By at least 5,000 years ago, this location near the Atlantic coast served as an important trade center for locals who specialized in salt production and raising livestock.

In addition to cow remains, fossils for pigs, sheep and goats were also unearthed at the site. Many of the bones had either cut marks or were burned — some were cut and burned.

To analyze the cow cranium in detail, Ramirez Rozzi and Froment created 3D reconstructions and studied them with a scanning electron microscope. They determined that the exterior of the hole becomes smaller internally, with borders of the inner and outer regions being irregular and not smooth.

"The traces of scraping are from a stone tool and not a metal one," Froment said.

The researchers instead argue that the almost square shape of the hole, the lack of any marks indicating pressure by an exterior force, and the presence of cut-marks around the hole all suggest that the injury resulted from a surgery. Since there is no evidence for healing, they believe that the procedure was performed on a dead cow, or that the cow did not survive.

The location of the hole interestingly matches where trepanation procedures typically occur on humans.

Froment explained, "This very place on the skull does not cause internal hemorrhage because there is no vein sinus under the bone in that place."

Ramirez Rozzi told Seeker that evidence for trepanation is found all over the world and across multiple time periods. Froment clarified that the most ancient trephined human skull was found in the Ukraine and is dated to about 7,300–6,200 BC. In France, the most ancient trephined human skull is about 7,000 years old, he added.

The researchers previously suspected that a Neolithic wild boar also underwent trepanation, but they could not directly study that particular skull.

Although their paper presents a few different scenarios explaining the bone surgery, both authors favor the idea that Neolithic people practiced surgical procedures on animals before applying them to humans.

Ramirez Rozzi said, "You see a great deal of expertise in human skull trepanation, and the question has always been, 'How could those who carried out these procedures have had the knowledge to do them so perfectly?' They certainly must have practiced before performing surgery on live humans."

Read more at Seeker

Mammal Mass Shrank as Hungry Humans Learned to Hunt

|

| An illustration of a rabbit observing mastodons |

Scientists examining the disappearance of large prehistoric mammals have found evidence that humans and their ancestors drove a sharp reduction in the size of land mammals as hunting skills and weaponry advanced. As a result, the average mammal mass has shrunk more than tenfold over the last 125,000 years, University of New Mexico paleoecologist Felisa Smith told Seeker.

That’s not because species are getting smaller — it’s because the biggest ones went extinct, most likely because they provided the most meat. And that trend has continued into the modern era: Earth’s largest land animal soon may be the domesticated cow, Smith said.

“We used to have animals on the Earth that weighed over 10 tons,” she said. “Now the biggest thing is an elephant that on average is only about three and a half-ish … and if they go extinct, then we’re talking about things no bigger than 900 kilos (2,000 pounds). And that’s maximum size. If you look at mean size, it’s much, much different.”

Smith has studied megafauna extinctions for about 15 years. She and a team from the University of California San Diego, the University of Nebraska, and Stanford University looked back at global fossil records dating back to the start of the Cenozoic Era, after the dinosaurs became extinct. Their findings, published Thursday in the research journal Science lay out a connection between the rise of humans and the shrinking of other mammals over the past 65 million years.

Megafauna like the mastodon, wooly rhinoceros, or the saber-toothed tiger lived on every continent until the Pleistocene epoch, about 125,000 years back, when the human branch of the evolutionary tree spread from Africa to other continents.

North America was rich in large animals, including giant sloths, a bear species that stood as tall as 12 feet, or the glyptodon, an armadillo-like creature “about the size of a Volkswagen Bug,” Smith said.

One finding Smith called surprising was that those trends didn’t appear to be affected by shifts in climate during that period. Animal species tended to adapt by changing their body size, or moving. Meanwhile, it seems people were killers even before we were technically human.

“The only time we see a spike in extinction rates and this huge size bias, where large-bodied things are disproportionately at risk, was where hominids are involved,” she said. “From that, we conclude that it’s probably related to human exploitation of large-bodied animals.”

Evidence of large mammal extinctions appeared as early as the beginning of the Pleistocene in Africa, where human ancestors were evolving alongside them, Smith said. By 40,000 years ago, when today’s Homo sapiens edged out Neanderthals in Eurasia, mammalian body mass dropped about 50 percent. By the end of the Pleistocene, when the last great ice age ebbed, other human ancestors were gone, humans had settled the Americas and long-range weapons like spears and arrows were common — and the average mass of mammals had fallen from nearly 100 kg (220 pounds) to less than eight.

While Smith said climate did not appear to play a role in that process in the past, today may be a different story. With biodiversity facing threats from human encroachment and fossil fuel-driven climate change, the evolutionary escape routes that saved earlier mammal species have been largely closed off, she said.

“Now we’re in a situation where a lot of us are a lot more prosperous than we ever were before, and we have the luxury to say, ‘Oh, we don’t have to use everything to live, now we need to transition to being stewards of the land,’ ” she said.

Read more at Seeker

Apr 19, 2018

Overcoming bias about music takes work

Expectations and biases play a large role in our experiences. This has been demonstrated in studies involving art, wine and even soda. In 2007, Joshua Bell, an internationally acclaimed musician, illustrated the role context plays in our enjoyment of music when he played his Stradivarius violin in a Washington, D.C., subway, and commuters passed by without a second glance.

Researchers at University of Arkansas, Arizona State University and the University of Connecticut studied this phenomenon and recently published their results in Scientific Reports. They found that simply being told that a performer is a professional or a student changes the way the brain responds to music. They also found that overcoming this bias took a deliberate effort.

The study involved 20 participants without formal training in music. Inside a functional magnetic imaging, or fMRI, machine in the newly founded Brain Imaging Research Center at the University of Connecticut, the participants listened to eight pairs of 70-second musical excerpts, presented in a random order. Each pair consisted of two different performances of the same excerpt. The participants were told that one of the pairs was played by a "conservatory student of piano" and the other was a "world-renowned professional pianist." Although participants were actually listening to a student and professional performance, they heard each pair twice during the experiment with the labels reversed, ensuring that the researchers could investigate the effect of the label independent of the qualities of the performance itself.

Participants rated their enjoyment of each excerpt on a scale of one to 10, and they indicated which of the two excerpts in each pair they preferred. The researchers used the fMRI scans to examine regions of the brain that are associated with auditory processing, pleasure and reward, and cognitive control.

In order to study the brain activity associated with bias, the researchers compared brain images of the participants who preferred the "professional" excerpts with images of participants who preferred the "student" excerpts. They found that when a participant preferred the piece attributed to a professional player, there was significantly more activity in the primary auditory cortex, as well as a region of the brain associated with pleasure and reward.

This activity started when the participant was informed that the player was a professional -- before the music even began -- and remained consistent during the excerpt, suggesting that the belief that a musician is a professional caused these participants to pay more attention to the music and biased their listening experience not just at the start, but throughout the excerpt.

The researchers also examined the brain activity of participants who preferred the "student" recordings over the "professional" recordings. While these participants were listening to the recordings attributed to the professional, researchers saw higher activity in a region of the brain related to cognitive control and deliberative thinking throughout the course of the excerpt. They also found that these participants had more connectivity between the parts of their brain related to cognitive control and reward.

"It was different when people listened carefully enough to realize we were fooling them -- that is, when they realized they liked the performance labeled 'student' better," said Edward Large, a theoretical neuroscientist at UConn who made the fMRI available for the study.

"The participants who could resist the bias (who decided they liked the performance primed as student or disliked the one primed as professional) had to recruit regions devoted to executive control -- it looked like work for them to suppress the bias," said Elizabeth Margulis, distinguished professor of music theory and music cognition at the University of Arkansas. "These data demonstrate how critical factors outside the notes themselves, like the information you have about a performer (explicitly in the form of a prime or implicitly in the form of positioning on stage at Carnegie Hall or on a subway platform) can transform what you are able to hear and how you evaluate a musical performance."

Read more at Science Daily

Researchers at University of Arkansas, Arizona State University and the University of Connecticut studied this phenomenon and recently published their results in Scientific Reports. They found that simply being told that a performer is a professional or a student changes the way the brain responds to music. They also found that overcoming this bias took a deliberate effort.

The study involved 20 participants without formal training in music. Inside a functional magnetic imaging, or fMRI, machine in the newly founded Brain Imaging Research Center at the University of Connecticut, the participants listened to eight pairs of 70-second musical excerpts, presented in a random order. Each pair consisted of two different performances of the same excerpt. The participants were told that one of the pairs was played by a "conservatory student of piano" and the other was a "world-renowned professional pianist." Although participants were actually listening to a student and professional performance, they heard each pair twice during the experiment with the labels reversed, ensuring that the researchers could investigate the effect of the label independent of the qualities of the performance itself.

Participants rated their enjoyment of each excerpt on a scale of one to 10, and they indicated which of the two excerpts in each pair they preferred. The researchers used the fMRI scans to examine regions of the brain that are associated with auditory processing, pleasure and reward, and cognitive control.

In order to study the brain activity associated with bias, the researchers compared brain images of the participants who preferred the "professional" excerpts with images of participants who preferred the "student" excerpts. They found that when a participant preferred the piece attributed to a professional player, there was significantly more activity in the primary auditory cortex, as well as a region of the brain associated with pleasure and reward.

This activity started when the participant was informed that the player was a professional -- before the music even began -- and remained consistent during the excerpt, suggesting that the belief that a musician is a professional caused these participants to pay more attention to the music and biased their listening experience not just at the start, but throughout the excerpt.

The researchers also examined the brain activity of participants who preferred the "student" recordings over the "professional" recordings. While these participants were listening to the recordings attributed to the professional, researchers saw higher activity in a region of the brain related to cognitive control and deliberative thinking throughout the course of the excerpt. They also found that these participants had more connectivity between the parts of their brain related to cognitive control and reward.

"It was different when people listened carefully enough to realize we were fooling them -- that is, when they realized they liked the performance labeled 'student' better," said Edward Large, a theoretical neuroscientist at UConn who made the fMRI available for the study.

"The participants who could resist the bias (who decided they liked the performance primed as student or disliked the one primed as professional) had to recruit regions devoted to executive control -- it looked like work for them to suppress the bias," said Elizabeth Margulis, distinguished professor of music theory and music cognition at the University of Arkansas. "These data demonstrate how critical factors outside the notes themselves, like the information you have about a performer (explicitly in the form of a prime or implicitly in the form of positioning on stage at Carnegie Hall or on a subway platform) can transform what you are able to hear and how you evaluate a musical performance."

Read more at Science Daily

Study reveals new Antarctic process contributing to sea level rise and climate change

|

| This is the Mertz Glacier in January 2017. |

Led by IMAS PhD student Alessandro Silvano and published in the journal Science Advances, the research found that glacial meltwater makes the ocean's surface layer less salty and more buoyant, preventing deep mixing in winter and allowing warm water at depth to retain its heat and further melt glaciers from below.

"This process is similar to what happens when you put oil and water in a container, with the oil floating on top because it's lighter and less dense," Mr Silvano said.

"The same happens near Antarctica with fresh glacial meltwater, which stays above the warmer and saltier ocean water, insulating the warm water from the cold Antarctic atmosphere and allowing it to cause further glacial melting.

"We found that in this way increased glacial meltwater can cause a positive feedback, driving further melt of ice shelves and hence an increase in sea level rise."

The study found that fresh meltwater also reduces the formation and sinking of dense water in some regions around Antarctica, slowing ocean circulation which takes up and stores heat and carbon dioxide.

"The cold glacial meltwaters flowing from the Antarctic cause a slowing of the currents which enable the ocean to draw down carbon dioxide and heat from the atmosphere.

"In combination, the two processes we identified feed off each other to further accelerate climate change."

Mr Silvano said a similar mechanism has been proposed to explain rapid sea level rise of up to five metres per century at the end of the last glacial period around 15,000 years ago.

"Our study shows that this feedback process is not only possible but is in fact already underway, and may drive further acceleration of the rate of sea level rise in the future.

"Currently the ice shelves resist the flow of ice to the ocean, acting like a buttress to hold the ice sheet on the Antarctic continent.

"Where warm ocean waters flow under the ice shelves they can drive rapid melting from below, causing ice shelves to thin or break up and reducing the buttressing effect.

"This process leads to rising sea levels as more ice flows to the ocean.

"Our results suggest that a further increase in the supply of glacial meltwater to the waters around the Antarctic shelf may trigger a transition from a cold regime to a warm regime, characterised by high rates of melting from the base of ice shelves and reduced formation of cold bottom waters that support ocean uptake of atmospheric heat and carbon dioxide," Mr Silvano said.

From Science Daily

New ancestor of modern sea turtles found in Alabama

|

| This is a reconstruction of the new species (Peritresius martini). |

Modern day sea turtles were previously thought to have had a single ancestor of the of the Peritresius clade during the Late Cretaceous epoch, from about 100 to 66 million years ago. This ancestral species, Peritresius ornatus, lived exclusively in North America, but few Peritresius fossils from this epoch had been found in what is now the southeastern U.S., an area known for producing large numbers of Late Cretaceous marine turtle fossils. In this study, the research team analyzed sea turtle fossils collected from marine sediments in Alabama and Mississippi, dating from about 83 to 66 million years ago.

The researchers identified some of the Alabama fossils as representing a new Peritresius species, which they named Peritresius martini after Mr. George Martin who discovered the fossils. Their identification was based on anatomical features including the shape of the turtle's shell. Comparing P. martini and P. ornatus, the researchers noted that the shell of P. ornatus is unusual amongst Cretaceous sea turtles in having sculptured skin elements which are well-supplied with blood vessels. This unique feature may suggest that P. ornatus was capable of thermoregulation, which could have enabled Peritresius to keep warm and survive during the cooling period of the Cretaceous, unlike many other marine turtles that went extinct.

These findings extend the known evolutionary history for thePeritresius clade to include two anatomically distinct species from the Late Cretaceous epoch, and also reveal that Peritresius was distributed across a wider region than previously thought.

Drew Gentry says: "This discovery not only answers several important questions about the distribution and diversity of sea turtles during this period but also provides further evidence that Alabama is one of the best places in the world to study some of the earliest ancestors of modern sea turtles."

From Science Daily

Martian moons model indicates formation following large impact

The origin of the Red Planet's small moons has been debated for decades. The question is whether the bodies were asteroids captured intact by Mars gravity or whether the tiny satellites formed from an equatorial disk of debris, as is most consistent with their nearly circular and co-planar orbits. The production of a disk by an impact with Mars seemed promising, but prior models of this process were limited by low numerical resolution and overly simplified modeling techniques.

"Ours is the first self-consistent model to identify the type of impact needed to lead to the formation of Mars' two small moons," said lead author Dr. Robin Canup, an associate vice president in the SwRI Space Science and Engineering Division. Canup is one of the leading scientists using large-scale hydrodynamical simulations to model planet-scale collisions, including the prevailing Earth-Moon formation model.

"A key result of the new work is the size of the impactor; we find that a large impactor -- similar in size to the largest asteroids Vesta and Ceres -- is needed, rather than a giant impactor," Canup said. "The model also predicts that the two moons are derived primarily from material originating in Mars, so their bulk compositions should be similar to that of Mars for most elements. However, heating of the ejecta and the low escape velocity from Mars suggests that water vapor would have been lost, implying that the moons will be dry if they formed by impact."

The new Mars model invokes a much smaller impactor than considered previously. Our Moon may have formed when a Mars-sized object crashed into the nascent Earth 4.5 billion years ago, and the resulting debris coalesced into the Earth-Moon system. The Earth's diameter is about 8,000 miles, while Mars' diameter is just over 4,200 miles. The Moon is just over 2,100 miles in diameter, about one-fourth the size of Earth.

While they formed in the same timeframe, Deimos and Phobos are very small, with diameters of only 7.5 miles and 14 miles respectively, and orbit very close to Mars. The proposed Phobos-Deimos forming impactor would be between the size of the asteroid Vesta, which has a diameter of 326 miles, and the dwarf planet Ceres, which is 587 miles wide.

"We used state-of-the-art models to show that a Vesta-to-Ceres-sized impactor can produce a disk consistent with the formation of Mars' small moons," said the paper's second author, Dr. Julien Salmon, an SwRI research scientist. "The outer portions of the disk accumulate into Phobos and Deimos, while the inner portions of the disk accumulate into larger moons that eventually spiral inward and are assimilated into Mars. Larger impacts advocated in prior works produce massive disks and more massive inner moons that prevent the survival of tiny moons like Phobos and Deimos."

These findings are important for the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) Mars Moons eXploration (MMX) mission, which is planned to launch in 2024 and will include a NASA-provided instrument. The MMX spacecraft will visit the two Martian moons, land on the surface of Phobos and collect a surface sample to be returned to Earth in 2029.

Read more at Science Daily

Natural selection gave a freediving people in Southeast Asia bigger spleens

|

| This image shows a Bajau diver hunting fish underwater using a traditional spear. |

"Humans are pretty plastic beings. We can adapt to a number of different extreme environments just through our lifestyle changes or our behavioral changes, so it wasn't necessarily likely that we would find an actual genetic adaptation to diving," says first author Melissa Ilardo, a doctoral student at the University of Copenhagen working with co-senior researchers Rasmus Nielsen (@ras_nielsen) of the University of California, Berkeley, and Eske Willerslev of the University of Copenhagen and the University of Cambridge. "The first sign that we were maybe onto something was when we saw that both the Bajau divers and non-divers had larger spleens than the Saluan, a nearby, non-diving population."

Spleen size is significant because of the organ's role in the human dive response, which occurs when our faces are submerged in water and we hold our breath. As our heart rate slows and blood vessels in our extremities constrict, the spleen contracts, releasing oxygenated red blood cells and making more oxygen available in the bloodstream. A larger spleen means that more oxygen gets released. Perhaps for this reason, large spleens have also been documented in diving seals.

The Bajau having larger spleens than their non-diving neighbors suggested that their diving culture had shaped their physiology. But the fact that non-divers and divers both had larger spleens suggested that it wasn't just a plastic response to spending so much time under water. There was likely something different about the Sea Nomads' DNA.

When the researchers scanned the genomes of the Bajau, they identified 25 sites that differed significantly from two comparison populations, the Saluan and the Han Chinese. Of these, one site on a gene known as PDE10A was found to be correlated with the Bajau's larger spleen size, even after accounting for confounding factors like age, sex, and height. In mice, PDE10A is known for regulating a thyroid hormone that controls spleen size, lending support for the idea that the Bajau might have evolved the spleen size necessary to sustain their long and frequent dives.

"The chance of finding evidence of population-specific natural selection, even in a population as extreme as the Bajau, was pretty slim. It was very exciting to find, and it just opens up so many possibilities," says Ilardo.

Understanding how the human body responds to a lack of oxygen, for instance, is important in a lot of medical contexts, from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to surgery. Hypoxia has been well studied in populations living at high altitudes, where the lack of oxygen is much more chronic. But not as much research has been done on diving populations. "Here it's more of an acute hypoxia, almost similar to what's experienced with sleep apnea," she says. By making their data freely available to other researchers, she and her co-authors hope that some of what they've learned from the Bajau can be applied in medical contexts.

For the Bajau, Ilardo believes that the decision to participate in this research is about better understanding themselves. "I basically just showed up at the house of the chief of the village, this bizarre, foreign girl with an ultrasound machine asking about spleens," she says. "They're the most welcoming people I've ever met, but I wanted to make sure that they understood the science behind what I was doing, so that it wasn't just me taking measurements from them without giving back. And we do have a trip planned to return to the community to explain the results to them."

"They're explorers, so I think they're inherently curious and want to know more about the world, including about their own biology," she says.

Read more at Science Daily

Apr 18, 2018

Marine fish won an evolutionary lottery 66 million years ago

|

| An evolutionary history of major groups of acanthomorphs, an extremely diverse group of fish. |

Slightly more than half of today's fish are "marine fish," meaning they live in oceans. And most marine fish, including tuna, halibut, grouper, sea horses and mahi-mahi, belong to an extraordinarily diverse group called acanthomorphs. (The study did not analyze the large numbers of other fish that live in lakes, rivers, streams, ponds and tropical rainforests.)

The aftermath of the asteroid crash created an enormous evolutionary void, providing an opportunity for the marine fish that survived it to greatly diversify.

"Today's rich biodiversity among marine fish shows the fingerprints of the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period," said Michael Alfaro, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology in the UCLA College and lead author of the study.

To analyze those fingerprints, the "evolutionary detectives" employed a new genomics research technique developed by one of the authors. Their work is published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

When they studied the timing of the acanthomorphs' diversification, Alfaro and his colleagues discovered an intriguing pattern: Although there were many other surviving lineages of acanthomorphs, the six most species-rich groups of acanthomorphs today all showed evidence of substantial evolutionary change and proliferation around the time of the mass extinction. Those six groups have gone on to produce almost all of the marine fish diversity that we see today, Alfaro said.

He added that it's unclear why the other acanthomorph lineages failed to diversify as much after the mass extinction.

"The mass extinction, we argue, provided an evolutionary opportunity for a select few of the surviving acanthomorphs to greatly diversify, and it left a large imprint on the biodiversity of marine fishes today," Alfaro said. "It's like there was a lottery 66 million years ago, and these six major acanthomorph groups were the winners."

The findings also closely match fossil evidence of acanthomorphs' evolution, which also shows a sharp rise in their anatomical diversity after the extinction.

The genomic technique used in the study, called sequence capture of DNA ultra-conserved elements, was developed at UCLA by Brant Faircloth, who is now an assistant professor of biological sciences at Louisiana State University. Where previous methods used just 10 to 20 genes to create an evolutionary history, Faircloth's approach creates a more complete and accurate picture by using more than 1,000 genetic markers. (The markers include genes and other DNA components, such as parts of the DNA that turn proteins on or off, and cellular components that play a role in regulating genes.)

The researchers also extracted DNA from 118 species of marine fish and conducted a computational analysis to determine the relationships among them. Among their findings: It's not possible to tell which species are genetically related simply by looking at them. Seahorses, for example, look nothing like goatfish, but the two species are evolutionary cousins -- a finding that surprised the scientists.

Read more at Science Daily

340,000 stars' DNA interrogated in search for sun's lost siblings

|

| A schematic of the HERMES instrument showing the light path of how star light from the telescope AAT is split into four different channels. |

This is a major announcement from an ambitious Galactic Archaeology survey, called GALAH, launched in late 2013 as part of a quest to uncover the formulation and evolution of galaxies. When complete, GALAH will investigate more than a million stars.

The GALAH survey used the HERMES spectrograph at the Australian Astronomical Observatory's (AAO) 3.9-metre Anglo-Australian Telescope near Coonabarabran, NSW, to collect spectra for the 340,000 stars.

The GALAH Survey today makes its first major public data release.

The 'DNA' collected traces the ancestry of stars, showing astronomers how the Universe went from having only hydrogen and helium -- just after the Big Bang -- to being filled today with all the elements we have here on Earth that are necessary for life.

"No other survey has been able to measure as many elements for as many stars as GALAH," said Dr Gayandhi De Silva, of the University of Sydney and AAO, the HERMES instrument scientist who oversaw the groups working on today's major data release.

"This data will enable such discoveries as the original star clusters of the Galaxy, including the Sun's birth cluster and solar siblings -- there is no other dataset like this ever collected anywhere else in the world," Dr De Silva said.

Dr. Sarah Martell from the UNSW Sydney, who leads GALAH survey observations, explained that the Sun, like all stars, was born in a group or cluster of thousands of stars.

"Every star in that cluster will have the same chemical composition, or DNA -- these clusters are quickly pulled apart by our Milky Way Galaxy and are now scattered across the sky," Dr Martell said.

"The GALAH team's aim is to make DNA matches between stars to find their long-lost sisters and brothers."

For each star, this DNA is the amount they contain of each of nearly two dozen chemical elements such as oxygen, aluminium, and iron.

Unfortunately, astronomers cannot collect the DNA of a star with a mouth swab but instead use the starlight, with a technique called spectroscopy.