Feb 24, 2018

Metalens combined with an artificial muscle

The research is published in Science Advances.

"This research combines breakthroughs in artificial muscle technology with metalens technology to create a tunable metalens that can change its focus in real time, just like the human eye," said Alan She, a graduate student at SEAS and first author of the paper. "We go one step further to build the capability of dynamically correcting for aberrations such as astigmatism and image shift, which the human eye cannot naturally do."

"This demonstrates the feasibility of embedded optical zoom and autofocus for a wide range of applications including cell phone cameras, eyeglasses and virtual and augmented reality hardware," said Federico Capasso, Robert L. Wallace Professor of Applied Physics and Vinton Hayes Senior Research Fellow in Electrical Engineering at SEAS and senior author of the paper. "It also shows the possibility of future optical microscopes, which operate fully electronically and can correct many aberrations simultaneously."

The Harvard Office of Technology Development has protected the intellectual property relating to this project and is exploring commercialization opportunities.

To build the artificial eye, the researchers first needed to scale-up the metalens.

Prior metalenses were about the size of a single piece of glitter. They focus light and eliminate spherical aberrations through a dense pattern of nanostructures, each smaller than a wavelength of light.

"Because the nanostructures are so small, the density of information in each lens is incredibly high," said She. "If you go from a 100 micron-sized lens to a centimeter sized lens, you will have increased the information required to describe the lens by ten thousand. Whenever we tried to scale-up the lens, the file size of the design alone would balloon up to gigabytes or even terabytes."

To solve this problem, the researchers developed a new algorithm to shrink the file size to make the metalens compatible with the technology currently used to fabricate integrated circuits. In a paper recently published in Optics Express, the researchers demonstrated the design and fabrication of metalenses up to centimeters or more in diameter.

"This research provides the possibility of unifying two industries: semiconductor manufacturing and lens-making, whereby the same technology used to make computer chips will be used to make metasurface-based optical components, such as lenses," said Capasso.

Next, the researchers needed to adhere the large metalens to an artificial muscle without compromising its ability to focus light. In the human eye, the lens is surrounded by ciliary muscle, which stretches or compresses the lens, changing its shape to adjust its focal length. Capasso and his team collaborated with David Clarke, Extended Tarr Family Professor of Materials at SEAS and a pioneer in the field of engineering applications of dielectric elastomer actuators, also known as artificial muscles.

The researchers chose a thin, transparent dielectic elastomer with low loss -- meaning light travels through the material with little scattering -- to attach to the lens. To do so, they needed to developed a platform to transfer and adhere the lens to the soft surface.

"Elastomers are so different in almost every way from semiconductors that the challenge has been how to marry their attributes to create a novel multi-functional device and, especially how to devise a manufacturing route," said Clarke. "As someone who worked on one of the first scanning electron microscopes (SEMs) in the mid 1960's, it is exhilarating to be a part of creating an optical microscope with the capabilities of an SEM, such as real-time aberration control."

The elastomer is controlled by applying voltage. As it stretches, the position of nanopillars on the surface of the lens shift. The metalens can be tuned by controlling both the position of the pillars in relation to their neighbors and the total displacement of the structures. The researchers also demonstrated that the lens can simultaneously focus, control aberrations caused by astigmatisms, as well as perform image shift.

Together, the lens and muscle are only 30 microns thick.

"All optical systems with multiple components -- from cameras to microscopes and telescopes -- have slight misalignments or mechanical stresses on their components, depending on the way they were built and their current environment, that will always cause small amounts of astigmatism and other aberrations, which could be corrected by an adaptive optical element," said She. "Because the adaptive metalens is flat, you can correct those aberrations and integrate different optical capabilities onto a single plane of control."

Next, the researchers aim to further improve the functionality of the lens and decrease the voltage required to control it.

Read more at Science Daily

Researchers Recreate Clay Minerals Found on Mars

|

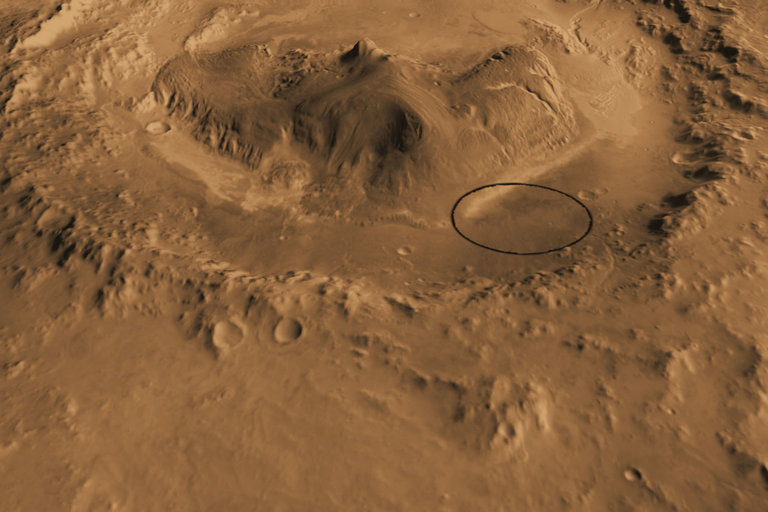

| This computer-generated view, based on multiple orbital observations, shows Mars's Gale crater as if seen from an aircraft north of the crater. |

It was thought that the iron and magnesium-rich clay minerals in Gale Crater — which has also provided evidence of a long-term presence of liquid water in Mars’ past — would be a good place for organic matter to be preserved, as well.

But it turns out, according to a new study by a team of geoscientists at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, certain features of the clay minerals on Mars may not be conducive to the preservation of organic matter after all.

“We were able to show that the clay minerals formed from oxidized iron, rather than the reduced iron that had previously been thought,” lead author Elizabeth Hausrath said in an email to Seeker. “This suggests that if organic matter were present in the past on Mars, it might not be preserved to be detected today. So this might help explain why larger concentrations of organic matter haven't been detected on Mars, at least not yet!”

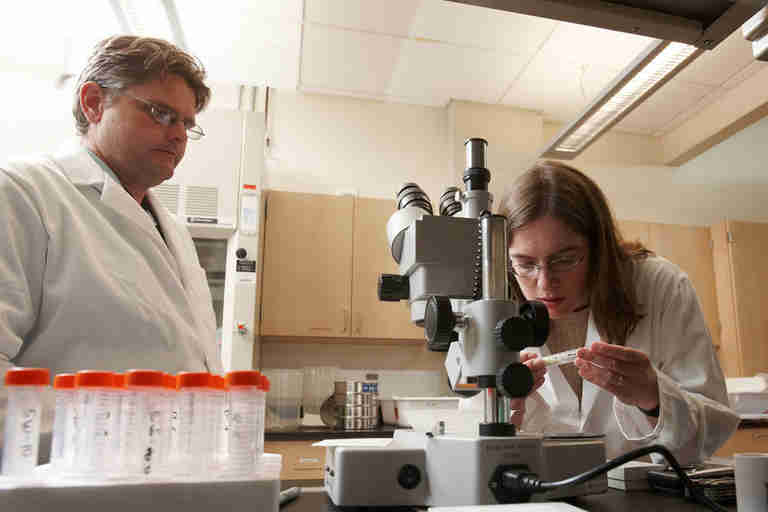

|

| UNLV Researcher Libby Hausrath works with student Seth Grainey in her lab. |

From previous experiments, it was thought that anoxic conditions — an environment without oxygen — were required for iron-magnesium clay minerals to form. On Earth, a hydrothermal vent would be an example of an anoxic environment. These vents are home to mostly microbes, and oxygen is actually toxic to most of them. Therefore, since thousands of locations on Mars have rock units containing iron-magnesium minerals it was thought any organics would be well preserved.

But Hausrath and colleagues were also able to synthesize clay minerals under oxidized conditions — where oxygen was present — which would destroy organic molecules. What they found is that these types of minerals actually formed faster when oxygen was present.

“The results suggested that the iron and magnesium-rich clay minerals formed quickly under oxidized conditions, which could help explain low concentrations of organics within some rocks or sediments on Mars,” former Ph.D. student Seth Gainey said in a statement.

Therefore, past organic matter, including possible signs of life, may not be well-preserved on Mars. But that doesn’t mean that life never formed on Mars. As we know on Earth, life seems to adapt to the conditions in which it was formed, and life on Mars may have perhaps developed to adapt to the oxidized conditions in the soil.

“Terrestrial life has certainly adapted to very challenging conditions,” Hausrath said. “For example, we have recently published work on how snow algae, which grow to very high concentrations in very challenging low nutrient snowy environments, are able to use minerals as nutrient sources. So certainly what we know of life from Earth is that it seems to be very able to adapt to challenging circumstances.”

The study Hausrath mention was published last month in the journal of the American Society for Microbiology. Her lab's latest findings were published in the journal Nature.

From all the evidence gathered by the Curiosity rover, scientists think Gale Crater was once the site of a lake billions of years ago, and rocks like mudstone formed from sediment in the lake. While organics were found there, there is not enough evidence to tell if the matter found by the rover team came from ancient Martian life or from a non-biological process. Some examples of non-biological sources include chemical reactions in water at ancient Martian hot springs or delivery of organic material to Mars by interplanetary dust or fragments of asteroids and comets.

But the discovery of organics shows that the ancient Martian environment offered a supply of organic molecules for use as building blocks for life and an energy source for life. Curiosity's earlier analysis of this same mudstone revealed that the environment offered water and chemical elements essential for life and a different chemical energy source.

Read more at Seeker

Feb 23, 2018

On second thought, the Moon's water may be widespread and immobile

|

| If the Moon has enough water, and if it's reasonably convenient to access, future explorers might be able to use it as a resource. |

The findings could help researchers understand the origin of the Moon's water and how easy it would be to use as a resource. If the Moon has enough water, and if it's reasonably convenient to access, future explorers might be able to use it as drinking water or to convert it into hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel or oxygen to breathe.

"We find that it doesn't matter what time of day or which latitude we look at, the signal indicating water always seems to be present," said Joshua Bandfield, a senior research scientist with the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado, and lead author of the new study published in Nature Geoscience. "The presence of water doesn't appear to depend on the composition of the surface, and the water sticks around."

The results contradict some earlier studies, which had suggested that more water was detected at the Moon's polar latitudes and that the strength of the water signal waxes and wanes according to the lunar day (29.5 Earth days). Taking these together, some researchers proposed that water molecules can "hop" across the lunar surface until they enter cold traps in the dark reaches of craters near the north and south poles. In planetary science, a cold trap is a region that's so cold, the water vapor and other volatiles which come into contact with the surface will remain stable for an extended period of time, perhaps up to several billion years.

The debates continue because of the subtleties of how the detection has been achieved so far. The main evidence has come from remote-sensing instruments that measured the strength of sunlight reflected off the lunar surface. When water is present, instruments like these pick up a spectral fingerprint at wavelengths near 3 micrometers, which lies beyond visible light and in the realm of infrared radiation.

But the surface of the Moon also can get hot enough to "glow," or emit its own light, in the infrared region of the spectrum. The challenge is to disentangle this mixture of reflected and emitted light. To tease the two apart, researchers need to have very accurate temperature information.

Bandfield and colleagues came up with a new way to incorporate temperature information, creating a detailed model from measurements made by the Diviner instrument on NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, or LRO. The team applied this temperature model to data gathered earlier by the Moon Mineralogy Mapper, a visible and infrared spectrometer that NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, provided for India's Chandrayaan-1 orbiter.

The new finding of widespread and relatively immobile water suggests that it may be present primarily as OH, a more reactive relative of H2O that is made of one oxygen atom and one hydrogen atom. OH, also called hydroxyl, doesn't stay on its own for long, preferring to attack molecules or attach itself chemically to them. Hydroxyl would therefore have to be extracted from minerals in order to be used.

The research also suggests that any H2O present on the Moon isn't loosely attached to the surface.

"By putting some limits on how mobile the water or the OH on the surface is, we can help constrain how much water could reach the cold traps in the polar regions," said Michael Poston of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas.

Sorting out what happens on the Moon could also help researchers understand the sources of water and its long-term storage on other rocky bodies throughout the solar system.

The researchers are still discussing what the findings tell them about the source of the Moon's water. The results point toward OH and/or H2O being created by the solar wind hitting the lunar surface, though the team didn't rule out that OH and/or H2O could come from the Moon itself, slowly released from deep inside minerals where it has been locked since the Moon was formed.

Read more at Science Daily

Surprising new study redraws family tree of domesticated and 'wild' horses

|

| This is a modern Przewalksi horse. |

Research published in Science today overturns a long-held assumption that Przewalski's horses, native to the Eurasian steppes, are the last wild horse species on Earth. Instead, phylogenetic analysis shows Przewalski's horses are feral, descended from the earliest-known instance of horse domestication by the Botai people of northern Kazakhstan some 5,500 years ago.

Further, the new paper finds that modern domesticated horses didn't descend from the Botai horses, an assumption previously held by many scientists.

"This was a big surprise," said co-author Sandra Olsen, curator-in-charge of the archaeology division of the Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum at the University of Kansas, who led archaeological work at known Botai villages. "I was confident soon after we started excavating Botai sites in 1993 that we had found the earliest domesticated horses. We went about trying to prove it, but based on DNA results Botai horses didn't give rise to today's modern domesticated horses -- they gave rise to the Przewalski's horse."

The findings signify there are no longer true "wild" horses left, only feral horses that descend from horses once domesticated by humans, including Przewalski's horses and mustangs that descend from horses brought to North America by the Spanish.

"This means there are no living wild horses on Earth -- that's the sad part," said Olsen. "There are a lot of equine biologists who have been studying Przewalskis, and this will be a big shock to them. They thought they were studying the last wild horses. It's not a real loss of biodiversity -- but in our minds, it is. We thought there was one last wild species, and we're only just now aware that all wild horses went extinct."

Many of the horse bones and teeth Olsen excavated at two Botai sites in Kazakhstan, called Botai and Krasnyi Yar, were used in the phylogenetic analysis. The international team of researchers behind the paper sequenced the genomes of 20 horses from the Botai and 22 horses from across Eurasia that spanned the last 5,500 years. They compared these ancient horse genomes with already published genomes of 18 ancient and 28 modern horses.

"Phylogenetic reconstruction confirmed that domestic horses do not form a single monophyletic group as expected if descending from Botai," the authors wrote. "Earliest herded horses were the ancestors of feral Przewalski's horses but not of modern domesticates."

Olsen said the findings give rise to a new scientific quest: locating the real origins of today's domesticated horses.

"What's interesting is that we have two different domestication events from slightly different species, or separate sub-species," she said. (The Przewalski's horse's taxonomic position is still debated.) "It's thought that modern-day domesticated horses came from Equus ferus, the extinct European wild horse. The problem is they were thought to have existed until the early 1900s. But, the remains of two individuals in St. Petersburg, Russia, are probably feral, too, or at least probably had some domesticated genes."

Olsen began excavating Botai village sites in Kazakhstan in 1993 after the fall of the Soviet Union made the region accessible to western scientists. Some of the horse remains collected by Olsen were tested as part of the new study showing their ancestry of modern-day Przewalskis.

The Botai's ancestors were nomadic hunters until they became the first-known culture to domesticate horses around 5,500 years ago, using horses for meat, milk, work and likely transportation.

"Once they domesticated horses they became sedentary, with large villages of up to 150 or more houses," said Olsen, who specializes in zooarchaeology, or the study of animal remains from ancient human occupation sites. "They lived primarily on horse meat, and they had no agriculture. We had several lines of evidence that supported domestication. The fact the Botai were sedentary must have meant they had domesticated animals, or plants, which they didn't have. More than 95 percent of the bones from the Botai sites were from horses -- they were in a sense mono-cropping one species with an incredible focus. If they were hunting horses on foot, they would have quickly depleted bands of horses in the vicinity of the villages and would have had to go farther afield to hunt -- it wouldn't have been feasible or supported that large human population."

The KU researcher also cited bone artifacts from Botai sites used to make rawhide thongs that might have been fashioned into bridles, lassos, whips, riding crops and hobbles, as further evidence of horse domestication. Moreover, the Botai village sites include horse corrals.

"We found a corral that contained high levels of nitrogen and sodium from manure and urine," said Olsen. "It was very concentrated within that corral. The final smoking gun was finding residues of mares' milk in the pottery. It's commonplace today in Mongolia and Kazakhstan to milk horses -- when it's fermented it has considerable nutritional value and is very high in vitamins."

Interestingly, Olsen found that after slaughtering horses, the Botai buried some horse skulls and necks in pits with their snouts facing the southeast, toward where the sun rose in the morning in autumn. Mongols and Kazakhs slaughter most of their horses at that time of year because that is when they retain the most amount of nutritious fat in their bodies.

"It's interesting because throughout the Indo-European diaspora there's a strong connection between the sun god and the horse," she said. "It may be that Botai people spoke an early proto-Indo-European language, and they also connected the horse to the sun god. Later in time, and this idea is in the historical record for the Indo-European diaspora, it was believed the sun god was born in the east and rode across the sky in a chariot, pulled by white horses. According to the belief, he would then die in the west and be reborn every day."

The team behind the paper believe Przewalski's horses likely escaped from domestic Botai herds in eastern Kazakhstan or western Mongolia.

"They started developing a semi-wild lifestyle like our mustangs, but they still have a wild appearance," Olsen said. "This is partly why biologists assumed they were genuinely wild animals. They have an upright mane, something associated with wild equids. They also have a dun coat, like the ones you see in the Ice Age cave paintings in France and Spain made when horses were wild. Their size, however, is very similar to what you see at Botai and other sites."

By 1969, Przewalski's horses were declared extinct in the wild, and all living today originated from just 15 individuals captured around 1900. Today, there are approximately 2,000 Przewalski's horses, all descended from those captured horses, and they have been reintroduced on the Eurasian steppes. In a sense, the horses have fared better than the peoples who once domesticated them.

Read more at Science Daily

Neanderthals Painted the World’s Oldest Cave Art

These admirers were wrong, however, according to new research that concludes Neanderthals created the images, whose ages now make them the world's first known cave art. Some of the paintings date to at least 64,800 years ago, according to a paper published in the journal Science — and they are probably much older.

The prior record-holder for oldest cave art is a painting of a pig at Timpuseng cave in Sulawesi, Indonesia. It was dated to a minimum age of 35,400 years old.

"Cave art is amazing in all its forms," lead author Dirk Hoffmann of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology's Department of Human Evolution told Seeker. "I never had any expectations about how old cave art is or who made it. I simply wanted to contribute to obtaining a robust chronology for cave art. It is certainly impressive to find out that some of the art is older than 64,000 years and still exists on cave walls."

|

| Dirk Hoffmann and Alistair Pike sampling calcite from a calcite crust on top of the red scalariform sign in La Pasiega |

The international team of researchers from Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Spain utilized a clever method, U-Th dating, to date the art at three sites: La Pasiega in northeastern Spain, Maltravieso in western Spain, and Ardales in southern Spain. The dating technique is based on the radioactive decay of uranium into thorium. It can determine ages up to 500,000 years ago.

Cave art often tends to be covered by carbonate deposits, which form via water precipitating out of the underlying rock over the millennia. These deposits contain traces of the radioactive elements of uranium and thorium.

U-Th dating has been around for years, but it initially required large samples of the carbonate material. Pike explained that he and others faced this challenge in 2003, when using the method to analyze cave art in Creswell Crags, which is located in Derbyshire, England.

Hoffmann, employing state of the art mass spectrometers, improved on the U-Th dating method: Now only a few milligrams of carbonate material are needed. This eliminates the risk of damaging the priceless artwork underneath.

Taking more than 60 samples, the researchers determined that, at minimum, the Spanish cave art was created around 64,800 years ago — 20,000 years before fossil evidence shows anatomically modern humans were in Europe.

"The paintings could be much older," co-author Joao Zilhão of the Catalan Institute for Research and Advanced Studies told Seeker.

He added that stone circles in Bruniquel Cave, southwest France, date to around 175,000 years ago, "which shows that people — in this case Neanderthals — were going underground, 300 meters (984.3 feet) from a cave entrance, to so stuff that required planning, time, lighting, etc., and what for? Were they the first people going into caves for sports? I don't know about others, but I find that hard to believe."

|

| Perforated shells found in sediments in Cueva de los Aviones and date to between 115,000 and 120,000 years |

Early symbolic artifacts from Africa date to about 92,000 years ago.

Given the age of the Spanish decorated shells, again preceding fossil evidence for humans in the region, the evidence suggests that Neanderthals decorated the shells and possessed symbolic material culture. This refers to a collection of cultural and intellectual achievements handed down from generation to generation. So far, it has only been attributed to our own species, Homo sapiens.

Zilhão believes that Neanderthals are actually members of Homo sapiens. This possibility has been debated for decades, with some anthropologists believing that Neanderthals represent an entirely different species, others holding that they are a subspecies of Homo sapiens, and still others referring to them as members of our species, but representing a more archaic form.

If future studies support that Neanderthals did indeed have symbolic material culture, then there are additional important implications.

"Our results show that they were making deliberate decisions about what to create on cave walls," co-author Paul Pettitt of Durham University told Seeker. "Their art was an extension of the body; they used their hands directly to color stalactites at Ardales, to create negative stencils at Maltravieso and to create rectilinear designs with their fingertips at La Pasiega. This probably derived from the decoration — perhaps symbolically — of their bodies, but the interesting issue is why they were extending their body symbolism to cave walls."

"It is difficult not to invoke some kind of ritual behavior from this," Pettitt continued. "Why otherwise take risks for a behavior that has no immediate or obvious benefit to survival?"

By risks, he was referring to the inherent dangers of climbing into dark caves, where fossils for toothy mammal predators have been found and accidents could easily happen.

The first appearances of Neanderthals and "modern" humans in the fossil record predates their known artistic creations, which shows that they probably developed the skills over time. It is possible that each group did this independently. Studies on non-human primates show that individuals are capable of innovation, which can be learned by watching others.

It is thought, for example, that a clever capuchin monkey devised a new, effective way to crack nuts, by using a rock and a log like a hammer and anvil. Now many capuchins are cracking cashews and other nuts this way.

A particularly innovative Neanderthal or anatomically modern human could have invented painting — whether on the body, on shells, or cave walls — with the ability passed down to others.

|

| Cueva de los Aviones, seen from the breakwater of Cartagena harbor |

The related cognitive hardwiring could even go back to 1.5 million years ago, when fossils suggest that humans were evolving larger brains than their primate ancestors.

"That material culture, archaeologically visible manifestations, only appears after 200,000 years ago probably means that it is at a time when individual and social interactions became so complex that conventions, signs, and symbols became necessary for the transmission of information about status, territory, ethnicity, rights over the resources of land, etc.," Zilhão explained.

Israel Hershkovitz, an expert on early human evolution at Tel Aviv University, notes that the dates of the Spanish cave art coincide with an extensive modern human migration out of Africa. Hershkovitz, who did not work on the new studies, told Seeker, "Members of this group could have reached the Iberian Peninsula through the Gibraltar Straight."

He added, "I am aware that, for the time being, fossil evidence for modern humans (in Spain) is dated to less than 45,000 years ago, but this is for the time being. I would not be surprised if they were there much earlier."

On the other hand, he said that he "would not be surprised" if the cave art and decorated shells were produced by Neanderthals.

"Why not?" he asked. "After all, Neanderthals and modern humans share the same tool technology, and by judging from tool assemblages alone there is no way to know whether a given site was inhabited by Neanderthals or modern humans."

Hoffmann and his team faced somewhat similar challenges in teasing apart the ancient from the more recent paintings in the Spanish caves.

"You need to think about cave walls the same way as you would about the walls of a medieval church," Zilhão explained. "They were painted and repainted over the ages, so it is entirely possible that paintings made 60,000, 40,000, 20,000, or 10,000 years ago co-exist on the same surface, even on the same panel. The only way to constrain the age of a given painting is by dating the calcite found on top, or under it."

Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London is one of the world's leading authorities on human evolution. He suspects that primitive members of both the modern human and Neanderthal lineages could have co-existed in western Asia.

"Could western Asia have been the conduit for exchanges of ideas between more ancient human populations in Africa and Eurasia, in either direction, and could this have included traditions of artistic expression?" he asked.

"From the new evidence, it could even be argued that the Neanderthals taught traditions of cave art to modern humans when they encountered them about 45,000 years ago, and indeed, modern humans could certainly have encountered earlier Neanderthal markings in caves and embellished them," Stringer told Seeker.

He quickly added, however, that the Sulawesi cave art could have been produced by modern humans, who might have brought such skills from their African ancestral homeland.

Read more at Seeker

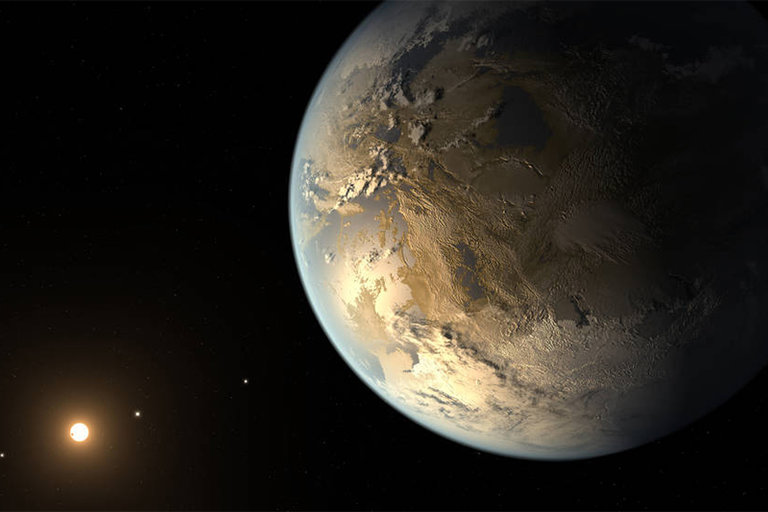

Here’s Another Method for Identifying Life on Other Planets

|

| The search for extraterrestrial life has focused mostly on exoplanets like Kepler-186f, shown here, which circle M-class stars in a “habitable zone” where water may exist. |

Researchers have been able to detect the composition of atmospheres on several of these planets orbiting other stars. But what do they look for exactly, and what factors would indicate potential life?

A group of astronomers from Boston University took a cue from what is unique about our own life-filled planet and propose that looking for oxygen atoms in an exoplanet’s ionosphere would be the best indicator of life.

“[Earth has] atomic oxygen ions, O+, in the ionosphere as a direct consequence of having life on the planet,” Boston University professor of astronomy Michael Mendillo said in a statement. He is the lead author of a new study on the topic published in the journal Nature. “So why don’t we see if we can come up with a criterion where the ionosphere could be a biomarker, not just of possible life but of actual life."

Mendillo and his colleagues didn’t start out looking for life on worlds orbiting distant stars. They were doing a comparative study of all the planetary ionospheres in our own solar system, and were working with NASA’s MAVEN mission at Mars, trying to understand how the molecules that made up the Red Planet’s ionosphere had escaped.

Ever since astronomers have been studying planetary atmospheres, they’ve known that the thin upper atmospheric layer called the ionosphere varies greatly within our solar system. All the planets have them except Mercury, which orbits so close to the sun that its atmosphere is stripped off.

Earth is unique in our solar system because oxygen fills the ionosphere, while other planets have carbon dioxide or hydrogen, primarily. And Earth’s upper atmosphere has a specific type of oxygen — single atoms with a positive charge.

This high concentration of atomic oxygen is due to life on Earth, specifically generated by the process of photosynthesis in which plants, trees, and shrubs use sunlight to synthesize foods from carbon dioxide and water.

“The ionized form of atomic oxygen (O+) is the dominant ion species at the altitude of maximum electron density in only one of the many ionospheres in our Solar System — Earth’s,” the team wrote in their paper. “This ionospheric composition would not be present if oxygenic photosynthesis was not an ongoing mechanism that continuously impacts the terrestrial atmosphere.”

The team proposes that the dominance of O+ ions in the ionosphere can be used to identify a planet in orbit around a star where global-scale biological activity is present. While previous studies have looked for evidence of water in exoplanet atmospheres, the team says finding a peak concentration of oxygen ions (O+) in the ionosphere would be a better indicator.

Other planets in our solar system do have some oxygen in their lower atmospheres, but Earth has much more, about 21 percent. This is because photosynthesis has been going on for the past 3.8 billion years.

“Destroy all the plants on Earth and our atmosphere’s oxygen will vanish away in mere thousands of years,” said Paul Withers, also from BU.

Withers noted that the abundance of O2 near the Earth’s surface leads to an abundance of O+ high in the sky. The oxygen exhaled by plants doesn’t just stay near Earth’s surface, but floats upward. When the O2 gets about 150 kilometers above Earth’s surface, ultraviolet light splits it in two, and the single oxygen atoms then float higher, into the ionosphere, where more ultraviolet light and X-rays from the sun rip electrons from their outer shells, leaving charged oxygen zipping through the air.

This finding, the team says, suggests that scientists seeking extraterrestrial life could perhaps narrow their search area.

Astronomers studying exoplanets have come up with several unique and creative ways of looking for life on other worlds. One group of researchers suggested a technique that Earth-orbiting satellites already use in order to determine land cover that looks for variations in how light is reflected off vegetation, or how trees would cast shadows on the planet. But current telescopes looking at exoplanets do not have this capability.

Others have proposed searching for “glints” of light off oceans or lakes. But as we’ve seen from Saturn’s moon Titan, glints off planetary bodies do not necessarily come from water-filled lakes.

With current technology, astronomers can look for potential life on exoplanets through signs of water molecules in the atmospheres. The chemical composition of exoplanetary atmospheres can provide detail about the physical — and potentially life bearing —conditions on these worlds. The most successful method for doing such a study is the transit spectroscopy method. When an exoplanet passes in front of its host star from our point of view, a small fraction of the stellar light passes through the exoplanetary atmosphere. By measuring the fraction of stellar light able to penetrate the atmosphere at different wavelengths, the chemical composition of the atmosphere can be inferred.

The fraction of stellar light that passes through a transiting exoplanet's atmosphere, however, is very small, which constrains both the telescopes and instruments that can be used and the planetary system that can be observed.

Read more at Seeker

Feb 22, 2018

Magnetic field traces gas and dust swirling around supermassive black hole

Black holes are objects with gravitational fields so strong that not even light can escape their grasp. The centre of almost every galaxy appears to host a black hole, and the one we live in, the Milky Way, is no exception. Stars move around the black hole at speeds of up to 30 million kilometres an hour, indicating that it has a mass of more than a million times our Sun.

Visible light from sources in the centre of the Milky Way is blocked by clouds of gas and dust. Infrared light, as well as X-rays and radio waves, passes through this obscuring material, so astronomers use this to see the region more clearly. CanariCam combines infrared imaging with a polarising device, which preferentially filters light with the particular characteristics associated with magnetic fields.

The new map covers a region about one light year on each side of the supermassive black hole. The map shows the intensity of infrared light, and traces magnetic field lines within filaments of warm dust grains and hot gas, which appear as thin lines reminiscent of brush strokes in a painting.

The filaments, several light years long, appear to meet close to the black hole (at a point below centre in the map), and may indicate where orbits of streams of gas and dust converge. One prominent feature links some of the brightest stars in the centre of the Galaxy. Despite the strong winds flowing from these stars, the filaments remain in place, bound by the magnetic field within them. Elsewhere the magnetic field is less clearly aligned with the filaments. Depending on how the material flows, some of it may eventually be captured and engulfed by the black hole.

The new observations give astronomers more detailed information on the relationship between the bright stars and the dusty filaments. The origin of the magnetic field in this region is not understood, but it is likely that a smaller magnetic field is stretched out as the filaments are elongated by the gravitational influence of the black hole and stars in the galactic centre.

Roche praises the new technique and the result: "Big telescopes like GTC, and instruments like CanariCam, deliver real results. We're now able to watch material race around a black hole 25,000 light years away, and for the first time see magnetic fields there in detail."

The team are using CanariCam to probe magnetic fields in dusty regions in our galaxy. They hope to obtain further observations of the Galactic Centre to investigate the larger scale magnetic field and how it links to the clouds of gas and dust orbiting the black hole further out at distances of several light years.

From Science Daily

No relation between a supermassive black hole and its host galaxy?

|

| Emission from Carbon Monoxide (Left) and Cold Dust (Right) in WISE1029 Observed by ALMA. |

According to a popular scenario explaining the formation and evolution of galaxies and supermassive black holes, radiation from galactic centers -- where supermassive black holes locate -- can significantly influence the molecular gas (such as CO) and the star formation activities of the galaxies. With an ALMA result showing that the ionized gas outflow driven by the supermassive black hole does not necessarily affect its host galaxy, "it has made the co-evolution of galaxies and supermassive black holes more puzzling," Yoshiki explains, "the next step is looking into more data of this kind of galaxies. That is crucial for understanding the full picture of the formation and evolution of galaxies and supermassive black holes."

Answering the question "How did galaxies form and evolve during the 13.8-billion-year history of the universe?" has been one top issue in modern astronomy. Studies already revealed that almost all massive galaxies harbor a supermassive black hole at their centers. In recent findings, studies further revealed that the masses of black holes are tightly correlated with those of their host galaxies. This correlation suggests that supermassive black holes and their host galaxies have evolved together and closely interacted each other as they grow, also known as the co-evolution of galaxies and supermassive black holes.

The gas outflow driven by a supermassive black hole at the galactic center recently has become the focus of attention as it possibly is playing a key role in the co-evolution of galaxies and black holes. A widely accepted idea has described this phenomenon as: the strong radiation from the galactic center in which the supermassive black hole locates ionizes the surrounding gas and affects even molecular gas that is the ingredient of star formation; the strong radiation activates or suppresses the star formation of galaxies. However, "we astronomers do not understand the real relation between the activity of supermassive black holes and star formation in galaxies," says Tohru Nagao, Professor at Ehime University. "Therefore, many astronomers including us are eager to observe the real scene of the interaction between the nuclear outflow and the star-forming activities, for revealing the mystery of the co-evolution."

The team has focused on a particular type of objects called Dust-Obscured Galaxy (DOG) that has a prominent feature: despite being very faint in the visible light, it is very bright in the infrared.

Astronomers are believing that DOGs harbor actively growing supermassive black holes in their nuclei. In particular, one DOG (WISE1029+0501, hereafter WISE1029) is outflowing gas ionized by the strong radiation from its supermassive black hole. WISE1029 is known as an extreme case in terms of ionized gas outflow, and this particular factor has motivated the researchers to see what happens to its molecular gas.

By making use of ALMA's outstanding sensitivity which is excellent in investigating properties of molecular gas and star forming activities in galaxies, the team conducted their research by observing the CO and the cold dust of galaxy WISE1029. After detailed analysis, surprisingly they found, there is no sign of significant molecular gas outflow. Furthermore, star forming activity is neither activated nor suppressed. This indicates that a strong ionized gas outflow launched from the supermassive black hole in WISE1029 neither significantly affect the surrounding molecular gas nor the star formation.

There have been many reports saying that the ionized gas outflow driven by the accretion power of a supermassive black hole has a great impact on surrounding molecular gas. However, it is a very rare case that there is no tight interaction between ionized and molecular gas as the researchers are reporting this time. Yoshiki and the team's result suggests that the radiation from a supermassive black hole does not always affect the molecular gas and star formation of its host galaxy.

Read more at Science Daily

Amateur astronomer captures rare first light from massive exploding star

|

| Supernova 2016gkg (indicated by red bars) in the galaxy NGC 613, located about 40 million light years from Earth in the constellation Sculptor. |

During tests of a new camera, Víctor Buso captured images of a distant galaxy before and after the supernova's "shock breakout" -- when a supersonic pressure wave from the exploding core of the star hits and heats gas at the star's surface to a very high temperature, causing it to emit light and rapidly brighten.

To date, no one has been able to capture the "first optical light" from a supernova, since stars explode seemingly at random in the sky, and the light from shock breakout is fleeting. The new data provide important clues to the physical structure of the star just before its catastrophic demise and to the nature of the explosion itself.

"Professional astronomers have long been searching for such an event," said UC Berkeley astronomer Alex Filippenko, who followed up the discovery with observations at the Lick and Keck observatories that proved critical to a detailed analysis of explosion, called SN 2016gkg. "Observations of stars in the first moments they begin exploding provide information that cannot be directly obtained in any other way."

"Buso's data are exceptional," he added. "This is an outstanding example of a partnership between amateur and professional astronomers."

The discovery and results of follow-up observations from around the world will be published in the Feb. 22 issue of the journal Nature.

On Sept. 20, 2016, Buso of Rosario, Argentina, was testing a new camera on his 16-inch telescope by taking a series of short-exposure photographs of the spiral galaxy NGC 613, which is about 80 million light years from Earth and located within the southern constellation Sculptor.

Luckily, he examined these images immediately and noticed a faint point of light quickly brightening near the end of a spiral arm that was not visible in his first set of images.

Astronomer Melina Bersten and her colleagues at the Instituto de Astrofísica de La Plata in Argentina soon learned of the serendipitous discovery and realized that Buso had caught a rare event, part of the first hour after light emerges from a massive exploding star. She estimated Buso's chances of such a discovery, his first supernova, at one in 10 million or perhaps even as low as one in 100 million.

"It's like winning the cosmic lottery," said Filippenko.

Bersten immediately contacted an international group of astronomers to help conduct additional frequent observations of SN 2016gkg over the next two months, revealing more about the type of star that exploded and the nature of the explosion.

Filippenko and his colleagues obtained a series of seven spectra, where the light is broken up into its component colors, as in a rainbow, with the Shane 3-meter telescope at the University of California's Lick Observatory near San Jose, California, and with the twin 10-meter telescopes of the W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea, Hawaii. This allowed the international team to determine that the explosion was a Type IIb supernova: the explosion of a massive star that had previously lost most of its hydrogen envelope, a species of exploding star first observationally identified by Filippenko in 1987.

Combining the data with theoretical models, the team estimated that the initial mass of the star was about 20 times the mass of our sun, though it lost most of its mass, probably to a companion star, and slimmed down to about 5 solar masses prior to exploding.

Filippenko's team continued to monitor the supernova's changing brightness over two months with other Lick telescopes: the 0.76-meter Katzman Automatic Imaging Telescope and the 1-meter Nickel telescope.

Read more at Science Daily

Some black holes erase your past

But a UC Berkeley mathematician has found some types of black holes in which this law breaks down. If someone were to venture into one of these relatively benign black holes, they could survive, but their past would be obliterated and they could have an infinite number of possible futures.

Such claims have been made in the past, and physicists have invoked "strong cosmic censorship" to explain it away. That is, something catastrophic -- typically a horrible death -- would prevent observers from actually entering a region of spacetime where their future was not uniquely determined. This principle, first proposed 40 years ago by physicist Roger Penrose, keeps sacrosanct an idea -- determinism -- key to any physical theory. That is, given the past and present, the physical laws of the universe do not allow more than one possible future.

But, says UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow Peter Hintz, mathematical calculations show that for some specific types of black holes in a universe like ours, which is expanding at an accelerating rate, it is possible to survive the passage from a deterministic world into a non-deterministic black hole.

What life would be like in a space where the future was unpredictable is unclear. But the finding does not mean that Einstein's equations of general relativity, which so far perfectly describe the evolution of the cosmos, are wrong, said Hintz, a Clay Research Fellow.

"No physicist is going to travel into a black hole and measure it. This is a math question. But from that point of view, this makes Einstein's equations mathematically more interesting," he said. "This is a question one can really only study mathematically, but it has physical, almost philosophical implications, which makes it very cool."

"This ... conclusion corresponds to a severe failure of determinism in general relativity that cannot be taken lightly in view of the importance in modern cosmology," of accelerating expansion, said his colleagues at the University of Lisbon in Portugal, Vitor Cardoso, João Costa and Kyriakos Destounis, and at Utrecht University, Aron Jansen.

As quoted by Physics World, Gary Horowitz of UC Santa Barbara, who was not involved in the research, said that the study provides "the best evidence I know for a violation of strong cosmic censorship in a theory of gravity and electromagnetism."

Hintz and his colleagues published a paper describing these unusual black holes last month in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Beyond the event horizon

Black holes are bizarre objects that get their name from the fact that nothing can escape their gravity, not even light. If you venture too close and cross the so-called event horizon, you'll never escape.

For small black holes, you'd never survive such a close approach anyway. The tidal forces close to the event horizon are enough to spaghettify anything: that is, stretch it until it's a string of atoms.

But for large black holes, like the supermassive objects at the cores of galaxies like the Milky Way, which weigh tens of millions if not billions of times the mass of a star, crossing the event horizon would be, well, uneventful.

Because it should be possible to survive the transition from our world to the black hole world, physicists and mathematicians have long wondered what that world would look like, and have turned to Einstein's equations of general relativity to predict the world inside a black hole. These equations work well until an observer reaches the center or singularity, where in theoretical calculations the curvature of spacetime becomes infinite.

Even before reaching the center, however, a black hole explorer -- who would never be able to communicate what she found to the outside world -- could encounter some weird and deadly milestones. Hintz studies a specific type of black hole -- a standard, non-rotating black hole with an electrical charge -- and such an object has a so-called Cauchy horizon within the event horizon.

The Cauchy horizon is the spot where determinism breaks down, where the past no longer determines the future. Physicists, including Penrose, have argued that no observer could ever pass through the Cauchy horizon point because they would be annihilated.

As the argument goes, as an observer approaches the horizon, time slows down, since clocks tick slower in a strong gravitational field. As light, gravitational waves and anything else encountering the black hole fall inevitably toward the Cauchy horizon, an observer also falling inward would eventually see all this energy barreling in at the same time. In effect, all the energy the black hole sees over the lifetime of the universe hits the Cauchy horizon at the same time, blasting into oblivion any observer who gets that far.

You can't see forever in an expanding universe

Hintz realized, however, that this may not apply in an expanding universe that is accelerating, such as our own. Because spacetime is being increasingly pulled apart, much of the distant universe will not affect the black hole at all, since that energy can't travel faster than the speed of light.

In fact, the energy available to fall into the black hole is only that contained within the observable horizon: the volume of the universe that the black hole can expect to see over the course of its existence. For us, for example, the observable horizon is bigger than the 13.8 billion light years we can see into the past, because it includes everything that we will see forever into the future. The accelerating expansion of the universe will prevent us from seeing beyond a horizon of about 46.5 billion light years.

In that scenario, the expansion of the universe counteracts the amplification caused by time dilation inside the black hole, and for certain situations, cancels it entirely. In those cases -- specifically, smooth, non-rotating black holes with a large electrical charge, so-called Reissner-Nordström-de Sitter black holes -- an observer could survive passing through the Cauchy horizon and into a non-deterministic world.

"There are some exact solutions of Einstein's equations that are perfectly smooth, with no kinks, no tidal forces going to infinity, where everything is perfectly well behaved up to this Cauchy horizon and beyond," he said, noting that the passage through the horizon would be painful but brief. "After that, all bets are off; in some cases, such as a Reissner-Nordström-de Sitter black hole, one can avoid the central singularity altogether and live forever in a universe unknown."

Admittedly, he said, charged black holes are unlikely to exist, since they'd attract oppositely charged matter until they became neutral. However, the mathematical solutions for charged black holes are used as proxies for what would happen inside rotating black holes, which are probably the norm. Hintz argues that smooth, rotating black holes, called Kerr-Newman-de Sitter black holes, would behave the same way.

"That is upsetting, the idea that you could set out with an electrically charged star that undergoes collapse to a black hole, and then Alice travels inside this black hole and if the black hole parameters are sufficiently extremal, it could be that she can just cross the Cauchy horizon, survives that and reaches a region of the universe where knowing the complete initial state of the star, she will not be able to say what is going to happen," Hintz said. "It is no longer uniquely determined by full knowledge of the initial conditions. That is why it's very troublesome."

He discovered these types of black holes by teaming up with Cardoso and his colleagues, who calculated how a black hole rings when struck by gravitational waves, and which of its tones and overtones lasted the longest. In some cases, even the longest surviving frequency decayed fast enough to prevent the amplification from turning the Cauchy horizon into a dead zone.

Hintz's paper has already sparked other papers, one of which purports to show that most well-behaved black holes will not violate determinism. But Hintz insists that one instance of violation is one too many.

Read more at Science Daily

Locomotion of bipedal dinosaurs might be predicted from that of ground-running birds

|

| Ground-running bird model may predict bipedal dinosaur locomotion. |

Previous research has investigated the biomechanics of ground-dwelling birds to better understand the how bipedal non-avian dinosaurs moved, but it has not previously been possible to empirically predict the locomotive forces that extinct dinosaurs experienced, especially those species that were much larger than living birds. Bishop and colleagues examined locomotion in 12 species of ground-dwelling birds, ranging in body mass from 45g to 80kg, as the birds moved at various speeds along enclosed racetracks while cameras recorded their movements and forceplates measured the forces their feet exerted upon the ground.

The researchers found that many physical aspects of bird locomotion change continuously as speed increases. This supports previous evidence that unlike humans, who have distinct "walking" and "running" gaits, birds move in a continuum from "walking" to "running." The authors additionally observed consistent differences in gait and posture between small and large birds.

The researchers used their data to construct the biomechanically informative, regression-derived statistical (BIRDS) Model, which requires just two inputs -- body mass and speed -- to predict basic features of bird locomotion, including stride length and force exerted per step. The model performed well when tested against known data. While more data are needed to improve the model, and it is unclear if it can be extrapolated to animals of much larger body mass, the researchers hope that it might help predict features of non-avian dinosaur locomotion using data from fossils and footprints.

From Science Daily

Feb 21, 2018

Brain size of human ancestors evolved gradually over 3 million years

|

| These are models of human ancestors brain size compared to modern day humans. |

The research, published this week in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, shows that the trend was caused primarily by evolution of larger brains within populations of individual species, but the introduction of new, larger-brained species and extinction of smaller-brained ones also played a part.

"Brain size is one of the most obvious traits that makes us human. It's related to cultural complexity, language, tool making and all these other things that make us unique," said Andrew Du, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Chicago and first author of the study. "The earliest hominins had brain sizes like chimpanzees, and they have increased dramatically since then. So, it's important to understand how we got here."

Du began the work as a graduate student at the George Washington University (GW). His advisor, Bernard Wood, GW's University Professor of Human Origins and senior author of the study, gave his students an open-ended assignment to understand how brain size evolved through time. Du and his fellow students, who are also co-authors on the paper, continued working on this question during his time at George Washington, forming the basis of the new study.

"Think about the entrance to a building. You can reach the front door by walking up a ramp, or you can take the steps," Wood said. "The conventional wisdom was that our large brains had evolved because of a series of step-like increases each one making our ancestors smarter. Not surprisingly the reality is more complex, with no clear link between brain size and behavior."

"The moral is this: When you don't understand something ask a bunch of bright and motivated students to figure it out," he said.

Du and his colleagues compared published research data on the skull volumes of 94 fossil specimens from 13 different species, beginning with the earliest unambiguous human ancestors, Australopithecus, from 3.2 million years ago to pre-modern species, including Homo erectus, from 500,000 years ago when brain size began to overlap with that of modern-day humans.

The researchers saw that when the species were counted at the clade level, or groups descending from a common ancestor, the average brain size increased gradually over three million years. Looking more closely, the increase was driven by three different factors, primarily evolution of larger brain sizes within individual species populations, but also by the addition of new, larger-brained species and extinction of smaller-brained ones. The team also found that the rate of brain size evolution within hominin lineages was much slower than how it operates today, although why this discrepancy exists is still an open question.

The study quantifies for the first time when and by how much each of these factors contributes to the clade-level pattern. Du said he likens it to how a football coach might build a roster of bigger, strong players. One way would be to make all the players hit the weight room to bulk up. But the coach could also recruit new, larger players and cut the smallest ones.

Read more at Science Daily

Did humans speak through cave art? Ancient drawings and language's origins

|

| Ancient art in the Altai Mountains, Russia. While the world’s best-known cave art exists in France and Spain, examples of it abound throughout the world. |

More precisely, some specific features of cave art may provide clues about how our symbolic, multifaceted language capabilities evolved, according to a new paper co-authored by MIT linguist Shigeru Miyagawa.

A key to this idea is that cave art is often located in acoustic "hot spots," where sound echoes strongly, as some scholars have observed. Those drawings are located in deeper, harder-to-access parts of caves, indicating that acoustics was a principal reason for the placement of drawings within caves. The drawings, in turn, may represent the sounds that early humans generated in those spots.

In the new paper, this convergence of sound and drawing is what the authors call a "cross-modality information transfer," a convergence of auditory information and visual art that, the authors write, "allowed early humans to enhance their ability to convey symbolic thinking." The combination of sounds and images is one of the things that characterizes human language today, along with its symbolic aspect and its ability to generate infinite new sentences.

"Cave art was part of the package deal in terms of how homo sapiens came to have this very high-level cognitive processing," says Miyagawa, a professor of linguistics and the Kochi-Manjiro Professor of Japanese Language and Culture at MIT. "You have this very concrete cognitive process that converts an acoustic signal into some mental representation and externalizes it as a visual."

Cave artists were thus not just early-day Monets, drawing impressions of the outdoors at their leisure. Rather, they may have been engaged in a process of communication.

"I think it's very clear that these artists were talking to one another," Miyagawa says. "It's a communal effort."

The paper, "Cross-modality information transfer: A hypothesis about the relationship among prehistoric cave paintings, symbolic thinking, and the emergence of language," is being published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology. The authors are Miyagawa; Cora Lesure, a PhD student in MIT's Department of Linguistics; and Vitor A. Nobrega, a PhD student in linguistics at the University of Sao Paulo, in Brazil.

Re-enactments and rituals?

The advent of language in human history is unclear. Our species is estimated to be about 200,000 years old. Human language is often considered to be at least 100,000 years old.

"It's very difficult to try to understand how human language itself appeared in evolution," Miyagawa says, noting that "we don't know 99.9999 percent of what was going on back then." However, he adds, "There's this idea that language doesn't fossilize, and it's true, but maybe in these artifacts [cave drawings], we can see some of the beginnings of homo sapiens as symbolic beings."

While the world's best-known cave art exists in France and Spain, examples of it exist throughout the world. One form of cave art suggestive of symbolic thinking -- geometric engravings on pieces of ochre, from the Blombos Cave in southern Africa -- has been estimated to be at least 70,000 years old. Such symbolic art indicates a cognitive capacity that humans took with them to the rest of the world.

"Cave art is everywhere," Miyagawa says. "Every major continent inhabited by homo sapiens has cave art. ... You find it in Europe, in the Middle East, in Asia, everywhere, just like human language." In recent years, for instance, scholars have catalogued Indonesian cave art they believe to be roughly 40,000 years old, older than the best-known examples of European cave art.

But what exactly was going on in caves where people made noise and rendered things on walls? Some scholars have suggested that acoustic "hot spots" in caves were used to make noises that replicate hoofbeats, for instance; some 90 percent of cave drawings involve hoofed animals. These drawings could represent stories or the accumulation of knowledge, or they could have been part of rituals.

In any of these scenarios, Miyagawa suggests, cave art displays properties of language in that "you have action, objects, and modification." This parallels some of the universal features of human language -- verbs, nouns, and adjectives -- and Miyagawa suggests that "acoustically based cave art must have had a hand in forming our cognitive symbolic mind."

Future research: More decoding needed

To be sure, the ideas proposed by Miyagawa, Lesure, and Nobrega merely outline a working hypothesis, which is intended to spur additional thinking about language's origins and point toward new research questions.

Regarding the cave art itself, that could mean further scrutiny of the syntax of the visual representations, as it were. "We've got to look at the content" more thoroughly, says Miyagawa. In his view, as a linguist who has looked at images of the famous Lascaux cave art from France, "you see a lot of language in it." But it remains an open question how much a re-interpretation of cave art images would yield in linguistics terms.

The long-term timeline of cave art is also subject to re-evaluation on the basis of any future discoveries. If cave art is implicated in the development of human language, finding and properly dating the oldest known such drawings would help us place the orgins of language in human history -- which may have happened fairly early on in our development.

"What we need is for someone to go and find in Africa cave art that is 120,000 years old," Miyagawa quips.

At a minimum, a further consideration of cave art as part of our cognitive development may reduce our tendency to regard art in terms of our own experience, in which it probably plays a more strictly decorative role for more people.

Read more at Science Daily

Ancient DNA tells tales of humans' migrant history

No longer. Now there's a powerful new approach for illuminating the world before the dawn of written history -- reading the actual genetic code of our ancient ancestors. Two papers published in the journal Nature on February 21, 2018, more than double the number of ancient humans whose DNA has been analyzed and published to 1,336 individuals -- up from just 10 in 2014.

The new flood of genetic information represents a "coming of age" for the nascent field of ancient DNA, says lead author David Reich, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator at Harvard Medical School -- and it upends cherished archeological orthodoxy. "When we look at the data, we see surprises again and again and again," says Reich.

Together with his lab's previous work and that of other pioneers of ancient DNA, the Big Picture message is that our prehistoric ancestors were not nearly as homebound as once thought. "There was a view that migration is a very rare process in human evolution," Reich explains. Not so, says the ancient DNA. Actually, Reich says, "the orthodoxy -- the assumption that present-day people are directly descended from the people who always lived in that same area -- is wrong almost everywhere."

Instead, "the view that's emerging -- for which David is an eloquent advocate -- is that human populations are moving and mixing all the time," says John Novembre, a computational biologist at the University of Chicago.

Stonehenge's Builders Largely Vanish

In one of the new papers, Reich and a cast of dozens of collaborators chart the spread of an ancient culture known by its stylized bell-shaped pots, the so-called Bell Beaker phenomenon. This culture first spread between Iberia and central Europe beginning about 4,700 years ago. By analyzing DNA from several hundred samples of human bones, Reich's team shows that only the ideas -- not the people who originated them -- made the move initially. That's because the genes of the Iberian population remain distinct from those of the central Europeans who adopted the characteristic pots and other artifacts.

But the story changes when the Bell Beaker culture expanded to Britain after 4,500 years ago. Then, it was brought by migrants who almost completely supplanted the island's existing inhabitants -- the mysterious people who had built Stonehenge -- within a few hundred years. "There was a sudden change in the population of Britain," says Reich. "It was an almost complete replacement."

For archeologists, these and other findings from the study of ancient DNA are "absolutely sort of mind-blowing," says archaeologist Barry Cunliffe, a professor emeritus at the University of Oxford. "They are going to upset people, but that is part of the excitement of it."

Vast Migration from the Steppe

Consider the unexpected movement of people who originally lived on the steppes of Central Asia, north of the Black and Caspian seas. About 5,300 years ago, the local hunter-gatherer cultures were replaced in many places by nomadic herders, dubbed the Yamnaya, who were able to expand rapidly by exploiting horses and the new invention of the cart, and who left behind big, rich burial sites.

Archeologists have long known that some of the technologies used by the Yamnaya later spread to Europe. But the startling revelation from the ancient DNA was that the people moved, too -- all the way to the Atlantic coast of Europe in the west to Mongolia in the east and India in the south. This vast migration helps explain the spread of Indo-European languages. And it significantly replaced the local hunter-gatherer genes across Europe with the indelible stamp of steppe DNA, as happened in Britain with the migration of the Bell Beaker people to the island.

"This whole phenomenon of the steppe expansion is an amazing example of what ancient DNA can show," says Reich. And, adds Cunliffe, "no one, not even archeologists in their wildest dreams, had expected such a high steppe genetic content in the populations of northern Europe in the third millennium B.C."

This ancient DNA finding also explains the "strange result" of a genetic connection that had been hinted at in the genomes of modern-day Europeans and Native Americans, adds Chicago's Novembre. The link is evidence from people who lived in Siberia 24,000 years ago, whose telltale DNA is found both in Native Americans, and in the Yamnaya steppe populations and their European descendants.

New Insights from Southeastern Europe

Reich's second new Nature paper, on the genomic history of southeastern Europe, reveals an additional migration as farming spread across Europe, based on data from 255 individuals who lived between 14,000 and 2,500 years ago. It also adds a fascinating new nugget -- the first compelling evidence that the genetic mixing of populations in Europe was biased toward one sex.

Hunter-gatherer genes remaining in northern Europeans after the influx of migrating farmers came more from males than females, Reich's team found. "Archaeological evidence shows that when farmers first spread into northern Europe, they stopped at a latitude where their crops didn't grow well," he says. "As a result, there were persistent boundaries between the farmers and the hunter-gatherers for a couple of thousand years." This gave the hunter-gatherers and farmers a long time to interact. According to Reich, one speculative scenario is that during this long, drawn-out interaction, there was a social or power dynamic in which farmer women tended to be integrated into hunter-gatherer communities.

So far that's only a guess, but the fact that ancient DNA provides clues about the different social roles and fates of men and women in ancient society "is another way, I think, that these data are so extraordinary," says Reich.

Advanced Machines

These scientific leaps forward have been fueled by three key developments. One is the dramatic cost reduction (and speed increase) in gene sequencing made possible by advanced machines from Illumina and other companies. The second is a discovery spearheaded by Ron Pinhasi, an archaeologist at University College Dublin. His group showed that the petrous bone, containing the tiny inner ear, harbors 100 times more DNA than other ancient human remains, offering a huge increase in the amount of genetic material available for analysis. The third is a method implemented by Reich for reading the genetic codes of 1.2 million carefully chosen variable parts of DNA (known as single nucleotide polymorphisms) rather than having to sequence entire genomes. That speeds the analysis and reduces its cost even further.

The new field made a splash when Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, working with Reich and many other colleagues, used ancient DNA to prove that Neanderthals and humans interbred. Since then, the number of ancient humans whose DNA Reich has analyzed has risen exponentially. His lab has generated about three-quarters of the world's published data and, included unpublished data, has now reached 3,700 genomes. "Every time we jump an order of magnitude in the number of individuals, we can answer questions that we couldn't even have asked before," says Reich.

Now, with hundreds of thousands of ancient skeletons (and their petrous bones) still to be analyzed, the field of ancient DNA is poised to both pin down current questions and tackle new ones. For example, Reich's team is working with Cunliffe and others to study more than 1,000 samples from Britain to more accurately measure the replacement of the island's existing gene pool by the steppe-related DNA from the Bell Beaker people. "The evidence we have for a 90 percent replacement is very, very suggestive, but we need to test it a bit more to see how much of the pre-Beaker population really survived," explains Cunliffe.

Beyond that, ancient DNA offers the promise of studying not only the movements of our distant ancestors, but also the evolution of traits and susceptibilities to diseases. "This is a new scientific instrument that, like the microscope when it was invented in the seventeenth century, makes it possible to study aspects of biology that simply were not possible to examine before," explains Reich. In one example, scientists at the University of Copenhagen found DNA from plague in the steppe populations. If the groups that migrated to Britain after 4,500 years ago brought the disease with them, that could help explain why the existing population shrank so quickly.

Read more at Science Daily

These Stunning Microscopic Visuals Make It Easy to Envision Chemistry

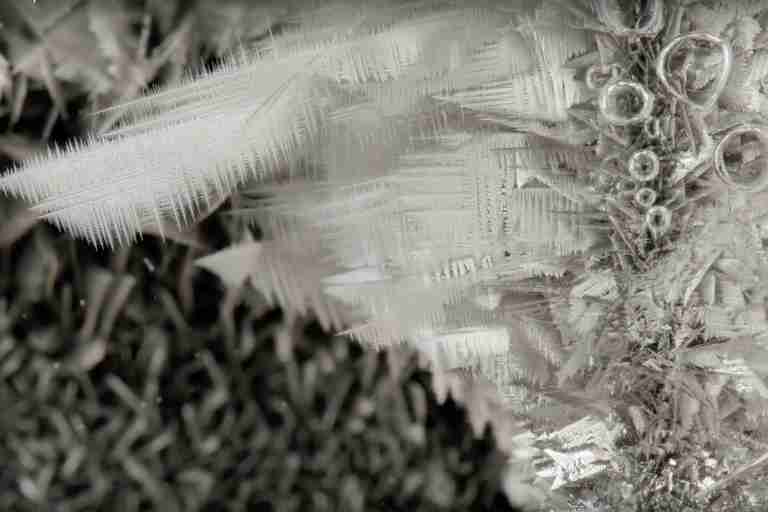

|

| An image of metal displacement, from Envisioning Chemistry. |

That's the guiding principle behind Envisioning Chemistry, an ongoing art-meets-science collaboration between the Chinese Chemical Society and an online education initiative called Beauty of Science. The idea is to make chemistry more engaging to the general public by creating images and videos that bring the fascinating world of microscopic chemical reactions to life.

In a series of short videos (viewable below), filmmaker and photographer Wenting Zhu reveals the improbable beauty of chemical processes like precipitation, combustion, and those oddly captivating chemical byproducts known as bubbles. Zhu captured the images in the Envisioning Chemistry series using high-speed cameras, a Lumix GH4100mm macro lens, an Olympus SXZ16 microscope, and thermal imaging, unveiling a tiny world of wonder.

“Envisioning Chemistry tries to capture a purely objective record of chemical reactions by using a macro lens and a microscope,” Zhu told Seeker. “In this way of viewing, we have a chance to look at tiny shapes and textures generated in this process that allows us to perceive the unseen.”

|

| An image of metal displacement, from Envisioning Chemistry. |

Zhu, who is also an accomplished painter, graduated in 2016 from the Academy of Arts and Design at Tsinghua University. She is now working with Beauty of Science, an educational initiative that distributes videos and images to schools and maintains online libraries of its work on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and Vimeo.

“I think video can be a powerful media for communicating science to the general public,” said Beauty of Science founder Yan Liang, who also films and edits materials and serves on the faculty at the University of Science and Technology of China.

Read more at Seeker

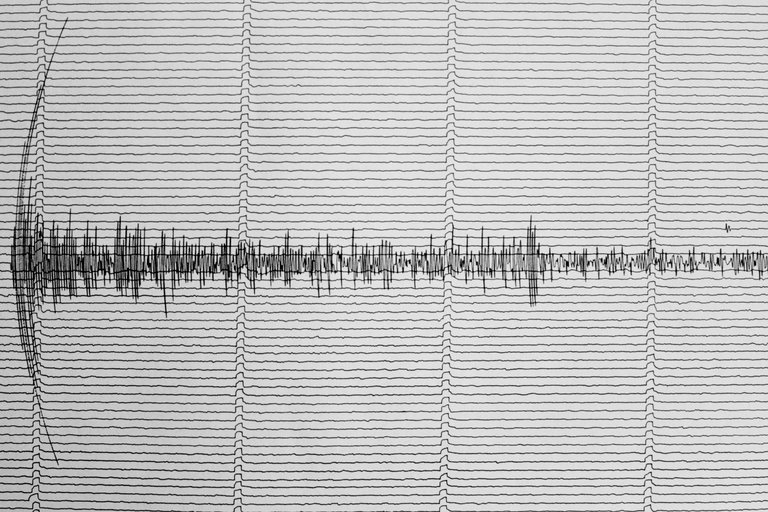

AI Earthquake Tracker Is Inspired by Speech Recognition Technology

The state of Oklahoma has witnessed a stunning rise in the frequency of earthquakes, which has been linked to an increase in the use of fracking technology in the oil and gas sector. Starting in 2009, the annual number of quakes measuring above magnitude 3.0 in the state exploded from fewer than three to as many as 903 in 2015.

Now, all this seismic activity has prompted scientists to develop a new tool for tracking it — drawing on speech recognition technology.

The result is a system dubbed ConvNetQuake that’s designed to detect even the tiniest earthquake against background geological noise in the same way that a smartphone can discern a human voice inside a car that’s rumbling down the highway.

The system represents an upgrade in sensitivity and detection-speed from current methods, according to its designers. When tested against historical field data, the new approach uncovered 17 times more quakes than were recorded in the Oklahoma Geological Survey standard earthquake catalog.

“We’ve trained the algorithm to understand what’s just noise and what’s an earthquake, and also where the earthquake is coming from,” Thibaut Perol, lead author of a new paper describing the system, told Seeker. Perol works on voice-recognition and artificial intelligence at a startup in Washington DC called *gramLabs.

Fracking is a relatively new form of crude oil and natural gas production that’s dramatically revived US hydrocarbon output.

The process involves blasting chemical-laced water below ground to fracture rock formation and withdraw oil or natural gas, opening up previously inaccessible reserves. But excess water is seeping out into dormant faults, and is thought to be causing them to slip, resulting in earthquakes.

Most existing earthquake-detection methods are designed to detect moderate-to-large events. As a consequence, they miss many low-magnitude earthquakes that get masked by background seismic noise.

But picking up the smaller quakes allows researchers to paint a more precise picture of all the earthquake activity in a place like Oklahoma, yielding a better understanding of the location of the quakes, whether they might be shifting, and whether the frequency is rising or falling. The extra data could eventually yield insight into whether a big one is coming, Perol said.

That’s because the art of predicting earthquakes remains essentially one of modeling likely future risk based on the patterns that have come before. In spite of some promising new research in the field of earthquake forecasting, the state-of-the-art is still limited, essentially, to an understanding of how many quakes have come before, and how often.

Existing platforms for detecting earthquakes use three stations to triangulate the source of the rumbling. The new method isn’t just more sensitive, but requires only one detection location.

Read more at Seeker

Now, all this seismic activity has prompted scientists to develop a new tool for tracking it — drawing on speech recognition technology.

The result is a system dubbed ConvNetQuake that’s designed to detect even the tiniest earthquake against background geological noise in the same way that a smartphone can discern a human voice inside a car that’s rumbling down the highway.

The system represents an upgrade in sensitivity and detection-speed from current methods, according to its designers. When tested against historical field data, the new approach uncovered 17 times more quakes than were recorded in the Oklahoma Geological Survey standard earthquake catalog.