|

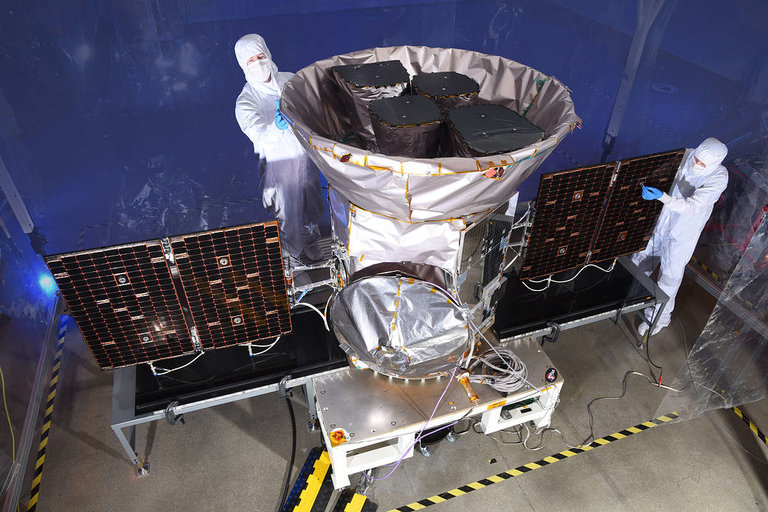

| NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite |

TESS is scheduled to launch from Vandenberg Air Force Base April 16 and will make its way to an Earth orbit with lowest and highest altitudes of 67,000 miles and 232,000 miles. It will study different parts of the sky in observing campaigns of almost one month each, ferrying data back to Earth about what it sees.

Like Kepler, TESS will examine stars and look for the telltale dimming, or “transit,” that takes place when a planet goes across the star's face. The observatory's information will be beamed back to the ground where other telescopes can look for small tugs or wobbles in the star's position, which would confirm a planet has been discovered.

"TESS was designed so the targets would be optimally based for ground-based follow up," principal investigator George Ricker, a senior scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told Seeker. "We want to make sure we can communicate to ground-based observers the information that we get in terms of candidate transit events, or planets."

With 200,000 high-priority targets, TESS investigators expect the first possible planets will come back to Earth within just a few weeks or months. The mission is currently funded for two years. In that time, it will locate hundreds of possible exoplanets, including a few dozen that are close to the size of Earth. Kepler has already located well over 2,000 planets, but the TESS stars will be brighter, closer, and easier to examine.

Kepler investigators, however, will get the second chance to look at planets discovered by the telescope during the second year of TESS’s operations. At first, TESS will spend a year moving its view around the southern hemisphere. Kepler's original field of view was the constellation Cygnus, in the north. Sometime during its second year of operations, TESS will spend a month staring at the same spot that Kepler examined for four years, between 2009 and 2013.

Engineers constructed TESS to last well beyond its original mission lifetime, as long as funding persists. The telescope will act as a finder telescope, searching for objects that are interesting, which other telescopes might zoom in on. A prominent follow-up telescope will be the James Webb Space Telescope, which is now expected to launch in 2020. Ideally, TESS and James Webb observations will overlap.

"The longer the mission will operate, the more precisely we can determine the properties of the [planetary] transits," Ricker said. Once they pinpoint the time it takes for a planet to go around a star, Webb can peer at the planet to learn more about its atmosphere. Other instruments, such as HARPS (High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher) at the La Silla Observatory, could measure a planet’s wobbles in order to estimate its mass.

Read more at Seeker

No comments:

Post a Comment