|

| The Three Witches, by Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) |

Even leading scientists are surprised by the current prevalence of witchcraft beliefs, which should not be confused with the contemporary nature-based Wicca pagan religion that focuses on benevolence.

For example, when evolutionary anthropologist Ruth Mace of University College London and her team recently traveled to southwestern China to study the rural population there, witchcraft was hardly on their minds.

"Our original interest was to study cooperative networks between households," Mace told Seeker. "We were not expecting this factor to be especially widespread or important."

The researchers observed that among the Mosuo ethnic group, female heads of households and their daughters are called zhu when others believe that they have magical powers and engage in food poisoning.

"We were surprised it was 13 percent of households in our study site that were labeled with this tag," added Mace. "And we were surprised that it generated such clear assortment within the population on social networks."

Prior research on witchcraft, such as that conducted by the late British anthropologist E.E. Evans-Pritchard (1902–1973), argued that fear of victimization through witchcraft accusations promotes cooperation in small-scale societies. Evans-Pritchard came to this conclusion after studying the Zande people of north-central Africa. Still other scientists have suggested that witchcraft labels are used to mark untrustworthy or uncooperative individuals.

To further investigate these possibilities, Mace and her team conducted interviews and gift-giving experiments in 800 Mosuo households across five villages in Sichuan Province. The findings are published in the journal Nature Human Behavior.

For the gift-giving experiments, Mace, senior author Yi Tao of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and their colleagues provided a subsample of the Mosuo households with money. Participants were then allowed to give the money as gifts to up to three adult individuals in any other household in the study site. The scientists also collected data from Mosuo working groups on farms, during planting and harvesting times, to identify who was helping whom in their fields.

The researchers found that zhu households were no less cooperative than others, suggesting that the witchcraft label is not used to mark uncooperative or untrustworthy families.

Mace and her team additionally determined that the accusations divided the overall Mosuo social network in two: those with the zhu label and those without. Zhu households were largely excluded from intermarriage and from trading farm labor with non-zhu households. Zhu households made up for this, at least in part, by preferentially interacting with each other in small sub-networks.

Mace said very few people wanted to talk directly with her and her colleagues about the situation, given that it remains a very sensitive topic. Some of those accused of witchcraft, Mace shared, "told us not to worry about eating in their house," indicating their constant awareness of being labeled "poison givers," but that they did not believe the accusations themselves.

As with the zhu labeling, witchcraft beliefs worldwide often involve notions of poisoning. Women frequently are the primary cooks in homes — whether they want to be or not — so it could be that supernatural explanations for stomach distress first emerged during times when biological parasitism and other reasonable scientific explanations for food-related health issues were not yet available.

"Hence," Mace explained, "in non-scientific eras, they may have filled a need for an explanation for a frightening or harmful event or illness."

"However, we do not think actual cases of parasitism are what are prompting most accusations — probably just scapegoating for any harmful event," she continued. "Or, in some cases, the tag is said to have been inherited from your mother, so the original cause may have been long ago."

|

| Mosuo women visit a Buddhist temple in Yongning, Yunnan Province. |

"Anecdotes in the literature about reasons for witchcraft accusations are very diverse," Mace explained. "Some anecdotes focus on beauty or wealth, so there may be an element of spite or leveling."

Among the Mosuo, there is competition for desirable mates and skilled farm help, with the zhu accusations likely affecting both.

Boris Gershman, an assistant professor of economics at American University, told Seeker that he agrees with the new findings, which support those of a study he did in 2016 on nineteen countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, such as Tanzania, South Africa, Cameroon, Namibia, Mozambique, and Zambia.

For that research, published in the Journal of Development Economics, he used survey data to show that the local prevalence of witchcraft beliefs is strongly associated with antisocial attitudes and behavior, including diminished trust, charitable giving and participation in group activities.

"Similarly, the new paper by Mace et al. shows that beliefs in zhu among the Mosuo limit cooperation by restricting prosocial behavior primarily to the members of one's own group," Gershman said. "Thus, both studies point to the possibility of an adverse effect of witchcraft and related beliefs on what is known as 'social capital.'"

The research indicates that witchcraft beliefs can not only halt social cohesion in populations, but also have the potential for curtailing economic progress in those areas.

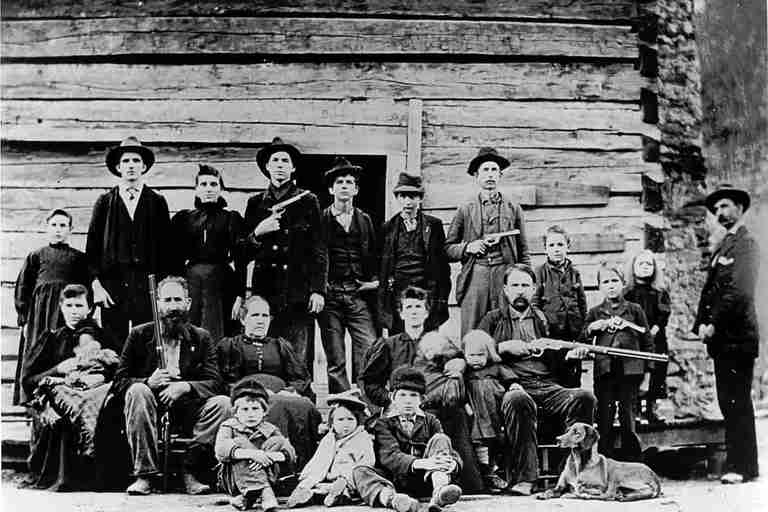

The outcome is somewhat similar to traditional family feuds in the US like the Hatfields and McCoys, where one clan wars with another, yet preferentially associates with its own kind. The episode initiating the discord could have happened long ago, yet just being related to a supposed guilty party could be reason enough to stigmatize a family over generations. As the rift escalates and continues, opportunities presumably diminish for sharing knowledge and resources beyond the smaller, trusted group.

|

| The Hatfield clan, photographed in 1897 |

A more general version of this theory, Gershman said, is that witchcraft beliefs represent a form of social control that forces individuals to conform to local norms under the fear of facing witchcraft accusations in case of deviation from those norms.

"This may have been important in the past for group survival, but it obviously comes at a steep cost of social and economic immobility caused by fears of bewitchment and witchcraft accusations," Gershman said.

He added that one reason witchcraft beliefs still exist is that "children tend to copy their parents, and parents tend to socialize children to their own values and beliefs, both of which contribute to cultural persistence."

The ongoing prevalence of witch labeling in many parts of the world can do far more harm than just tarnishing reputations.

In September of last year, a Lancaster University-led team held a United Nations Witchcraft and Human Rights Expert Workshop to shed light on the thousands of cases of people accused of witchcraft each year globally, often with fatal consequences.

"Accusations of witchcraft are almost exclusively targeted against the weakest and most vulnerable members of society," Gary Foxcroft told Seeker.

Foxcroft was a co-organizer of the workshop and is the founder and executive director of The Witchcraft & Human Rights Information Network (WHRIN).

"Very rarely does WHRIN document any cases against men," Foxcroft continued. "The people often behind the accusations, often male witch-doctors or pastors in Pentecostal churches, label women, children, the elderly, and disabled as witches, as they have the least power and are therefore less likely to be able to hold them to account in any way."

A related problem concerns the way that albino people are often treated in such regions. Throughout much of Africa, people with albinism are believed to hold certain magical powers, Foxcroft explained, adding "this belief is fueling an epidemic of the killing of people with albinism across parts of Africa."

WHRIN documents that over the past decade, 528 attacks on people with albinism have been reported in 28 African countries.

"Poverty, lack of access to basic healthcare facilities, strength of belief in the power of witch-doctors and pastors, environmental crises, misperceptions of public health conditions, weak judiciary, corrupt police forces, and weak governance all play a role," Foxcroft said.

Consistent with the practice, Gershman found that "representatives of ethnic groups which were more heavily exposed to the Atlantic slave trade in the past are more likely to believe in witchcraft today, thus establishing a link between historical trauma and contemporary culture."

African descendants of these cultures in Latin America today, for example, are substantially more likely to believe in witchcraft relative to other racial groups there.

"Such beliefs are not isolated to Africa, though," said Foxcroft, who mentioned that he was "very shocked" by recent data showing that nearly 1,500 cases of child abuse in the UK were linked to concerns over witchcraft and demonic possession.

Justin Humphreys, executive director of safeguarding at the Churches' Child Protection Advisory Service, told The Telegraph "that an increasing number of children in the UK are being harmed in the belief that ‘it will get the devil out of them.' We should be taking this as a call to re-energize the national effort to educate communities and professionals and safeguard all our children.”

Foxcroft and his colleagues are pushing for a UN Human Rights Council resolution that has the goal of allowing people worldwide the ability to live freely without fear of their rights being abused due to the belief in witchcraft. "[The resolution] would be a starting point for the international community to recognize the scale and severity of the abuses that are taking place, which have largely slipped under the radar to date," he said.

Foxcroft and others suggest that additional needed steps include reviewing and amending related laws; carrying out widespread community enlightenment campaigns to demystify the public health conditions associated with witchcraft; regulating witch-doctors and faith leaders; training of judiciary, police, and social workers; and providing support to victims of abuse.

The problem is a complex one to solve, as many people — like the Mosuo — hesitate to talk about long-standing cultural beliefs. Additionally, care must be taken to distinguish harmful "witchcraft" associations from the worldwide neo-pagan Wicca movement that has a rich history of promoting social justice and living peacefully in harmony with nature.

Many Native American and South American traditions also have their origins in peace-promoting "witchcraft," as do numerous other cultures worldwide. Nearly all popular holidays in the Western world, from Christmas to Halloween, include beloved traditions derived from pagan and often witch-centric mythology, such as kissing under the "magical, good luck plant" mistletoe and celebrating bunnies at Easter time.

The word "witchcraft" itself has been abused by those wishing to disguise their real motivations.

The US House Intelligence Committee last year confirmed that Russia's Internet Research Agency authored tens of thousands of social media posts, many of which targeted Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton. Thousands of these fake social media messages attempted to link Clinton and her associates to witchcraft and satanic rituals, and used other tactics to, as former US ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul said, "sow doubt and discord in America."

Read more at Seeker

No comments:

Post a Comment