|

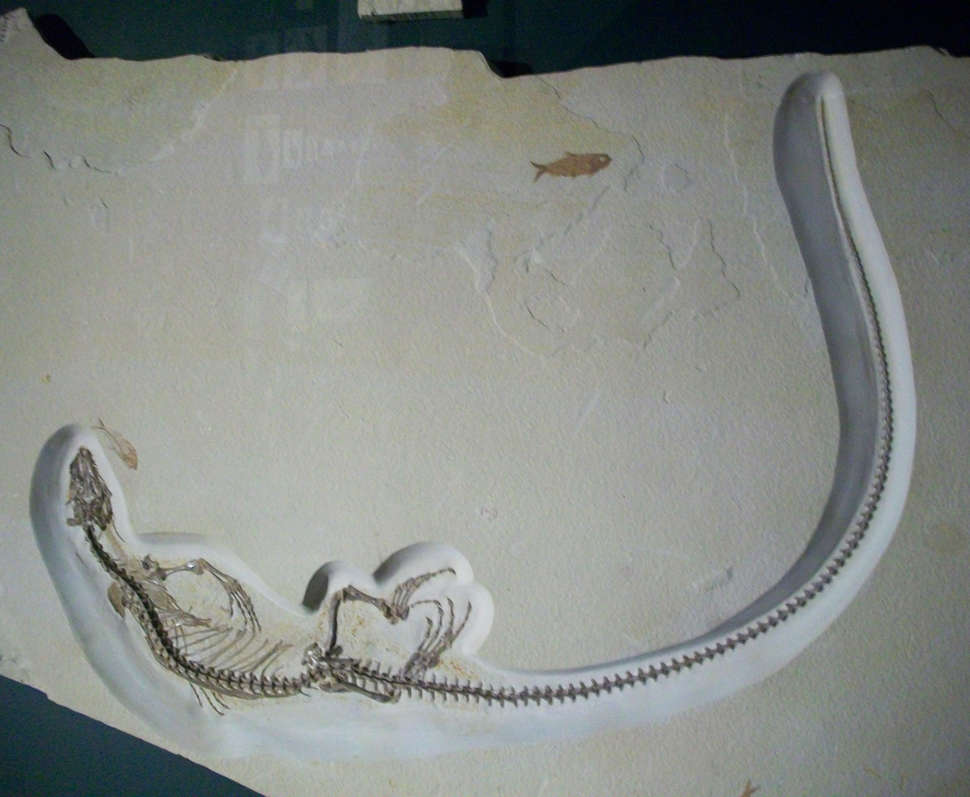

| Fossil of Saniwa ensidens in the Field Museum of Natural History |

The extra two eyes are photosensory structures at the top of the head known as the pineal and parapineal organs. Scientists are still trying to determine all of the functions of these organs, but it is known that they play key roles in orientation and in circadian and annual cycles.

The pineal organ is found in a number of lower vertebrates, such as fishes and frogs, but the parapineal organ is less common. Krister Smith of the Senckenberg Research Institute, however, has long suspected that ancient lizards might have had both of the photosensory structures along with two more typical eyes.

"The idea first germinated when, as a graduate student, I was surveying the diversity of fossil lizards in the Yale collections," Smith said. "In one case, there were contradictory interpretations of the third eye in the parietal bone by different experts. It was clear that there were two large holes in the bone, one behind the other, and I recalled that there were two pineal organs."

Smith admits that it was a "wacky" idea to search for an ancient lizard with four eyes, but she and her team did just that.

They scoured museum specimens collected nearly 150 years ago at Grizzly Buttes, a site in the Bridger Basin of Wyoming. CT scans revealed that two different individuals from an extinct species of monitor lizard (Saniwa ensidens) had spaces where the extra two eyes would have been.

The discovery, reported in the journal Current Biology, documents the first known four-eyed jawed vertebrate.

"As a scientist, one has lots of ideas, but many — even most of them — don't pan out, and the more idiosyncratic an idea is, the more likely it is to fail," Smith said, adding that she was thrilled when her suspicions about fossilized lizards proved to be correct.

The discovery sheds light on the evolution of the extra eyes.

|

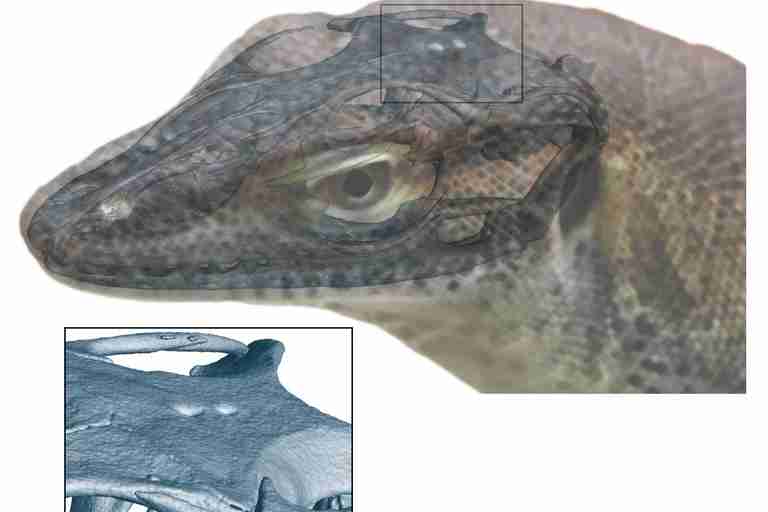

| This image depicts a reconstruction of what the extinct monitor lizard might have looked like. The parietal and pineal foramina are visible on the overlaid skull. |

What is known is that the earliest mammals — our distant ancestors — did not just have two eyes.

"Stem mammals had three eyes," Smith explained. "It has been proposed that the nocturnal phase of evolution in mammalian ancestors led to the disappearance of the third eye in that lineage, and perhaps something similar happened in other tetrapod groups."

Many tetrapods, or four-footed animals, therefore might have lost their third eye when some became active at night and presumably didn't need the additional photosensory organs.

Humans and most other mammals retain no lingering evidence of a third eye.

"In particular in humans, the cerebrum is so massively expanded that it thickly and completely covers the pineal organ, making it virtually impossible for any photons to reach it," Smith said. "Also, the parapineal organ is regarded as completely absent."

In rats, however, the pineal organ is close to the surface. Some photosensitive proteins are still expressed in the organ in embryonic rats, suggesting that the third eye didn't completely disappear in the rodent lineage.

Smith and her team are not sure which organ — the pineal or parapineal — led to the formation of the third eye in early mammals. When that mystery is solved, they should gain a better understanding of why the extra eye was lost over time in mammals.

What is clearer is that the third eye of today's lizards, the pineal organ, evolved independently from the third eye of other jawed vertebrates.

"We should stress that the idea that the lizard third eye is not the same as the third eye of frogs or fish was proposed before," Smith said. "But it has not been universally accepted. By finding a species in which both pineal organs were simultaneously developed as eyes, where the front one was clearly the typical lizard third eye, we could confirm this idea."

Although the extinct monitor's extra eyes were located close together, the researchers do not think that they functioned as a pair in the same way that typical eyes do.

"They are indeed closely spaced, but their central neural connections with the rest of the brain are different," Smith explained.

Saniwa ensidens lived in parts of Wyoming and Europe during the Eocene epoch around 48 million years ago. It holds the distinction of being the first fossil lizard ever known from North America. Now it has yet another claim to animal fame — at least for now.

The new finding "tells us how easy it is, in terms of evolution, to self-assemble a complex organ under certain circumstances,” said Bhullar, a paleontologist at Yale. “Eyes are classically thought of as these remarkably complex structures. In fact, the brain is just waiting to make eyes at all times.”

He added that eyes are "fundamentally a part of the brain" and that their formation "is part of the process of how the brain comes in contact with part of the skin."

Smith said that as an embryo develops, the central nervous system begins as an "infolding of the outermost layer of the embryo." This layer is called the neuroectoderm.

Read more at Seeker

No comments:

Post a Comment