|

| Assorted moths in the University of Texas Insect Collection |

About 70 sturdy scales from their wings were just identified in a drilled core from northern Germany that dates to 200 million years ago. The ancestors of today's moths and butterflies therefore date to at least the latter part of the Late Triassic (251–199 million years ago).

The findings, published in the journal Science Advances, extend the origin of these insects by 5 million years, since the previous related fossil record-holders — from the United Kingdom — date to 195 million years ago. There is little doubt that dinosaurs and other iconic animals from the time saw the insects fluttering around them, just as many of us do today.

"There is definitely evidence for dinosaurs roaming around the area from outcrops further north in Sweden, which can be considered part of the same region," senior author Bas van de Schootbrugge of Utrecht University told Seeker.

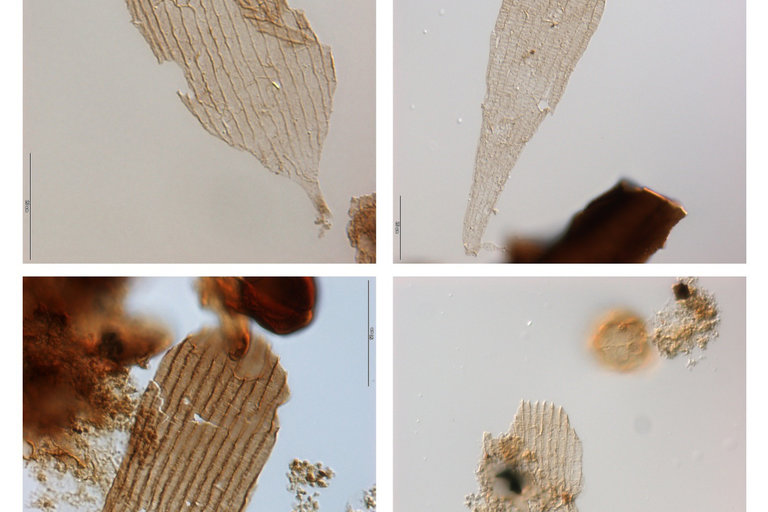

Unlike dinosaurs, moths and butterflies do not have bones that can fossilize and preserve. Their many wing scales, however, are made of chitin, which is the primary component of hard natural materials like crustacean exoskeletons and cephalopod beaks.

"The preservation of these scales does require some exceptional conditions, such as a low oxygen environment and rapid burial," van de Schootbrugge said, adding that the scales that he and his colleagues studied "were deposited in a very shallow lagoon that was oxygen depleted, which contributed to their exceptional preservation."

|

| Examples of the oldest wing and body scales of primitive moths from the Schadelah-1 core photographed with transmitted light |

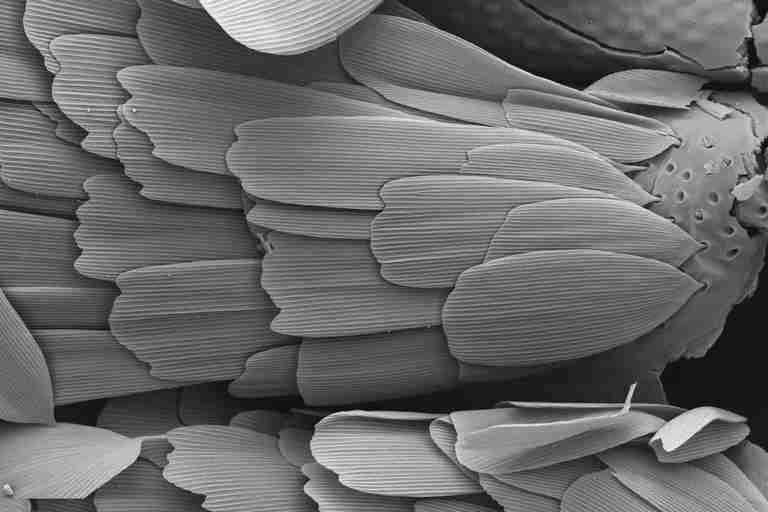

The Late Triassic scales come from insects in the order Lepidoptera, which is the second largest order in the class Insecta and includes butterflies, moths, skippers, caterpillars, borers, webworms, cankerworms, and bagworms. Technically, the Triassic scales all came from ancestral moths, since butterflies as we know them today are part of the family Papilionidae, which only emerged during the last 50 million years.

"True butterflies are therefore a relatively young group," lead author Timo van Eldijk, also of the University of Utrecht, told Seeker. "However, these butterflies evolved from moth-like ancestors. So, all butterflies are moths, but only some moths are butterflies."

The clade closest to Lepidoptera is Trichoptera that includes caddisflies. Both orders originated from a common ancestor that must have lived in the Late Triassic, and possibly even earlier. This ancestor did not have a proboscis, which is the elongated tubular, flexible mouthpart present in some moths and butterflies. Van Eldjik explained that the oldest living families of Lepidoptera, such as the Mycropterigidae, still have mandibles.

Conveniently, the more derived families with a proboscis are also distinguished by having hollow scales. Such scales were found within the Late Triassic assemblage, along with other types. Some ancestral moths therefore chewed their food, while others sucked their suppers.

Modern moths and butterflies with a proboscis sink it deep into flowers to sip nectar. This would have been impossible 200 million years ago, though, since flowers had not even evolved yet. The first known flowers in the fossil record date to about 140 million years ago.

|

| Scanning electron microscope image of the dense covering of scales on the wings and body of a Glossatan (proboscis-bearing) moth |

"We hypothesize that feeding on pollination droplets was one of the key drivers behind the evolution of the proboscis," van de Schootbrugge said.

He added that, given the diverse pollen and spore specimens found with the insect remains, there were extensive forests of large trees with an understory of ferns and related plants at the northern German site, which is near Braunschweig. In a clay pit, not far from where the core was drilled, they found the remains of many insects, such as beetles.

"So, it was an extensive coastal area covered in thick vegetation with many organisms, much like what you would expect from a coastal forest in, for example, the Mississippi delta," van de Schootbrugge said.

He and his team suspect that the Triassic ancestral moths probably varied in size, similar to today's moths and butterflies. They said that it is currently not possible to speculate on their coloring or if there were any differences between the sexes.

They do know, however, that these winged insects went through egg, caterpillar, pupa, and adult stages, just as moths and butterflies do today. This life cycle, called "complete metamorphosis," evolved much earlier than the Late Triassic and occurs in other insects, such as flies, beetles, and wasps.

The scientists observe that Lepidoptera survived many mass extinction events. The Late Triassic was itself a time of global mass extinction. This was followed by the K/T extinction event about 66 million years ago, during which non-avian dinosaurs and many species went extinct. At least some of the ancestors of moths and butterflies survived that event.

"So, they seem hardier than what you might think at first," van de Schootbrugge said. "Now, climate change might not affect insects that much, as they can adapt rapidly. They are the most successful group of organisms on land right now, and climate change might allow them to explore high-latitude regions, increasing their geographical spread."

Read more at Seeker

No comments:

Post a Comment