Scientists in Singapore proved they are worth their salt by sextupling hard drive space with no equipment upgrades.

Scientists at the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) in collaboration with National University of Singapore and the Data Storage Institute discovered that simply adding table salt to a solution used when creating hard drives increased the capacity by almost six times.

This advance means a hard drives holding 1 Terabyte (TB) of data today, in the future, could hold 6 TB of data within the same size and form factor. The salt causes this increase because it forces the bits (pieces of information on your hard drive) into predictable, organized patterns on your hard drive. A*STAR likens the system to packing your clothes in your suitcase when you travel. The neater you pack them the more you can carry." Current methods use clusters of data without such a specific organizational system.

The secret to their research lies in their salty solution. Using an existing production method the scientists discovered adding table salt would produce highly defined nanostructures without the need for expensive equipment upgrades.This ‘salty developer solution’ method was invented by Dr. Yang when he was a graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Dr. Joel Yang, the Singapore scientist who heads up the project told AFP, "It can give you a very high contrast. We are now able to see fine lines that would normally be blurred out."

Read more at Discovery News

Oct 15, 2011

New Technologies Challenge Old Ideas About Early Hominid Diets

New assessments by researchers using the latest high-tech tools to study the diets of early hominids are challenging long-held assumptions about what our ancestors ate, says a study by the University of Colorado Boulder and the University of Arkansas.

By analyzing microscopic pits and scratches on hominid teeth, as well as stable isotopes of carbon found in teeth, researchers are getting a very different picture of the diet habitats of early hominids than that painted by the physical structure of the skull, jawbones and teeth. While some early hominids sported powerful jaws and large molars -- including Paranthropus boisei, dubbed "Nutcracker Man" -- they may have cracked nuts rarely if at all, said CU-Boulder anthropology Professor Matt Sponheimer, study co-author.

Such findings are forcing anthropologists to rethink long-held assumptions about early hominids, aided by technological tools that were unknown just a few years ago. A paper on the subject by Sponheimer and co-author Peter Ungar, a distinguished professor at the University of Arkansas, was published in the Oct. 14 issue of Science.

Earlier this year, Sponheimer and his colleagues showed Paranthropus boisei was essentially feeding on grasses and sedges rather than soft fruits preferred by chimpanzees. "We can now be sure that Paranthropus boisei ate foods that no self-respecting chimpanzee would stomach in quantity," said Sponheimer. "It is also clear that our previous notions of this group's diet were grossly oversimplified at best, and absolutely backward at worst."

"The morphology tells you what a hominid may have eaten," said Ungar. But it does not necessarily reveal what the animal was actually dining on, he said.

While Ungar studies dental micro-wear -- the microscopic pits and scratches that telltale food leaves behind on teeth -- Sponheimer studies stable isotopes of carbon in teeth. By analyzing stable carbon isotopes obtained from tiny portions of animal teeth, researchers can determine whether the animals were eating foods that use different photosynthetic pathways that convert sunlight to energy.

The results for teeth from Paranthropus boisei, published earlier this year, indicated they were eating foods from the so-called C4 photosynthetic pathway, which points to consumption of grasses and sedges. The analysis stands in contrast to our closest human relatives like chimpanzees and gorillas that eat foods from the so-called C3 synthetic pathway pointing to a diet that included trees, shrubs and bushes.

Dental micro-wear and stable isotope studies also point to potentially large differences in diet between southern and eastern African hominids, said Sponheimer, a finding that was not anticipated given their strong anatomical similarities. "Frankly, I don't believe anyone would have predicted such strong regional differences," said Sponheimer. "But this is one of the things that is fun about science -- nature frequently reminds us that there is much that we don't yet understand.

"The bottom line is that our old answers about hominid diets are no longer sufficient, and we really need to start looking in directions that would have been considered crazy even a decade ago," Sponheimer said. "We also see much more evidence of dietary variability among our hominid kin than was previously appreciated. Consequently, the whole notion of hominid diet is really problematic, as different species may have consumed fundamentally different things."

Read more at Science Daily

By analyzing microscopic pits and scratches on hominid teeth, as well as stable isotopes of carbon found in teeth, researchers are getting a very different picture of the diet habitats of early hominids than that painted by the physical structure of the skull, jawbones and teeth. While some early hominids sported powerful jaws and large molars -- including Paranthropus boisei, dubbed "Nutcracker Man" -- they may have cracked nuts rarely if at all, said CU-Boulder anthropology Professor Matt Sponheimer, study co-author.

Such findings are forcing anthropologists to rethink long-held assumptions about early hominids, aided by technological tools that were unknown just a few years ago. A paper on the subject by Sponheimer and co-author Peter Ungar, a distinguished professor at the University of Arkansas, was published in the Oct. 14 issue of Science.

Earlier this year, Sponheimer and his colleagues showed Paranthropus boisei was essentially feeding on grasses and sedges rather than soft fruits preferred by chimpanzees. "We can now be sure that Paranthropus boisei ate foods that no self-respecting chimpanzee would stomach in quantity," said Sponheimer. "It is also clear that our previous notions of this group's diet were grossly oversimplified at best, and absolutely backward at worst."

"The morphology tells you what a hominid may have eaten," said Ungar. But it does not necessarily reveal what the animal was actually dining on, he said.

While Ungar studies dental micro-wear -- the microscopic pits and scratches that telltale food leaves behind on teeth -- Sponheimer studies stable isotopes of carbon in teeth. By analyzing stable carbon isotopes obtained from tiny portions of animal teeth, researchers can determine whether the animals were eating foods that use different photosynthetic pathways that convert sunlight to energy.

The results for teeth from Paranthropus boisei, published earlier this year, indicated they were eating foods from the so-called C4 photosynthetic pathway, which points to consumption of grasses and sedges. The analysis stands in contrast to our closest human relatives like chimpanzees and gorillas that eat foods from the so-called C3 synthetic pathway pointing to a diet that included trees, shrubs and bushes.

Dental micro-wear and stable isotope studies also point to potentially large differences in diet between southern and eastern African hominids, said Sponheimer, a finding that was not anticipated given their strong anatomical similarities. "Frankly, I don't believe anyone would have predicted such strong regional differences," said Sponheimer. "But this is one of the things that is fun about science -- nature frequently reminds us that there is much that we don't yet understand.

"The bottom line is that our old answers about hominid diets are no longer sufficient, and we really need to start looking in directions that would have been considered crazy even a decade ago," Sponheimer said. "We also see much more evidence of dietary variability among our hominid kin than was previously appreciated. Consequently, the whole notion of hominid diet is really problematic, as different species may have consumed fundamentally different things."

Read more at Science Daily

Oct 14, 2011

Sleights of hand, sleights of mind

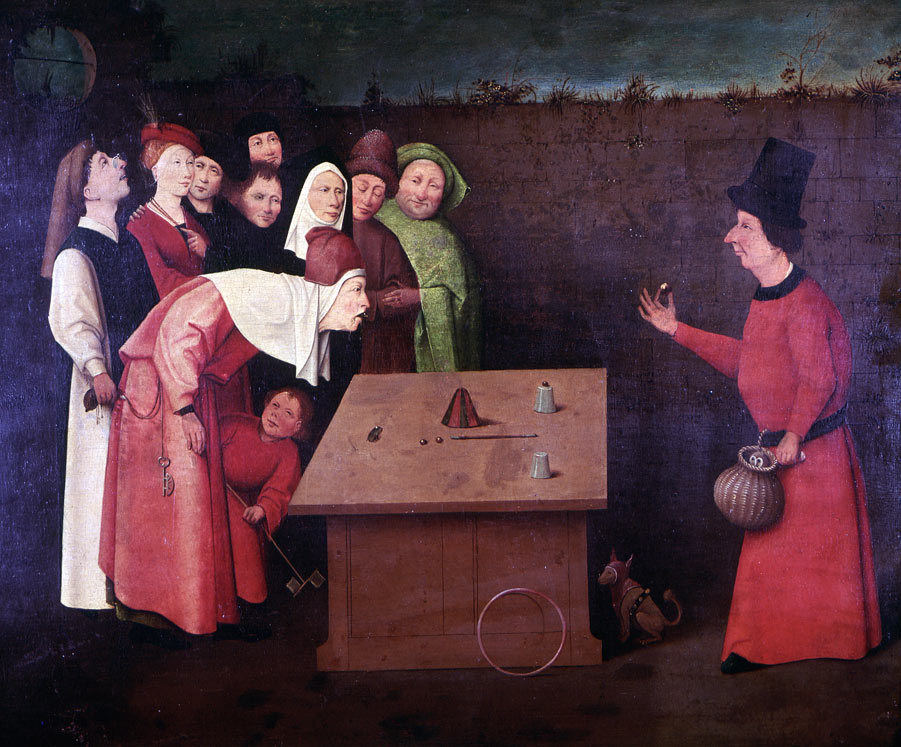

The Conjurer, by Heironymus Bosch, depicts a medieval magician performing for a small crowd, while pickpockets steal the spectators' belongings. The painting, on display at the Musée Municipal in St.-Germain-en-Laye, France, illustrates that magicians have long known how to hack into our mental processes. The principles of magic, refined and perfected over the centuries, provide neuroscientists with new ways to study the brain and could help them in their quest to reveal how the organ performs the greatest trick of all - consciousness itself.

"In principle, neuroscience and magic have little in common," says Susana Martinez-Conde, director of the Visual Neuroscience Laboratory at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Arizona. "In fact, they are hugely complementary and magicians have a lot to offer us. They can manipulate the attention and consciousness of spectators so much better than we do in the lab." A few years ago, Martinez-Conde and her husband Stephen Macknik decided to investigate exactly how magicians fool the brain so adeptly. In doing so, they founded the exciting new discipline they refer to as 'neuromagic,' which aims to "pop the hood on your brain as you are suckered in by sleights of hand."

"It all started when Stephen and I were asked to co-chair the

11th annual meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness," Martinez-Conde explains. "Traditionally, this was a very academic conference that had no impact outside the specialist field. We wanted to reach the general public as well, but we weren't sure exactly what to do."

The wife-and-husband team went to Las Vegas, where the conference was to be held. It was then, while scouting for potential conference venues, that the idea first came to them. "We saw a lot of ads for magic shows and realized that was the connection we were looking for. We contacted a number of magicians, such as Penn and Teller, James Randi, Apollo Robbins and Mac King and invited them to a special symposium [at the conference], to share their insights into what makes magic work in the mind of the spectator."

Illusions on top of illusions

Magicians have a repertoire of perhaps several dozen techniques which they use to deceive spectators and enhance perception of their tricks. One of these is 'misdirection,' which exploits inattentional blindness and change blindness, two phenomena that psychologists have studied intensively in recent years.

Studies of inattentional blindness show that focused attention can make us oblivious to sights that would otherwise be glaringly obvious, while studies of change blindness show that dramatic changes in a scene can go unnoticed if they occur during a brief interruption, even when we look directly at the scene.

Magicians take advantage of this to manipulate their spectators' attentional spotlight. They know, for example, that the eyes give off important social cues, and that people hava a natural impulse to pay attention to the objects that others are attending to. They exploit this 'joint attention' by using their eye movements to divert the audience's attention away from the 'method' – the secret action behind the trick – and towards the magical effect.

They also know that the sudden appearance of a new and unusual object will immediately draw the audience's attention. Hence, producing a flying dove gives them an opportunity to perform other hidden manoeuvres.

These cognitive illusions are used together with optical illusions that exploit the properties of light, visual illusions that exploit how the brain interprets images, special effects such as explosions and varous gimmicks, including secret devices and mechanical artifacts. (Both Martinez-Conde and Macknik have studied visual illusions extensively, and about 10 years ago they set up the hugely popular Best Illusion of the Year Contest.)

By combining these illusions, the magician bombards the audience's senses, overloading their brains with multiple tasks that cannot be processed simultaneously. In other words, magic is a 'superstimulus,' or a form of 'mental jujitsu' against which we are completely defenceless.

"Instead of isolating the specific variables and using one effect, magicians use multiple illusions," says Martinez-Conde. "They lump everything together, putting illusions on top of illusions. It's virtually impossible for spectators to penetrate these layers and get at the method of the trick."

Read more at The Guardian

"In principle, neuroscience and magic have little in common," says Susana Martinez-Conde, director of the Visual Neuroscience Laboratory at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Arizona. "In fact, they are hugely complementary and magicians have a lot to offer us. They can manipulate the attention and consciousness of spectators so much better than we do in the lab." A few years ago, Martinez-Conde and her husband Stephen Macknik decided to investigate exactly how magicians fool the brain so adeptly. In doing so, they founded the exciting new discipline they refer to as 'neuromagic,' which aims to "pop the hood on your brain as you are suckered in by sleights of hand."

"It all started when Stephen and I were asked to co-chair the

11th annual meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness," Martinez-Conde explains. "Traditionally, this was a very academic conference that had no impact outside the specialist field. We wanted to reach the general public as well, but we weren't sure exactly what to do."

The wife-and-husband team went to Las Vegas, where the conference was to be held. It was then, while scouting for potential conference venues, that the idea first came to them. "We saw a lot of ads for magic shows and realized that was the connection we were looking for. We contacted a number of magicians, such as Penn and Teller, James Randi, Apollo Robbins and Mac King and invited them to a special symposium [at the conference], to share their insights into what makes magic work in the mind of the spectator."

Illusions on top of illusions

Magicians have a repertoire of perhaps several dozen techniques which they use to deceive spectators and enhance perception of their tricks. One of these is 'misdirection,' which exploits inattentional blindness and change blindness, two phenomena that psychologists have studied intensively in recent years.

Studies of inattentional blindness show that focused attention can make us oblivious to sights that would otherwise be glaringly obvious, while studies of change blindness show that dramatic changes in a scene can go unnoticed if they occur during a brief interruption, even when we look directly at the scene.

Magicians take advantage of this to manipulate their spectators' attentional spotlight. They know, for example, that the eyes give off important social cues, and that people hava a natural impulse to pay attention to the objects that others are attending to. They exploit this 'joint attention' by using their eye movements to divert the audience's attention away from the 'method' – the secret action behind the trick – and towards the magical effect.

They also know that the sudden appearance of a new and unusual object will immediately draw the audience's attention. Hence, producing a flying dove gives them an opportunity to perform other hidden manoeuvres.

These cognitive illusions are used together with optical illusions that exploit the properties of light, visual illusions that exploit how the brain interprets images, special effects such as explosions and varous gimmicks, including secret devices and mechanical artifacts. (Both Martinez-Conde and Macknik have studied visual illusions extensively, and about 10 years ago they set up the hugely popular Best Illusion of the Year Contest.)

By combining these illusions, the magician bombards the audience's senses, overloading their brains with multiple tasks that cannot be processed simultaneously. In other words, magic is a 'superstimulus,' or a form of 'mental jujitsu' against which we are completely defenceless.

"Instead of isolating the specific variables and using one effect, magicians use multiple illusions," says Martinez-Conde. "They lump everything together, putting illusions on top of illusions. It's virtually impossible for spectators to penetrate these layers and get at the method of the trick."

Read more at The Guardian

Flesh-Eating Piranhas Bark When Angered

Hollywood has given the piranha a rough reputation as a vicious fish with a penchant for biting. But according to Sandie Millot, Pierre Vandewalle and Eric Parmentier from the University of Liège, Belgium, the piranha barks more than it bites.

The team of biologists plunged a hydrophone (an underwater microphone) into a tank of captive red-bellied piranhas and listened in to the different sounds they make in different situations.

So far, the team registered three distinct noises. When piranhas enter into a confrontation they’ll make a barking noise. When they’re fighting for food or circling an opponent, a piranha will make short percussive drum-like sounds. And when their jaws snap at each other, a softer croaking sound is produced.

They might make a noise when they’re being amorous piranhas, too, but the team would have to travel to Brazil to answer that question. “It is difficult for the fish to reproduce in the tank,” according to Parmentier.

Convinced that the fish had a wider acoustic repertoire than they had initially thought, the team looked into how the fish produce the sounds. Piranhas produce sounds by contracting muscles which vibrate their swim bladders — internal organs that regulate buoyancy.

But once those muscles are no longer contracted, the sound stopped. This means that the muscles were driving the swim bladder’s vibration directly, and not through the bladder’s own intrinsic resonant properties.

Read more at Wired Science

The team of biologists plunged a hydrophone (an underwater microphone) into a tank of captive red-bellied piranhas and listened in to the different sounds they make in different situations.

So far, the team registered three distinct noises. When piranhas enter into a confrontation they’ll make a barking noise. When they’re fighting for food or circling an opponent, a piranha will make short percussive drum-like sounds. And when their jaws snap at each other, a softer croaking sound is produced.

They might make a noise when they’re being amorous piranhas, too, but the team would have to travel to Brazil to answer that question. “It is difficult for the fish to reproduce in the tank,” according to Parmentier.

Convinced that the fish had a wider acoustic repertoire than they had initially thought, the team looked into how the fish produce the sounds. Piranhas produce sounds by contracting muscles which vibrate their swim bladders — internal organs that regulate buoyancy.

But once those muscles are no longer contracted, the sound stopped. This means that the muscles were driving the swim bladder’s vibration directly, and not through the bladder’s own intrinsic resonant properties.

Read more at Wired Science

T. Rex Teens Packed on the Pounds

Johnny Cash might have said, life wasn't easy for a dinosaur named SUE. She grew up quick and she grew up mean, packing on nearly 4000 pounds a year as a teenager.

"We estimate they [Tyrannosaurs] grew as fast as 3,950 pounds per year (1790 kg) during the teenage period of growth, which is more than twice the previous estimate," said John R. Hutchinson of The Royal Veterinary College, London in a press release.

Modeling the teenage growth spurts of an ancient mega-predator was made possible by comparing computer models of smaller, younger Tyrannosaurs with those of full grown adults, including the tyrant lizard queen, SUE, the largest T. rex skeleton yet discovered.

The new models also found that the 42 foot-long SUE may have been much heavier than earlier estimates. She tipped the scales at approximately 9 tons, according to the computer model.

"We knew she was big but the 30 percent increase in her weight was unexpected," said co-author Peter Makovicky, curator of dinosaurs at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

Hutchinson, Makovicky and a team of researchers used 3-D scans of five mounted T. rex skeletons to create computer models of the long dead predators. The computer models allowed them to estimate the weights of the dinosaurs in a range of health conditions, from dinos on diets to tubby Tyrannosaurs.

"These models range from the severely undernourished through the overly obese, but they are purposely chosen extremes that bound biologically realistic values" says study co-author Vivian Allen of the Royal Veterinary College.

"The real advantage to our method is that the models can be adjusted to accommodate the variation that is inherent in nature, so we don't have to pick an arbitrary result, but rather deal with more meaningful ranges of results," added co-author Karl T. Bates of the University of Liverpool.

Reconstructing the Cretaceous era killers using scans of mounted skeletons improved on earlier methods of estimating dino weights.

"Previous methods for calculating mass relied on scale models, which can magnify even minor errors, or on extrapolations from living animals with very different body plans from dinosaurs. We overcame such problems by using the actual skeletons as a starting point for our study," Makovicky said.

The reconstruction of SUE's skeleton may have been a bit different than she was in life, but Makovicky doesn't think this threw off their calculations.

"SUE's vertebrae were compressed by 65 million years of fossilization, which forced a more barrel-chested reconstruction" says Makovicky.

"Nine tons is the minimum estimate we arrived at using a very skinny body form, so even if we made the chest smaller, adding a more realistic amount of flesh would make up for the weight," Makovicky said.

Read more at Discovery News

"We estimate they [Tyrannosaurs] grew as fast as 3,950 pounds per year (1790 kg) during the teenage period of growth, which is more than twice the previous estimate," said John R. Hutchinson of The Royal Veterinary College, London in a press release.

Modeling the teenage growth spurts of an ancient mega-predator was made possible by comparing computer models of smaller, younger Tyrannosaurs with those of full grown adults, including the tyrant lizard queen, SUE, the largest T. rex skeleton yet discovered.

The new models also found that the 42 foot-long SUE may have been much heavier than earlier estimates. She tipped the scales at approximately 9 tons, according to the computer model.

"We knew she was big but the 30 percent increase in her weight was unexpected," said co-author Peter Makovicky, curator of dinosaurs at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

Hutchinson, Makovicky and a team of researchers used 3-D scans of five mounted T. rex skeletons to create computer models of the long dead predators. The computer models allowed them to estimate the weights of the dinosaurs in a range of health conditions, from dinos on diets to tubby Tyrannosaurs.

"These models range from the severely undernourished through the overly obese, but they are purposely chosen extremes that bound biologically realistic values" says study co-author Vivian Allen of the Royal Veterinary College.

"The real advantage to our method is that the models can be adjusted to accommodate the variation that is inherent in nature, so we don't have to pick an arbitrary result, but rather deal with more meaningful ranges of results," added co-author Karl T. Bates of the University of Liverpool.

Reconstructing the Cretaceous era killers using scans of mounted skeletons improved on earlier methods of estimating dino weights.

"Previous methods for calculating mass relied on scale models, which can magnify even minor errors, or on extrapolations from living animals with very different body plans from dinosaurs. We overcame such problems by using the actual skeletons as a starting point for our study," Makovicky said.

The reconstruction of SUE's skeleton may have been a bit different than she was in life, but Makovicky doesn't think this threw off their calculations.

"SUE's vertebrae were compressed by 65 million years of fossilization, which forced a more barrel-chested reconstruction" says Makovicky.

"Nine tons is the minimum estimate we arrived at using a very skinny body form, so even if we made the chest smaller, adding a more realistic amount of flesh would make up for the weight," Makovicky said.

Read more at Discovery News

Mystery Behind Virgin Births Explained

An eastern diamond rattlesnake recently gave successful birth five years after mating, according to a new paper that describes this longest known instance of sperm storage, outside of insects, in the animal kingdom.

The study, published in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, also presents the first documented virgin birth by a copperhead snake. In this case, the female never mated, proving that snakes and certain other animals can either give true virgin -- dadless -- birth, or may store sperm for long periods.

Actual mate-less virgin birthing, known as parthenogenesis, "has now been observed to occur naturally within all lineages of jawed vertebrates, with the exception of mammals," co-author Warren Booth told Discovery News. "We have recently seen genetic confirmation in species such as boa constrictors, rainbow boas, various shark species, Komodo dragons, and domestic turkeys, to name a few.

Booth, an integrative molecular ecologist at North Carolina State University, analyzed DNA from the female copperhead that had been on exhibit -- without a mate -- for years at the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher. Molecular DNA fingerprinting excluded the contribution of a male in her giving birth, which produced a litter of four normal-looking offspring.

The eastern diamond-backed rattlesnake's birthing moment was even more dramatic, as she suddenly produced 19 very healthy offspring consisting of 10 females and nine males. DNA analysis confirmed that the 19 babies have a dad.

"This snake was caught when it was around one year old, and therefore would be considered sexually immature," said Booth, who co-authored the paper with Gordon Schuett of Georgia State University. "It was housed in isolation from males up to the time that it gave birth. Therefore, this snake was mated in the wild as a sexually immature juvenile."

He and Schuett said internal sperm storage tubules or an ability to twist a portion of the uterus might explain how the rattlesnake stored sperm for five years. To manage the second trick, Booth said "a region of the uterus becomes convoluted and contracted, which may act as a plug sequestering the sperm until ovulation."

Fish, birds, amphibians, insects and other reptiles can also store sperm for long periods.

Mammals are less successful, but a recent study on the Greater Asiatic Yellow House Bat found that females of this species could store sperm for several months. In contrast, women can store it for just hours or days.

Women are incapable of giving true virgin birth since certain genes must come from the man as well as the woman. Schuett explained that, in laboratory settings, scientists have gotten around this requirement for mammals by creating parthenogenic mice.

Both types of unusual birthing, true virginal and long-term sperm storage, have drawbacks and benefits. Storing sperm allows females to overcome climate challenges and other obstacles. Giving virgin birth may hurt genetic diversity and yield only all-female or all-male progeny. On the other hand, it could also weed out mutations that can make individuals less fit.

Read more at Discovery News

The study, published in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, also presents the first documented virgin birth by a copperhead snake. In this case, the female never mated, proving that snakes and certain other animals can either give true virgin -- dadless -- birth, or may store sperm for long periods.

Actual mate-less virgin birthing, known as parthenogenesis, "has now been observed to occur naturally within all lineages of jawed vertebrates, with the exception of mammals," co-author Warren Booth told Discovery News. "We have recently seen genetic confirmation in species such as boa constrictors, rainbow boas, various shark species, Komodo dragons, and domestic turkeys, to name a few.

Booth, an integrative molecular ecologist at North Carolina State University, analyzed DNA from the female copperhead that had been on exhibit -- without a mate -- for years at the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher. Molecular DNA fingerprinting excluded the contribution of a male in her giving birth, which produced a litter of four normal-looking offspring.

The eastern diamond-backed rattlesnake's birthing moment was even more dramatic, as she suddenly produced 19 very healthy offspring consisting of 10 females and nine males. DNA analysis confirmed that the 19 babies have a dad.

"This snake was caught when it was around one year old, and therefore would be considered sexually immature," said Booth, who co-authored the paper with Gordon Schuett of Georgia State University. "It was housed in isolation from males up to the time that it gave birth. Therefore, this snake was mated in the wild as a sexually immature juvenile."

He and Schuett said internal sperm storage tubules or an ability to twist a portion of the uterus might explain how the rattlesnake stored sperm for five years. To manage the second trick, Booth said "a region of the uterus becomes convoluted and contracted, which may act as a plug sequestering the sperm until ovulation."

Fish, birds, amphibians, insects and other reptiles can also store sperm for long periods.

Mammals are less successful, but a recent study on the Greater Asiatic Yellow House Bat found that females of this species could store sperm for several months. In contrast, women can store it for just hours or days.

Women are incapable of giving true virgin birth since certain genes must come from the man as well as the woman. Schuett explained that, in laboratory settings, scientists have gotten around this requirement for mammals by creating parthenogenic mice.

Both types of unusual birthing, true virginal and long-term sperm storage, have drawbacks and benefits. Storing sperm allows females to overcome climate challenges and other obstacles. Giving virgin birth may hurt genetic diversity and yield only all-female or all-male progeny. On the other hand, it could also weed out mutations that can make individuals less fit.

Read more at Discovery News

Bible's Authors Decoded by Computer

A group of Israeli researchers has built a computer algorithm to decode one of the most important books in Western culture: the Bible.

The results accord generally with the consensus of scholars that the book contains writing styles defined as "priestly" and "non-priestly."

The scientists developed an algorithm able to analyze the the writing styles found in different parts of the "five books of Moses," or Pentateuch, that is Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy.

The algorithm compared sets of synonyms (called synsets) in blocks of text, along with "function" words, such as prepositions. It then looked at the distribution of the most common words in the Bible. By finding sets that were similar in any two blocks, it was able to group them according to the style they were written in.

The synonyms were identified using Hebrew roots that were translated the same way in the King James version, based largely on the work of the 19th century scholar James Strong.

Computer scientist Moshe Koppel of Bar-Ilan University, a member of the team that developed the algorithm, noted one interesting result: the synonyms for "God" weren't that important. "Some of the (synonyms) that do the heavy lifting on the Pentateuch had been noted before by scholars, but the most famous synset -- names of God -- actually didn't help at all."

That may sound counter intuitive, but Koppel said there are about 150 different sets, so the fact that a word of historical significance doesn't help determine authorship isn't that shocking.

To test out the algorithm, the researchers used it to analyze two well-known books of the Bible, Jeremiah and Ezekiel, who scholars agree had two different authors. They cut the text up and mixed them together at random. The algorithm managed to separate the two with near 99 percent accuracy, demonstrating that the method worked.

Koppel stressed that the algorithm can't say exactly how many authors the Bible has (or doesn't have). But it can say where styles change. That alone can shed light on debates over authorship. Generally speaking current scholarship divides the Pentateuch into two writing styles: priestly and non-priestly. The algorithm in most areas divided the text the same way, so that would seem to show that the division is valid.

Read more at Discovery News

The results accord generally with the consensus of scholars that the book contains writing styles defined as "priestly" and "non-priestly."

The scientists developed an algorithm able to analyze the the writing styles found in different parts of the "five books of Moses," or Pentateuch, that is Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy.

The algorithm compared sets of synonyms (called synsets) in blocks of text, along with "function" words, such as prepositions. It then looked at the distribution of the most common words in the Bible. By finding sets that were similar in any two blocks, it was able to group them according to the style they were written in.

The synonyms were identified using Hebrew roots that were translated the same way in the King James version, based largely on the work of the 19th century scholar James Strong.

Computer scientist Moshe Koppel of Bar-Ilan University, a member of the team that developed the algorithm, noted one interesting result: the synonyms for "God" weren't that important. "Some of the (synonyms) that do the heavy lifting on the Pentateuch had been noted before by scholars, but the most famous synset -- names of God -- actually didn't help at all."

That may sound counter intuitive, but Koppel said there are about 150 different sets, so the fact that a word of historical significance doesn't help determine authorship isn't that shocking.

To test out the algorithm, the researchers used it to analyze two well-known books of the Bible, Jeremiah and Ezekiel, who scholars agree had two different authors. They cut the text up and mixed them together at random. The algorithm managed to separate the two with near 99 percent accuracy, demonstrating that the method worked.

Koppel stressed that the algorithm can't say exactly how many authors the Bible has (or doesn't have). But it can say where styles change. That alone can shed light on debates over authorship. Generally speaking current scholarship divides the Pentateuch into two writing styles: priestly and non-priestly. The algorithm in most areas divided the text the same way, so that would seem to show that the division is valid.

Read more at Discovery News

Oct 13, 2011

The Divide in Your Nose

Our nose is organized and hardwired to separate the stinky from the fragrant, says new research.

Long viewed as disorganized, with receptors of all different kinds mushed up against each other, this new study suggests something entirely different.

The smell receptors lining the inside of the nose are not scattered at random, but rather are organized by how pleasant or repulsive we feel about certain smells. Receptors for smells that repel us tend to cluster together and the same goes for smells we like.

"The best organization we could find for the organization was the perception of odorant pleasantness," said Noam Sobel of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, who led the new study, published in Nature Neuroscience.

Not only are smell receptors arranged in patches, research shows, but the patches are organized along an axis of yucky to pleasant.

These findings across the senses show that we begin to organize our sensory world even at the first instant where the stimulus encounters the body. "The earliest stage of perception is already organized to match the perceptual world," Sobel said.

For smells, Sobel explained, odor pleasantness is related to the structure of the molecules that we smell. "Molecules that are small and dense tend to be unpleasant," Sobel said. "Molecules that are large and floppy tend to be pleasant. There is a correspondence between the principle axis of structure and pleasantness."

This all means that our smell preferences are, to some extent, hardwired.

"Newborns have odor preferences straight up," Sobel said. Lab rats bred in captivity for 1000 generations still have a fear response to fox odor, he added.

Researchers previously thought that smell receptors were randomly and uniformly spread over the nasal epithelium, the surface high up inside the nose that detects smells, said Sobel.

He and his team used specialized electrical probes extending almost three inches up into the nasal cavity to monitor neural signals from particular smell receptors as subjects smelled in real time.

Read more at Discovery News

Long viewed as disorganized, with receptors of all different kinds mushed up against each other, this new study suggests something entirely different.

The smell receptors lining the inside of the nose are not scattered at random, but rather are organized by how pleasant or repulsive we feel about certain smells. Receptors for smells that repel us tend to cluster together and the same goes for smells we like.

"The best organization we could find for the organization was the perception of odorant pleasantness," said Noam Sobel of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, who led the new study, published in Nature Neuroscience.

Not only are smell receptors arranged in patches, research shows, but the patches are organized along an axis of yucky to pleasant.

These findings across the senses show that we begin to organize our sensory world even at the first instant where the stimulus encounters the body. "The earliest stage of perception is already organized to match the perceptual world," Sobel said.

For smells, Sobel explained, odor pleasantness is related to the structure of the molecules that we smell. "Molecules that are small and dense tend to be unpleasant," Sobel said. "Molecules that are large and floppy tend to be pleasant. There is a correspondence between the principle axis of structure and pleasantness."

This all means that our smell preferences are, to some extent, hardwired.

"Newborns have odor preferences straight up," Sobel said. Lab rats bred in captivity for 1000 generations still have a fear response to fox odor, he added.

Researchers previously thought that smell receptors were randomly and uniformly spread over the nasal epithelium, the surface high up inside the nose that detects smells, said Sobel.

He and his team used specialized electrical probes extending almost three inches up into the nasal cavity to monitor neural signals from particular smell receptors as subjects smelled in real time.

Read more at Discovery News

Oldest Human Paint-Making Studio Discovered in Cave

A group of Home sapiens came across a picturesque cave on the coast of South Africa around 100,000 years ago. They unloaded their gear and set to work, grinding iron-rich dirt and mixing it gently with heated bone in abalone shells to create a red, paint-like mixture. Then they dipped a thin bone into the mixture to transfer it somewhere before leaving the cave — and their toolkits — behind.

Researchers now have uncovered those paint-making kits, sitting in the cave in a layer of dune sand, just where they had been left 100,000 years ago. The find is the oldest-known example of a human-made compound mixture, said study researcher Christopher Henshilwood, an archaeologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. It's also the first known example of the use of a container anywhere in the world, 40,000 years older than the next example, Henshilwood told LiveScience.

"To me, it's an important indicator of how technologically advanced people were 100,000 years ago," Henshilwood said. "If this was a paint, it also indicates the likelihood that people were using substances in a symbolic way 100,000 years ago."

Along with the toolkits, Henshilwood said, the archaeology team found pieces of ocher, or colored clay, etched with abstract designs.

An exciting find

Reporting their results Oct. 14 in the journal Science, the researchers paint a picture of a small band of hunter-gatherers who spent very little time, perhaps a day or two, in the seaside cave 186 miles (300 kilometers) east of Cape Town.

This cave, now known as Blombos Cave, has been under excavation since 1992. The cave clearly was used as a shelter for tens of thousands of years of human history, with younger rock layers yielding evidence of cooking fires and food remains. [Read: 8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

"The layer directly above this one" — the one where the paint-making toolkits would be uncovered — "was filled with shellfish and food remains, including bones and fireplaces," Henshilwood said. "But this particular layer seemed to be mainly beach sand or dune sand. And then we spotted two abalone shells." [See images of the ancient cave studio]

After three days of painstaking excavation, the archaeologists saw one of the shells was coated with a red substance.

"We immediately got very excited," Henshilwood said.

The coating turned out to be a compound made with ocher, a soft, iron-rich clay used in the earliest forms of paint and pigment. Ocher pigments may have been used to decorate the body or clothing during the middle stone ages, but the mixture also may have served as an adhesive — perhaps for attaching stone tools to handles.

Lyn Wadley, an archaeologist at the University of the Witwatersrand, told LiveScience in an email: "Since ocher-rich compounds have several potential applications, it is necessary to conduct experiments to test the effectiveness of the ancient recipe as paint, adhesive or another product."

"My own experimental work suggests that the mixture would be an effective adhesive, but I have not used the specific combination of constituents found at Blombos," added Wadley, who was not involved in the find.

Read more at Live Science

Researchers now have uncovered those paint-making kits, sitting in the cave in a layer of dune sand, just where they had been left 100,000 years ago. The find is the oldest-known example of a human-made compound mixture, said study researcher Christopher Henshilwood, an archaeologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. It's also the first known example of the use of a container anywhere in the world, 40,000 years older than the next example, Henshilwood told LiveScience.

"To me, it's an important indicator of how technologically advanced people were 100,000 years ago," Henshilwood said. "If this was a paint, it also indicates the likelihood that people were using substances in a symbolic way 100,000 years ago."

Along with the toolkits, Henshilwood said, the archaeology team found pieces of ocher, or colored clay, etched with abstract designs.

An exciting find

Reporting their results Oct. 14 in the journal Science, the researchers paint a picture of a small band of hunter-gatherers who spent very little time, perhaps a day or two, in the seaside cave 186 miles (300 kilometers) east of Cape Town.

This cave, now known as Blombos Cave, has been under excavation since 1992. The cave clearly was used as a shelter for tens of thousands of years of human history, with younger rock layers yielding evidence of cooking fires and food remains. [Read: 8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

"The layer directly above this one" — the one where the paint-making toolkits would be uncovered — "was filled with shellfish and food remains, including bones and fireplaces," Henshilwood said. "But this particular layer seemed to be mainly beach sand or dune sand. And then we spotted two abalone shells." [See images of the ancient cave studio]

After three days of painstaking excavation, the archaeologists saw one of the shells was coated with a red substance.

"We immediately got very excited," Henshilwood said.

The coating turned out to be a compound made with ocher, a soft, iron-rich clay used in the earliest forms of paint and pigment. Ocher pigments may have been used to decorate the body or clothing during the middle stone ages, but the mixture also may have served as an adhesive — perhaps for attaching stone tools to handles.

Lyn Wadley, an archaeologist at the University of the Witwatersrand, told LiveScience in an email: "Since ocher-rich compounds have several potential applications, it is necessary to conduct experiments to test the effectiveness of the ancient recipe as paint, adhesive or another product."

"My own experimental work suggests that the mixture would be an effective adhesive, but I have not used the specific combination of constituents found at Blombos," added Wadley, who was not involved in the find.

Read more at Live Science

DNA Could ID Serial Killer's Victims

Chicago-area detectives are using DNA evidence to determine the identities of eight young men murdered decades ago.

The eight were victims of John Wayne Gacy, who was convicted of murdering 33 boys and young men between 1972 and 1978. He was known as the “Killer Clown” because he would dress as one for charity events. Gacy was executed in Illinois in 1994.

Although 25 of his victims were identified, eight have remained anonymous until today. Now the Cook County Sheriff’s Department wants to use DNA techniques unavailable in the 1970s to identify them.

When the murders originally occurred, the only way to identify a body was via fingerprints or dental records. The unidentified bodies were all of men in their late teens and early 20s, but officials had no dental or fingerprint records and so it was impossible to say who the men were.

Just in case dental records came to light, the pathologists at the time removed the upper and lower jawbones of the unidentified victims. Those bones were buried in 2009. Last week, investigators obtained a court order to exhume the jawbones and analyze the DNA. Of the eight remains, four contained enough material that could be successfully analyzed, but the other four could not. So detectives had to locate the graves where the bodies had been buried and exhume more remains, in those cases femurs and vertebrae.

The DNA used to identify the bodies is nuclear DNA, which is contributed by both parents. That means a match can be made with even a relatively distant relative, such as a cousin. But it still means a relative has to offer a sample to compare. The sherrif's office is asking anyone who reported a relative missing in the 1970s to come forward in the hopes that they get a match.

Read more at Discovery News

The eight were victims of John Wayne Gacy, who was convicted of murdering 33 boys and young men between 1972 and 1978. He was known as the “Killer Clown” because he would dress as one for charity events. Gacy was executed in Illinois in 1994.

Although 25 of his victims were identified, eight have remained anonymous until today. Now the Cook County Sheriff’s Department wants to use DNA techniques unavailable in the 1970s to identify them.

When the murders originally occurred, the only way to identify a body was via fingerprints or dental records. The unidentified bodies were all of men in their late teens and early 20s, but officials had no dental or fingerprint records and so it was impossible to say who the men were.

Just in case dental records came to light, the pathologists at the time removed the upper and lower jawbones of the unidentified victims. Those bones were buried in 2009. Last week, investigators obtained a court order to exhume the jawbones and analyze the DNA. Of the eight remains, four contained enough material that could be successfully analyzed, but the other four could not. So detectives had to locate the graves where the bodies had been buried and exhume more remains, in those cases femurs and vertebrae.

The DNA used to identify the bodies is nuclear DNA, which is contributed by both parents. That means a match can be made with even a relatively distant relative, such as a cousin. But it still means a relative has to offer a sample to compare. The sherrif's office is asking anyone who reported a relative missing in the 1970s to come forward in the hopes that they get a match.

Read more at Discovery News

Is This the First Self-Portrait of Michelangelo?

A unique marble relief might be the first known self-portrait of Michelangelo, Italian art historians have announced this week.

Belonging to a private collection, the sculpture is a white marble tondo, or circle, about 14 inches in diameter. It depicts a bearded head in three-quarter profile.

"It's a very high-quality sculpture, carved with precision and delicacy. It certainly deserves much attention," Alessandro Vezzosi, director of the Museo Ideale in the Tuscan town of Vinci, told Discovery News.

The carving was identified as a possible work by Michelangelo back in 1999 by the late James Beck, professor of art history at Columbia University.

In his monograph "The Three Worlds of Michelangelo," Beck called the artwork a "possible Michelangelo self portrait" and dated it to about 1545.

At that time, 70-year-old Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) had already completed masterpieces such as the David, the Pieta in the Basilica of St. Peter, the Medici chapels in Florence and the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel.

According to Beck, there was no doubt that the carved face of the old bearded man belonged to Michelangelo.

"It is the only portrait of Michelangelo in marble and in relief that I am aware of from his lifetime," Beck told Discovery News in an interview prior to his death in 2007.

Since Beck's attribution, interest in the tondo increased, and in 2005 the owners, a noble Tuscan family, accepted to briefly exhibit it at the Museo Ideale.

Six years later, the sculpture went on a temporary display (until the end of the month) at a museum in Caprese, Michelangelo's birthplace near Arezzo.

Following further research, another leading art historian, Claudio Strinati, general director of the Italian Ministry of Culture, backed up Beck's attribution.

"I find his hypothesis plausible. It is a portrait of Michelangelo or even a self portrait," Strinati said.

Indeed, the sculpture is consistent with known portraits of the Renaissance master, such as paintings by Giuliano Bugiardini and Jacopino del Conte, kept at the Casa Buonarroti museum in Florence, and bronzes by Daniele da Volterra, on display at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England.

"My idea is that the portrait was conceived by Michelangelo when he worked on the tomb of Pope Julius II," Strinati said.

In 1505, Julius II (1443 – 1513) commissioned Michelangelo to execute his tomb. A work of massive proportions, it was expected to feature the greatest statuary the world had ever seen.

Intended to display forty life-size statues on a three-level structure, the tomb was never finished as the pope decided to suspend the work, instead assigning Michelangelo the job of painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Nevertheless, Michelangelo worked on the tomb project intermittently for 40 years, between 1505 and 1545, well after the death of the pope who was entombed in St. Peter's Basilica in 1513.

Progressively downscaled, the project, which caused the artist much anguish, was finally set up in San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome in the form of a wall tomb.

It incorporated some of Michelangelo's sculpture, including the imposing figure of Moses.

According to Strinati, it is possible that the carved tondo was created as one of the sculptures which would have adorned the tomb.

Analysis carried by Corrado Gratziu and Alessandra Moscato at Pisa University, revealed that the marble used for the tondo came from Carrara in north-west Tuscany, more precisely from the Polvaccio quarry.

"Indeed, it is the same marble used for Julius II's tomb," Strinati said.

Read more at Discovery News

Belonging to a private collection, the sculpture is a white marble tondo, or circle, about 14 inches in diameter. It depicts a bearded head in three-quarter profile.

"It's a very high-quality sculpture, carved with precision and delicacy. It certainly deserves much attention," Alessandro Vezzosi, director of the Museo Ideale in the Tuscan town of Vinci, told Discovery News.

The carving was identified as a possible work by Michelangelo back in 1999 by the late James Beck, professor of art history at Columbia University.

In his monograph "The Three Worlds of Michelangelo," Beck called the artwork a "possible Michelangelo self portrait" and dated it to about 1545.

At that time, 70-year-old Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) had already completed masterpieces such as the David, the Pieta in the Basilica of St. Peter, the Medici chapels in Florence and the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel.

According to Beck, there was no doubt that the carved face of the old bearded man belonged to Michelangelo.

"It is the only portrait of Michelangelo in marble and in relief that I am aware of from his lifetime," Beck told Discovery News in an interview prior to his death in 2007.

Since Beck's attribution, interest in the tondo increased, and in 2005 the owners, a noble Tuscan family, accepted to briefly exhibit it at the Museo Ideale.

Six years later, the sculpture went on a temporary display (until the end of the month) at a museum in Caprese, Michelangelo's birthplace near Arezzo.

Following further research, another leading art historian, Claudio Strinati, general director of the Italian Ministry of Culture, backed up Beck's attribution.

"I find his hypothesis plausible. It is a portrait of Michelangelo or even a self portrait," Strinati said.

Indeed, the sculpture is consistent with known portraits of the Renaissance master, such as paintings by Giuliano Bugiardini and Jacopino del Conte, kept at the Casa Buonarroti museum in Florence, and bronzes by Daniele da Volterra, on display at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England.

"My idea is that the portrait was conceived by Michelangelo when he worked on the tomb of Pope Julius II," Strinati said.

In 1505, Julius II (1443 – 1513) commissioned Michelangelo to execute his tomb. A work of massive proportions, it was expected to feature the greatest statuary the world had ever seen.

Intended to display forty life-size statues on a three-level structure, the tomb was never finished as the pope decided to suspend the work, instead assigning Michelangelo the job of painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Nevertheless, Michelangelo worked on the tomb project intermittently for 40 years, between 1505 and 1545, well after the death of the pope who was entombed in St. Peter's Basilica in 1513.

Progressively downscaled, the project, which caused the artist much anguish, was finally set up in San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome in the form of a wall tomb.

It incorporated some of Michelangelo's sculpture, including the imposing figure of Moses.

According to Strinati, it is possible that the carved tondo was created as one of the sculptures which would have adorned the tomb.

Analysis carried by Corrado Gratziu and Alessandra Moscato at Pisa University, revealed that the marble used for the tondo came from Carrara in north-west Tuscany, more precisely from the Polvaccio quarry.

"Indeed, it is the same marble used for Julius II's tomb," Strinati said.

Read more at Discovery News

Oct 12, 2011

Evolutionary Comparison Finds Shocking History for Vertebrates

Evolutionary biologists from Cornell University have discovered that just about every vertebrate on Earth — including humans — descended from an ancient ancestor with a sixth sense: the ability to detect electrical fields in water.

About 500 million years ago there was probably a predatory marine fish with good eyesight, powerful jaws and sharp teeth roaming the oceans, sporting a lateral line system for detecting water movements and a well-developed electroreceptive system to sense predators and prey around it. The vast majority of the 65,000 or so living vertebrate species are its descendants.

A few hundred million years ago, there was a major fork in the evolutionary tree. One lineage led to the ray-finned fishes, or actinopterygians, and they’ve kept a weak electroreceptive system to this day. Sturgeon have receptors in the skin of their heads, for example, and the North American paddlefish has 70,000 receptors in its snout and head.

The other lineage led to lobe-finned fishes, or sarcopterygians, which in turn gave rise to land vertebrates. Some land vertebrates, including salamanders like the Mexican axolotl, still have electroreception. But in the change to terrestrial life, the lineage leading to reptiles, birds and mammals lost that electrosense and the lateral line.

The researchers took the axolotl (to represent the evolutionary lineage leading to land animals) and the paddlefish (as a model for the branch leading to ray-finned fishes) to find out the history of this sense. They found that electrosensors develop in precisely the same pattern from the same embryonic tissue in the developing skin, confirming that this is an ancient sensory system.

Also, the electrosensory organs develop immediately adjacent to the lateral line, providing compelling evidence “that these two sensory systems share a common evolutionary heritage,” said Willy Bemis, Cornell professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and a senior author of the paper.

Read more at Wired Science

About 500 million years ago there was probably a predatory marine fish with good eyesight, powerful jaws and sharp teeth roaming the oceans, sporting a lateral line system for detecting water movements and a well-developed electroreceptive system to sense predators and prey around it. The vast majority of the 65,000 or so living vertebrate species are its descendants.

A few hundred million years ago, there was a major fork in the evolutionary tree. One lineage led to the ray-finned fishes, or actinopterygians, and they’ve kept a weak electroreceptive system to this day. Sturgeon have receptors in the skin of their heads, for example, and the North American paddlefish has 70,000 receptors in its snout and head.

The other lineage led to lobe-finned fishes, or sarcopterygians, which in turn gave rise to land vertebrates. Some land vertebrates, including salamanders like the Mexican axolotl, still have electroreception. But in the change to terrestrial life, the lineage leading to reptiles, birds and mammals lost that electrosense and the lateral line.

The researchers took the axolotl (to represent the evolutionary lineage leading to land animals) and the paddlefish (as a model for the branch leading to ray-finned fishes) to find out the history of this sense. They found that electrosensors develop in precisely the same pattern from the same embryonic tissue in the developing skin, confirming that this is an ancient sensory system.

Also, the electrosensory organs develop immediately adjacent to the lateral line, providing compelling evidence “that these two sensory systems share a common evolutionary heritage,” said Willy Bemis, Cornell professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and a senior author of the paper.

Read more at Wired Science

Why the Black Death Was the Mother of All Plagues

Plague germs teased from mediaeval cadavers in a London cemetery have shed light on why the bacterium that unleashed the Black Death was so lethal and spawned later waves of epidemics.

The DNA of Yersinia pestis shows, in evolutionary terms, a highly successful germ to which the population of 14th-century Europe had no immune defences, according to a study published Wednesday in the British journal Nature.

It also lays bare a pathogen that has undergone no major genetic change over six centuries.

"The Black Death was the first plague pandemic in human history," said Johannes Krause, lead researcher and a professor at the University of Tuebingen, Germany.

"Humans were (immunologically) naive and not adapted to this disease," he said in an email exchange.

No bug or virus has wiped out a greater proportion of humankind in a single epidemic than the Black Death.

Brought to Europe from China, it scythed through the continent from 1347 to 1351, killing about 30 million people -- about one in three of Europe's and nearly one in 12 of the world's population at the time.

Remarkably, more recent variants of the bacterium hardly vary compared to the original microbe, says the paper.

"Based on the reconstructed genome, we can say that the mediaeval plague is close to the root of all modern human pathogenic plague strains," said Krause.

"The ancient plague strain does not carry a single position that cannot be found in the same state in modern strains."

This deep similarity between ancient and modern plague calls into question the long-held assumption that virulence-enhancing mutations are what made Y. pestis so deadly to the Middle Ages.

Like Native American Indians who were exposed to smallpox, Europeans had never been exposed to the bacterium, said Krause.

"Plague was among the strongest sources of selection on the human population in the last few thousand years," he added. "People who were less susceptible due to mutations might have survived, and these (beneficial) mutations may have spread."

Another likely factor that worsened the Black Death's toll was social conditions, which were far worse compared to the 18th or 19th centuries. Poverty and malnutrition were rampant, and even the concept of hygiene was non-existent.

The onset of the so-called "Little Ice Age" could also have favoured the spread of the disease which, like many pathogens, travels more quickly in cold climes.

The same goes for the rats that carried the blood-sucking insects -- fleas or lice, perhaps both -- that transmit the disease.

Indeed, the species of rodent, Ratus ratus, that sowed terror across a continent in the 14th century is not the same as the one that transports plague today, Ratus norvegicus, Krause said.

The 1918-19 Spanish flu pandemic killed by some estimates 50 million people. In absolute terms, this was the deadliest pandemic in human history.

But with a world population that was close to two billion, the toll in relative terms was far smaller than that of the Black Death, when the number of humans was in the hundreds of millions.

Read more at Discovery News

The DNA of Yersinia pestis shows, in evolutionary terms, a highly successful germ to which the population of 14th-century Europe had no immune defences, according to a study published Wednesday in the British journal Nature.

It also lays bare a pathogen that has undergone no major genetic change over six centuries.

"The Black Death was the first plague pandemic in human history," said Johannes Krause, lead researcher and a professor at the University of Tuebingen, Germany.

"Humans were (immunologically) naive and not adapted to this disease," he said in an email exchange.

No bug or virus has wiped out a greater proportion of humankind in a single epidemic than the Black Death.

Brought to Europe from China, it scythed through the continent from 1347 to 1351, killing about 30 million people -- about one in three of Europe's and nearly one in 12 of the world's population at the time.

Remarkably, more recent variants of the bacterium hardly vary compared to the original microbe, says the paper.

"Based on the reconstructed genome, we can say that the mediaeval plague is close to the root of all modern human pathogenic plague strains," said Krause.

"The ancient plague strain does not carry a single position that cannot be found in the same state in modern strains."

This deep similarity between ancient and modern plague calls into question the long-held assumption that virulence-enhancing mutations are what made Y. pestis so deadly to the Middle Ages.

Like Native American Indians who were exposed to smallpox, Europeans had never been exposed to the bacterium, said Krause.

"Plague was among the strongest sources of selection on the human population in the last few thousand years," he added. "People who were less susceptible due to mutations might have survived, and these (beneficial) mutations may have spread."

Another likely factor that worsened the Black Death's toll was social conditions, which were far worse compared to the 18th or 19th centuries. Poverty and malnutrition were rampant, and even the concept of hygiene was non-existent.

The onset of the so-called "Little Ice Age" could also have favoured the spread of the disease which, like many pathogens, travels more quickly in cold climes.

The same goes for the rats that carried the blood-sucking insects -- fleas or lice, perhaps both -- that transmit the disease.

Indeed, the species of rodent, Ratus ratus, that sowed terror across a continent in the 14th century is not the same as the one that transports plague today, Ratus norvegicus, Krause said.

The 1918-19 Spanish flu pandemic killed by some estimates 50 million people. In absolute terms, this was the deadliest pandemic in human history.

But with a world population that was close to two billion, the toll in relative terms was far smaller than that of the Black Death, when the number of humans was in the hundreds of millions.

Read more at Discovery News

New Diamonds Rock!

Diamonds may be a girl's best friend, but “new diamonds” may be an engineer's.

A new form of highly-compressed carbon may be even stronger than diamonds, since it may be able to withstand extreme pressure from all directions, unlike diamonds which are harder in one orientation than another.

Natural diamonds are created when carbon is subjected to extreme heat and pressure deep within the Earth. A team of Stanford University scientists created the “new diamonds” by compressing glassy carbon to above 400,000 times normal atmospheric pressure.

Carbon, the fourth most abundant element in the universe, can take on many forms, called allotropes. Diamonds and graphite are two familiar allotropes of carbon. Glassy carbon and buckminsterfullerenes are two others. Glassy carbon was first synthesized in the 1950's. It combines the properties of glass and ceramics with those of graphite.

The newly created allotrope, or “new diamond,” can withstand 1.3 million times normal atmospheric pressure in one direction while confined under a pressure of 600,000 times atmospheric levels in other directions. Diamonds are the only other substance which can withstand that kind of pressure.

Diamonds are crystals. The crystalline structure of diamonds means that the rock's hardness depends on its orientation.

Unlike diamonds, the new material is not a crystal. It is an amorphous material, meaning that its structure lacks the repeating atomic order of a diamond crystal. This quality could make the new material superior to diamonds, if it proves to be equally hard in all directions.

Read more at Discovery News

A new form of highly-compressed carbon may be even stronger than diamonds, since it may be able to withstand extreme pressure from all directions, unlike diamonds which are harder in one orientation than another.

Natural diamonds are created when carbon is subjected to extreme heat and pressure deep within the Earth. A team of Stanford University scientists created the “new diamonds” by compressing glassy carbon to above 400,000 times normal atmospheric pressure.

Carbon, the fourth most abundant element in the universe, can take on many forms, called allotropes. Diamonds and graphite are two familiar allotropes of carbon. Glassy carbon and buckminsterfullerenes are two others. Glassy carbon was first synthesized in the 1950's. It combines the properties of glass and ceramics with those of graphite.

The newly created allotrope, or “new diamond,” can withstand 1.3 million times normal atmospheric pressure in one direction while confined under a pressure of 600,000 times atmospheric levels in other directions. Diamonds are the only other substance which can withstand that kind of pressure.

Diamonds are crystals. The crystalline structure of diamonds means that the rock's hardness depends on its orientation.

Unlike diamonds, the new material is not a crystal. It is an amorphous material, meaning that its structure lacks the repeating atomic order of a diamond crystal. This quality could make the new material superior to diamonds, if it proves to be equally hard in all directions.

Read more at Discovery News

Oct 11, 2011

Early Celtic 'Stonehenge' Discovered in Germany's Black Forest

A huge early Celtic calendar construction has been discovered in the royal tomb of Magdalenenberg, nearby Villingen-Schwenningen in Germany's Black Forest. This discovery was made by researchers at the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum at Mainz in Germany when they evaluated old excavation plans. The order of the burials around the central royal tomb fits exactly with the sky constellations of the Northern hemisphere.

Whereas Stonehenge was orientated towards the sun, the more then 100 meter width burial mound of Magdalenenberg was focused towards the moon. The builders positioned long rows of wooden posts in the burial mound to be able to focus on the Lunar Standstills. These Lunar Standstills happen every 18,6 year and were the 'corner stones' of the Celtic calendar.

The position of the burials at Magdeleneberg represents a constellation pattern which can be seen between Midwinter and Midsummer. With the help of special computer programs, Dr. Allard Mees, researcher at the Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseum, could reconstruct the position of the sky constellations in the early Celtic period and following from that those which were visible at Midsummer. This archaeo-astronomic research resulted in a date of Midsummer 618 BC, which makes it the earliest and most complete example of a Celtic calendar focused on the moon.

Read more at Science Daily

Whereas Stonehenge was orientated towards the sun, the more then 100 meter width burial mound of Magdalenenberg was focused towards the moon. The builders positioned long rows of wooden posts in the burial mound to be able to focus on the Lunar Standstills. These Lunar Standstills happen every 18,6 year and were the 'corner stones' of the Celtic calendar.

The position of the burials at Magdeleneberg represents a constellation pattern which can be seen between Midwinter and Midsummer. With the help of special computer programs, Dr. Allard Mees, researcher at the Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseum, could reconstruct the position of the sky constellations in the early Celtic period and following from that those which were visible at Midsummer. This archaeo-astronomic research resulted in a date of Midsummer 618 BC, which makes it the earliest and most complete example of a Celtic calendar focused on the moon.

Read more at Science Daily

Megavirus May Be Stripped-Down Version of Normal Cell

About five years ago, biologists were surprised by the first discovery of an extremely large virus. Viruses are generally stripped down, efficient predators, only carrying as much DNA or RNA necessary to hijack their host and make extra copies of themselves. The newly discovered virus, called Mimivirus, was anything but stripped down; it carried a genome nearly the size of some bacterial species. And, instead of simply hijacking its host, the viral genome carried a lot of genes that replaced basic cellular functions, including some involved in DNA repair and the manufacturing of proteins.

The unusual size and gene content of the virus led one scientist to suggest that viruses could explain the origin of DNA-based life. If viruses carried all these genes, then it’s possible to imagine that one could set up shop in a cell and simply never leave, gradually taking over the remaining functions once performed by its host’s genetic material. This would explain the origin of DNA, which would distinguish the virus from its host’s genetic material, a holdover from the RNA world. It could also explain the existence of a distinct nucleus within Eukaryotic cells.

A paper is being released today, however, that argues that this scenario has things exactly backwards. Giant viruses, its authors argue, have all these genes normally associated with cells because, in their distant evolutionary past, they were once cells.

Mimivirus was discovered in an amoeba, so the authors of the new paper used a simple technique to look for its relatives: take three different species of amoeba, expose them to a variety of environmental samples, and see if anything big starts growing in them. They hit pay dirt with a sample obtained from an ocean monitoring station just off the coast of Chile. Despite the oceanic source, the virus grew nicely in fresh water amoebae. The site also gave the virus its name: Megavirus chilensis.

The authors followed its lifestyle, showing that it behaved much like Mimivirus, forming similar structures within its host cell that could only be distinguished using electron microscopy. They also sequenced its entire genome, which turned out to be the largest virus genome yet completed: 1.26 million base pairs of DNA (Megabases). Based on this sequence, Megavirus is a distant cousin of Mimivirus. Of its 1,120 protein-coding genes, over 250 have no equivalent in Mimivirus. But, of the genes that are shared, the sequences average about 50 percent identity on the protein level. This means that Megavirus is similar enough that it can be compared to Mimivirus, but different enough that it’s possible to make some inferences about the viruses’ evolutionary history.

And what they find supports the view that the virus started out with a much larger complement of genes. For example, Mimivirus has a suite of genes that can help repair DNA. Megavirus has those plus one other that is specialized for the repair of DNA damaged by UV light. The additional gene appears to be functional: Megavirus was able to grow following an exposure to UV that was sufficient to disable Mimivirus.

Both viruses share an identical set of genes involved in transcribing their DNA into RNA, and use an identical set of signals to indicate where the transcripts should start and stop. Mimivirus also contains a number of genes used in the translation of RNA into protein. Megavirus has those plus a few more, including additional genes that attach amino acids (components of proteins) onto RNAs for use in translation.

Clearly, the common genes suggest that the viruses share a common ancestor. This leaves two possibilities for the novel ones: either the ancestral virus had a larger collection and its descendants have lost different ones, or each virus picked up different genes from its hosts through a process called horizontal gene transfer. The authors favor the former explanation, because most of the genes specific to one of the two viruses don’t look like any gene present in their hosts (or any other gene we’ve ever seen, for that matter). This implies that horizontal gene transfer doesn’t seem to have done much to shape the viruses’ genomes.

So, when did the common ancestor exist? The authors line up a few of the conserved megavirus genes (including those of a more distantly related giant virus, CroV) with the equivalents in other eukaryotic species, and find that they branch off right at the base of the the eukaryotic lineage. In other words, the viruses seem to have had a common ancestor with eukaryotes, but it split off right after the eukaryotes diverged from bacteria and archaea. (This also argues against the horizontal gene transfer idea, since there doesn’t seem to be a species out there that the genes could have been transferred from.)

Read more at Wired

The unusual size and gene content of the virus led one scientist to suggest that viruses could explain the origin of DNA-based life. If viruses carried all these genes, then it’s possible to imagine that one could set up shop in a cell and simply never leave, gradually taking over the remaining functions once performed by its host’s genetic material. This would explain the origin of DNA, which would distinguish the virus from its host’s genetic material, a holdover from the RNA world. It could also explain the existence of a distinct nucleus within Eukaryotic cells.

A paper is being released today, however, that argues that this scenario has things exactly backwards. Giant viruses, its authors argue, have all these genes normally associated with cells because, in their distant evolutionary past, they were once cells.

Mimivirus was discovered in an amoeba, so the authors of the new paper used a simple technique to look for its relatives: take three different species of amoeba, expose them to a variety of environmental samples, and see if anything big starts growing in them. They hit pay dirt with a sample obtained from an ocean monitoring station just off the coast of Chile. Despite the oceanic source, the virus grew nicely in fresh water amoebae. The site also gave the virus its name: Megavirus chilensis.