Hopes for treating life-threatening diseases with cells taken from patients' own bodies have suffered a setback after research showed they might trigger severe immune reactions.

The surprise finding will be a hurdle for scientists working on induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, a variety of cell that holds promise for treating conditions as diverse as muscular dystrophy, Parkinson's and heart disease.

Like embryonic stem cells, iPS cells can develop into a range of body tissues, raising the possibility they could be used to grow healthy replacements for organs damaged by accidents or ravaged by disease.

Their creation in 2006 marked a turning point in stem cell research, because iPS cells suffer from none of the ethical issues that plague embryonic stem cells. Instead of being collected from surplus IVF embryos, iPS cells can be made from a patient's own skin cells, by rewinding their biological clocks to a more youthful state using a cocktail of chemicals.

Since iPS cells are genetically identical to their donors' cells, transplants of the cells were not expected to trigger the body's immune defences, but that view is now being questioned.

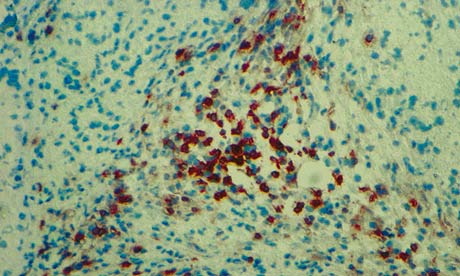

Writing in the journal Nature, a team led by Yang Xu at the University of California, San Diego, show that iPS cells triggered immune reactions when they were implanted into mice. In some cases, the cells were completely destroyed by the animals' immune systems.

Although the studies were done in rodents, the findings raise doubts over the use of iPS cells in future human therapies. "The assumption that cells derived from iPS cells are totally immune-tolerant has to be reevaluated before considering human trials," Xu said.

In the study, Xu's team took embryonic stem cells and iPS cells created from mouse tissue using different techniques, and transplanted them into genetically identical mice. The embryonic stem cells did not trigger an immune attack, but the iPS cells did. The most aggressive reactions were against iPS cells created using a virus.

Further tests revealed that the reprogramming process altered the expression of genes in the iPS cells, in some instances triggering the body's immune defences.

In many cases, only some cells appeared to cause an immune reaction, but Dr Xu said it was unclear which cells were the problematic ones. The answer could prove crucial to the future role of iPS cells in medicine.

"If it's only limited to certain cell types, then the others can still be used for cell transplantation without worry of being rejected, but if it's a widespread problem it's another issue. At the moment it is hard to say how big the hurdle is," Xu said.

While it may be possible to screen iPS cells and discard those likely to be rejected by the body, researchers hope to overcome the problem by finding more precise ways to create iPS cells so they hide from the immune system.

Paul Fairchild, director of the Oxford Stem Cell Institute, said nobody would have anticipated the immune rejection problem, but added it was too soon to know the implications for medical therapies based on iPS cells.

Read more at The Guardian

May 14, 2011

May 13, 2011

Tiny Iron Spheres Are Oldest Fossilized Space Dust

Japanese researchers have discovered the first micrometeorites known to land on Earth. No larger than droplets of fog, the spherical, iron-rich particles arrived 240 million years ago, 50 million years before the previous record-holding space dust.

“These are the the oldest fossil micrometeorites I’ve ever heard of, and the preservation is fantastic. They look exactly like their modern equivalents,” said geologist Susan Taylor of the U.S. Army Corps of engineers, who wasn’t involved in the work, published in Geology May 4. “If we can figure out where these things came from, they can help inform us about the history of the solar system.”

Meteorites and micrometeorites come from comets and asteroids, many as old as the Solar System itself. Although larger space rocks are more popular, they’re exceedingly rare. The overwhelming majority of extraterrestrial material is dust, of which some 30,000 tons falls from space each year..

About 90 percent vaporizes while passing through the Earth’s atmosphere, producing the sparks seen during meteor showers. Of what makes it to the ground, a small fraction gets stuck in mud, clay and other sediment that becomes fossilized.

By finding and comparing rare collections that span the geologic record, researchers can make guesses about cosmic conditions that Earth experienced throughout its history. Trouble is, the farther back in time geologists go, the harder it is to find well-preserved micrometeorites.

“I gave up trying to find them years ago,” said Taylor. “These aren’t tough particles. They’re fragile. Just a little acid etches out their glass, causing them to disintegrate. It’s amazing we find ones this old at all.”

Geologist Tetsuji Onoue of Kagoshima University discovered the new specimens in ancient shale and chert rock from Ajiro Island, at the southern tip of Japan.

To get to the roughly 300 micrometeorites, Onoue’s team crushed and sieved the rock, cleaned it with ultrasonic waves, then ran a magnet over the material. Under an electron microscope, they found 10-micron-wide spheres that somehow survived descent through Earth’s atmosphere, chemical weathering and 240 million years of punishing fossilization.

The samples are not representative sample of ancient space dust — everything but the iron-containing spheres dissolved away — but Taylor said they still offer a unique lens into cosmic history.

Read more at Wired Science

“These are the the oldest fossil micrometeorites I’ve ever heard of, and the preservation is fantastic. They look exactly like their modern equivalents,” said geologist Susan Taylor of the U.S. Army Corps of engineers, who wasn’t involved in the work, published in Geology May 4. “If we can figure out where these things came from, they can help inform us about the history of the solar system.”

Meteorites and micrometeorites come from comets and asteroids, many as old as the Solar System itself. Although larger space rocks are more popular, they’re exceedingly rare. The overwhelming majority of extraterrestrial material is dust, of which some 30,000 tons falls from space each year..

About 90 percent vaporizes while passing through the Earth’s atmosphere, producing the sparks seen during meteor showers. Of what makes it to the ground, a small fraction gets stuck in mud, clay and other sediment that becomes fossilized.

By finding and comparing rare collections that span the geologic record, researchers can make guesses about cosmic conditions that Earth experienced throughout its history. Trouble is, the farther back in time geologists go, the harder it is to find well-preserved micrometeorites.

“I gave up trying to find them years ago,” said Taylor. “These aren’t tough particles. They’re fragile. Just a little acid etches out their glass, causing them to disintegrate. It’s amazing we find ones this old at all.”

Geologist Tetsuji Onoue of Kagoshima University discovered the new specimens in ancient shale and chert rock from Ajiro Island, at the southern tip of Japan.

To get to the roughly 300 micrometeorites, Onoue’s team crushed and sieved the rock, cleaned it with ultrasonic waves, then ran a magnet over the material. Under an electron microscope, they found 10-micron-wide spheres that somehow survived descent through Earth’s atmosphere, chemical weathering and 240 million years of punishing fossilization.

The samples are not representative sample of ancient space dust — everything but the iron-containing spheres dissolved away — but Taylor said they still offer a unique lens into cosmic history.

Read more at Wired Science

American tycoon's fortune to be divided up after 92 years

When Wellington Burt died in 1919 at the age of 87, in Saginaw, Michigan, he ordered that the majority of his fortune not be distributed until 21 years after the death of his last surviving grandchild.

The unusual arrangement has been attributed to family feuds and to the eccentricity of Mr Burt, who was once among America's 10 richest men, but no one has been able to say conclusively why he chose it.

Except for a "favourite son" who received $30,000 a year from the bequest, Mr Burt's own children received only $1,000 to $5,000 a year – sums in line with that he left his domestic staff.

The last of the surviving grandchildren, Marion Lansill, died in November 1989. This meant the 21-year term ended towards the end of last year, prompting a flurry of applications for cash from relatives.

A total of 12 heirs, aged between 19 and 94, are due to receive payouts of up to $16 million later this month. Their totals will differ depending on their proximity to Mr Burt on the family tree.

Christina Cameron, his 19-year-old great-great-great granddaughter, is in line to receive up to $2.9 million. "I'm pretty sure he didn't like his family back then," said Miss Cameron, of Kentucky.

The legacy comes too late, however, for six of Mr Burt's children, seven grandchildren, six great-grandchildren and 11 great-great grandchildren, who did not live long enough or were ineligible.

Read more at The Telegraph

The unusual arrangement has been attributed to family feuds and to the eccentricity of Mr Burt, who was once among America's 10 richest men, but no one has been able to say conclusively why he chose it.

Except for a "favourite son" who received $30,000 a year from the bequest, Mr Burt's own children received only $1,000 to $5,000 a year – sums in line with that he left his domestic staff.

The last of the surviving grandchildren, Marion Lansill, died in November 1989. This meant the 21-year term ended towards the end of last year, prompting a flurry of applications for cash from relatives.

A total of 12 heirs, aged between 19 and 94, are due to receive payouts of up to $16 million later this month. Their totals will differ depending on their proximity to Mr Burt on the family tree.

Christina Cameron, his 19-year-old great-great-great granddaughter, is in line to receive up to $2.9 million. "I'm pretty sure he didn't like his family back then," said Miss Cameron, of Kentucky.

The legacy comes too late, however, for six of Mr Burt's children, seven grandchildren, six great-grandchildren and 11 great-great grandchildren, who did not live long enough or were ineligible.

Read more at The Telegraph

Solid Hydrogen Ice May Explain Interstellar Glow, Say Chemists

Astronomers have never been able to explain the weak glow they can see in interstellar space. Now new evidence suggests that solid hydrogen ice may be responsible.

Astronomers have long known that much of the universe is filled with diffuse hydrogen. In fact, they can see ionised hydrogen gas by the electromagnetic waves it gives off.

But back in the 1960s, some astronomers suggested that the interstellar medium might also be filled with solid hydrogen ice too. Various others later pointed out that this was unlikely because the ice ought to sublimate, even in the extreme cold of interstellar space.

More recently, astronomers have taken a second look at this idea and the pendulum of scientific opinion has begun to swing back in favour of hydrogen ice. That’s because chemists have discovered that hydrogen ice is more stable if it contains impurities. The extra ions in the lattice help to stabilise H2 ice.

So if hydrogen ice forms in space in the presence of other impurities, interstellar space could be full of it.

That raises an interesting question. Hydrogen ice is more or less transparent at optical frequencies. So how can we detect it in space?

Today, Ching Yeh Lin at the Australian National University in Canberra and a few buddies make an interesting suggestion. They say that when photons bombard hydrogen ice, they ought to ionise it creating ionised clusters of hydrogen and in particular H6+. This ion cluster does not form in hydrogen gas so its presence is a good marker for hydrogen ice.

The problem is that nobody knows what H6+ looks like–this work hasn’t yet been done in the lab. So Ching Yeh Lin and co have calculated from first principles its vibrational transitions. Their conclusion is that H6+ (and its deuterated cousin (HD)3+) ought to produce various emissions in the infrared part of the spectrum.

They then go on to compare their predictions with the emissions that astronomers can see coming from interstellar space.

TechReview

Astronomers have long known that much of the universe is filled with diffuse hydrogen. In fact, they can see ionised hydrogen gas by the electromagnetic waves it gives off.

But back in the 1960s, some astronomers suggested that the interstellar medium might also be filled with solid hydrogen ice too. Various others later pointed out that this was unlikely because the ice ought to sublimate, even in the extreme cold of interstellar space.

More recently, astronomers have taken a second look at this idea and the pendulum of scientific opinion has begun to swing back in favour of hydrogen ice. That’s because chemists have discovered that hydrogen ice is more stable if it contains impurities. The extra ions in the lattice help to stabilise H2 ice.

So if hydrogen ice forms in space in the presence of other impurities, interstellar space could be full of it.

That raises an interesting question. Hydrogen ice is more or less transparent at optical frequencies. So how can we detect it in space?

Today, Ching Yeh Lin at the Australian National University in Canberra and a few buddies make an interesting suggestion. They say that when photons bombard hydrogen ice, they ought to ionise it creating ionised clusters of hydrogen and in particular H6+. This ion cluster does not form in hydrogen gas so its presence is a good marker for hydrogen ice.

The problem is that nobody knows what H6+ looks like–this work hasn’t yet been done in the lab. So Ching Yeh Lin and co have calculated from first principles its vibrational transitions. Their conclusion is that H6+ (and its deuterated cousin (HD)3+) ought to produce various emissions in the infrared part of the spectrum.

They then go on to compare their predictions with the emissions that astronomers can see coming from interstellar space.

TechReview

Scientists have discovered an entirely new branch of life

NPR.ORG: If you think biologists have a pretty good idea about what lives on the Earth, think again. Scientists say they have just now discovered an entirely new branch on the tree of life. It’s made up of mysterious microscopic organisms. They’re related to fungus, but they are so different, you could argue that they deserve their very own kingdom, alongside plants and animals.

This comes as a big surprise. Just a few years ago, professor Timothy James and his colleagues sat down and wrote the definitive scientific paper to describe the fungal tree of life.

“We thought we knew what about the major groups that existed,” says James, who is curator of fungus at the University of Michigan. “Many groups have excellent drawings of these fungi from the last 150 years.”

Many fungi are already familiar. There are mushrooms, yeasts, molds like the one that makes penicillin, plant diseases such as rusts and smuts. Mildew in your shower is one, along with athlete’s foot. There are even fungi that infect insects — as well as fungi that live on other fungi.

Biologists figure they’ve probably only cataloged about 10 percent of all fungal species. But they thought they at least knew all of the major groups.

Thomas Richards, at the Natural History Museum in London, says biologists can mostly only study microscopic fungi if they can grow them in the lab.

“But the reality is most of the diversity of life we can’t grow in a laboratory. It exists in the environment,” he says. ”We know they have at least three stages to their life cycle,” Richards says. “One is where they attach to a host, which are photosynthetic algae. Another stage … they form swimming tails so they can presumably find food. And [there's] another stage, which we call the cyst phase, where they go to sleep.”

Full Story over at NPR.org

This comes as a big surprise. Just a few years ago, professor Timothy James and his colleagues sat down and wrote the definitive scientific paper to describe the fungal tree of life.

“We thought we knew what about the major groups that existed,” says James, who is curator of fungus at the University of Michigan. “Many groups have excellent drawings of these fungi from the last 150 years.”

Many fungi are already familiar. There are mushrooms, yeasts, molds like the one that makes penicillin, plant diseases such as rusts and smuts. Mildew in your shower is one, along with athlete’s foot. There are even fungi that infect insects — as well as fungi that live on other fungi.

Biologists figure they’ve probably only cataloged about 10 percent of all fungal species. But they thought they at least knew all of the major groups.

Thomas Richards, at the Natural History Museum in London, says biologists can mostly only study microscopic fungi if they can grow them in the lab.

“But the reality is most of the diversity of life we can’t grow in a laboratory. It exists in the environment,” he says. ”We know they have at least three stages to their life cycle,” Richards says. “One is where they attach to a host, which are photosynthetic algae. Another stage … they form swimming tails so they can presumably find food. And [there's] another stage, which we call the cyst phase, where they go to sleep.”

Full Story over at NPR.org

May 12, 2011

Neanderthals' Last Stand Possibly Found

A Neanderthal-style toolkit found in the frigid far north of Russia's Ural Mountains dates to 33,000 years ago and may mark the last refuge of Neanderthals before they went extinct, according to a new Science study.

Another possibility is that anatomically modern humans crafted the hefty tools using what's known as Mousterian technology associated with Neanderthals, but anthropologists believe that's unlikely.

"We consider it overwhelmingly probable that the Mousterian technology we describe was performed by Neanderthals, and thus that they indeed survived longer, that is until 33,000 years ago, than most other scientists believe," co-author Jan Mangerud, a professor emeritus in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Bergen and the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, told Discovery News.

Most anthropologists believe modern humans began to replace Neanderthals starting around 75,000 to 50,000 years ago. Project leader Ludovic Slimak said the study suggests "that Neanderthals did not disappear due to climate shifts or cultural inferiority. It is clear that, showing such adaptability, the Mousterian cultures can no longer be considered as archaic."

Slimak, a University of Toulouse le Mirail anthropologist, Mangerud, and their colleagues made the determinations after analyzing hundreds of stone artifacts and remains of woolly rhinoceros, reindeer, musk ox, brown bear, wolf and polar fox unearthed at a site called Byzovaya in the western foothills of the Polar Urals. Dates were obtained for sand at the site as well as for some of the bones, many of which "have cut marks that indicate processing by humans," according to the researchers.

The tools attributed to the Neanderthal's Mousterian style (named after the site of Le Moustier in southern France, where they were first identified) were mostly flakes, which the scientists recreated by banging a hard hammer on select stones. It's therefore likely that the original creators of the tools used a similar manufacturing method. The preserved flakes could have been used to make two-sided scrapers, perhaps for hunting, removing meat from bones, or working with animal hides.

Modern human tool-crafting methods associated with the Upper Paleolithic (between 40,000 and 10,000 years ago), on the other hand, "were generally focused on the production of what we call blade or bladelet technologies," Slimak said. The Byzovaya hominins did not apparently make such "blades," which were often crafted from organic materials like bone and ivory. So Slimak’s team argues that Neanderthals likely made the Byzovaya tools.

Even though Neanderthals may have disappeared from other locations throughout Europe and Asia, Slimak argues they likely persisted in this remote area near the Arctic Circle. Since conditions in the region were harsh even then, Slimak believes only strong individuals existing in a well-ordered, savvy group could have survived there.

Read more at Discovery News

Another possibility is that anatomically modern humans crafted the hefty tools using what's known as Mousterian technology associated with Neanderthals, but anthropologists believe that's unlikely.

"We consider it overwhelmingly probable that the Mousterian technology we describe was performed by Neanderthals, and thus that they indeed survived longer, that is until 33,000 years ago, than most other scientists believe," co-author Jan Mangerud, a professor emeritus in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Bergen and the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, told Discovery News.

Most anthropologists believe modern humans began to replace Neanderthals starting around 75,000 to 50,000 years ago. Project leader Ludovic Slimak said the study suggests "that Neanderthals did not disappear due to climate shifts or cultural inferiority. It is clear that, showing such adaptability, the Mousterian cultures can no longer be considered as archaic."

Slimak, a University of Toulouse le Mirail anthropologist, Mangerud, and their colleagues made the determinations after analyzing hundreds of stone artifacts and remains of woolly rhinoceros, reindeer, musk ox, brown bear, wolf and polar fox unearthed at a site called Byzovaya in the western foothills of the Polar Urals. Dates were obtained for sand at the site as well as for some of the bones, many of which "have cut marks that indicate processing by humans," according to the researchers.

The tools attributed to the Neanderthal's Mousterian style (named after the site of Le Moustier in southern France, where they were first identified) were mostly flakes, which the scientists recreated by banging a hard hammer on select stones. It's therefore likely that the original creators of the tools used a similar manufacturing method. The preserved flakes could have been used to make two-sided scrapers, perhaps for hunting, removing meat from bones, or working with animal hides.

Modern human tool-crafting methods associated with the Upper Paleolithic (between 40,000 and 10,000 years ago), on the other hand, "were generally focused on the production of what we call blade or bladelet technologies," Slimak said. The Byzovaya hominins did not apparently make such "blades," which were often crafted from organic materials like bone and ivory. So Slimak’s team argues that Neanderthals likely made the Byzovaya tools.

Even though Neanderthals may have disappeared from other locations throughout Europe and Asia, Slimak argues they likely persisted in this remote area near the Arctic Circle. Since conditions in the region were harsh even then, Slimak believes only strong individuals existing in a well-ordered, savvy group could have survived there.

Read more at Discovery News

May 11, 2011

Liver repaired with stem cells taken from skin and blood

Researchers have found a way to cheaply produce millions of the cells that can be injected into the organ and help regenerate it.

The technique involves converting skin and blood cells back to their original stem cell state and then into liver cells.

These were then injected into a liver with cirrhosis.

More than a tenth of the stem cells – – the most basic form of cell that can convert into any other cell – grafted on to the liver and started working without any significant side-effects.

The advantage of using stem cells taken from skin or blood – known as induced-pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) – is that they are cheap and can be multiplied easily in the laboratory.

Because they are from the patient there is also less danger of the body having a reaction to it.

The only other source of stem cells at the moment is from embryos and this is fraught with ethical issues.

"Our findings provide a foundation for producing functional liver cells for patients who suffer liver diseases and are in need of transplantation," said Professor Yoon-Young Jang, at Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, in Maryland.

"iPSC-derived liver cells not only can be generated in large amounts, but also can be tailored to each patient, preventing immune-rejection problems associated with liver transplants from unmatched donors or embryonic stem cells."

Although the liver can regenerate in the body, end-stage liver failure caused by diseases like cirrhosis and cancers eventually destroy the liver's regenerative ability, Jang says.

Currently, the only option for those patients is to receive a liver organ or liver cell transplant, a supply problem given the severe shortage of donor liver tissue for transplantation

iPSCs are made from adult cells that have been genetically reprogrammed to revert to an embryonic stem cell-like state, with the ability to transform into different cell types.

Human iPSCs can be generated from various tissues, including skin, blood and liver cells. For the study, Prof Jang and colleagues generated human iPSCs from a variety of adult human cells, including liver cells, bone marrow stem cells and skin cells.

Next, they chemically induced the iPSCs to differentiate first into immature and then more mature liver cell types.

Using mice with human-like liver cirrhosis, the researchers then injected the animals with two million human iPSC-derived liver cells or with normal human liver cells.

They discovered that the iPSC-derived liver cells engrafted to the mouse liver with an efficiency of eight to 15 per cent, a rate similar to the engraftment rate for adult human liver cells at 11 per cent.

Researchers also found the engrafted iPSCs worked well behaving like normal liver cells.

Read more at The Telegraph

The technique involves converting skin and blood cells back to their original stem cell state and then into liver cells.

These were then injected into a liver with cirrhosis.

More than a tenth of the stem cells – – the most basic form of cell that can convert into any other cell – grafted on to the liver and started working without any significant side-effects.

The advantage of using stem cells taken from skin or blood – known as induced-pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) – is that they are cheap and can be multiplied easily in the laboratory.

Because they are from the patient there is also less danger of the body having a reaction to it.

The only other source of stem cells at the moment is from embryos and this is fraught with ethical issues.

"Our findings provide a foundation for producing functional liver cells for patients who suffer liver diseases and are in need of transplantation," said Professor Yoon-Young Jang, at Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, in Maryland.

"iPSC-derived liver cells not only can be generated in large amounts, but also can be tailored to each patient, preventing immune-rejection problems associated with liver transplants from unmatched donors or embryonic stem cells."

Although the liver can regenerate in the body, end-stage liver failure caused by diseases like cirrhosis and cancers eventually destroy the liver's regenerative ability, Jang says.

Currently, the only option for those patients is to receive a liver organ or liver cell transplant, a supply problem given the severe shortage of donor liver tissue for transplantation

iPSCs are made from adult cells that have been genetically reprogrammed to revert to an embryonic stem cell-like state, with the ability to transform into different cell types.

Human iPSCs can be generated from various tissues, including skin, blood and liver cells. For the study, Prof Jang and colleagues generated human iPSCs from a variety of adult human cells, including liver cells, bone marrow stem cells and skin cells.

Next, they chemically induced the iPSCs to differentiate first into immature and then more mature liver cell types.

Using mice with human-like liver cirrhosis, the researchers then injected the animals with two million human iPSC-derived liver cells or with normal human liver cells.

They discovered that the iPSC-derived liver cells engrafted to the mouse liver with an efficiency of eight to 15 per cent, a rate similar to the engraftment rate for adult human liver cells at 11 per cent.

Researchers also found the engrafted iPSCs worked well behaving like normal liver cells.

Read more at The Telegraph

Cognitive Neuroscience book reveals why humans believe in gods

Dr Andy Thompson claims, in his new book, that the human mind generates religious beliefs as part of an evolutionary process. The recent revolution in cognitive science demonstrates the reasons why we create such myths, why we spread them and want other people to believe them too. His book shows the mechanisms in which the human mind constructs dogma, powers religious institutions and how irrational constructs can be harmful to society and it’s progression.

Every book bought contains a donation to the Richard Dawkins Foundation. The RDF finances research into the psychology of belief and religion, finances scientific education programs and materials, and publicises and supports secular charitable organisations.

It’s essential reading for all those who are interested in religious belief (whatever side of the fence you’re on), the way the mind works and gives an insight in to some of the recent breakthroughs in neuroscience and cognitive studies without being overly technical.

Click here to buy.

Play the game Phylo whilst performing important research

Though it may appear to be just a game, Phylo is actually a framework for harnessing the computing power of mankind to solve a common problem — Multiple Sequence Alignments.

Phylo is a game in which participants align sequences of DNA by shifting and moving puzzle pieces. Your score depends on how you arrange these pieces. You will be competing against a computer and other players in the community.

A sequence alignment is a way of arranging the sequences of DNA, RNA or protein to identify regions of similarity. These similarities may be consequences of functional, structural, or evolutionary relationships between the sequences. From such an alignment, biologists may infer shared evolutionary origins, identify functionally important sites, and illustrate mutation events. More importantly, biologists can trace the source of certain genetic diseases.

play the game here – Phylo

Phylo is a game in which participants align sequences of DNA by shifting and moving puzzle pieces. Your score depends on how you arrange these pieces. You will be competing against a computer and other players in the community.

A sequence alignment is a way of arranging the sequences of DNA, RNA or protein to identify regions of similarity. These similarities may be consequences of functional, structural, or evolutionary relationships between the sequences. From such an alignment, biologists may infer shared evolutionary origins, identify functionally important sites, and illustrate mutation events. More importantly, biologists can trace the source of certain genetic diseases.

play the game here – Phylo

May 10, 2011

Ghostly ‘Winged’ Octopus Caught on Camera

A rarely seen white deep-sea octopus has been captured on camera in high definition by researchers from the University of Washington. The octopus features two “wings” which make it look just like the ghosts from Mario videogames, aka Boos.

The Grimpoteuthis bathynectes octopus, also nicknamed the Dumbo octopus, was filmed with an HD video camera at a depth of more than 2,000 metres [6,500 feet] about 200 miles off the coast of Oregon.

Little is known about the deep-sea octopuses, which live near the hydrothermal vent fields — fissures in the Earth’s surface generally found near volcanically active places that release geothermally heated water.

Read more at Wired Science

May 9, 2011

Neanderthals Died Out Earlier Than Thought: Study

(Comparison of Neanderthal and modern human skeletons. Photo: K. Mowbray, Reconstruction: G. Sawyer and B. Maley, Copyright: Ian Tattersall)

Neanderthals may have died out 10,000 years earlier than is commonly believed, suggests new dating of the remains of a Neanderthal infant.

The finding, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, may revise the present Neanderthal timeline. It's commonly believed that Neanderthals from what is now Russia died out around 30,000 years ago. The latest discovery could push back the Neanderthal extinction, at least for this region, to 39,700 years ago, which was the age of the infant's fossil.

Since modern humans are believed to have arrived in the northern Caucasus region just a few hundred years beforehand, that means our species may not have had much, if any, time to interact with Neanderthals.

Lead author Ron Pinhasi of University College Cork said in a press release:

"It now seems much clearer that Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans did not co-exist in the Caucasus, and it is possible that this scenario is also true for most regions of Europe. Many of the previous dates for late Neanderthal occupation or sites across Europe are problematic.

...

This is simply an outcome of the fact that the association between the dated material and late Neanderthals is not always clear because we cannot always be certain whether archaeological stone tool assemblages, such as the Mousterian, that has been attributed in the case of Europe to Neanderthals, was not in some cases actually produced by modern humans. We have to directly date Neanderthal and anatomically modern human fossils to resolve this."

Pinhasi and his colleagues radiocarbon dated the Neanderthal infant remains, as well as the fossils for associated animal bones in Mezmaiskaya Cave, a key site in the northern Caucasus within European Russia. The revised dating indicates Neanderthals did not survive in this cave region much beyond the 39,700 years ago date, so maybe Mezmaiskaya Cave was a last stand for these large hominids.

Since their demise in this spot would appear to coincide with the arrival of our species, it's possible that we wiped them out if interaction occurred. Other studies strongly support that interbreeding took place at some sites, so I hope we made love and not war in Russia too.

Read more at Discovery News

Neanderthals may have died out 10,000 years earlier than is commonly believed, suggests new dating of the remains of a Neanderthal infant.

The finding, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, may revise the present Neanderthal timeline. It's commonly believed that Neanderthals from what is now Russia died out around 30,000 years ago. The latest discovery could push back the Neanderthal extinction, at least for this region, to 39,700 years ago, which was the age of the infant's fossil.

Since modern humans are believed to have arrived in the northern Caucasus region just a few hundred years beforehand, that means our species may not have had much, if any, time to interact with Neanderthals.

Lead author Ron Pinhasi of University College Cork said in a press release:

"It now seems much clearer that Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans did not co-exist in the Caucasus, and it is possible that this scenario is also true for most regions of Europe. Many of the previous dates for late Neanderthal occupation or sites across Europe are problematic.

...

This is simply an outcome of the fact that the association between the dated material and late Neanderthals is not always clear because we cannot always be certain whether archaeological stone tool assemblages, such as the Mousterian, that has been attributed in the case of Europe to Neanderthals, was not in some cases actually produced by modern humans. We have to directly date Neanderthal and anatomically modern human fossils to resolve this."

Pinhasi and his colleagues radiocarbon dated the Neanderthal infant remains, as well as the fossils for associated animal bones in Mezmaiskaya Cave, a key site in the northern Caucasus within European Russia. The revised dating indicates Neanderthals did not survive in this cave region much beyond the 39,700 years ago date, so maybe Mezmaiskaya Cave was a last stand for these large hominids.

Since their demise in this spot would appear to coincide with the arrival of our species, it's possible that we wiped them out if interaction occurred. Other studies strongly support that interbreeding took place at some sites, so I hope we made love and not war in Russia too.

Read more at Discovery News

Crocodile God Temple Featured Croc Nursery

Egyptian authorities put another archaeological site on the country’s tourist map yesterday by opening a visitor center at Madinet Madi in the Fayoum region south of Cairo.

Founded during the reigns of Amenemhat III (about 1859-1813 B.C.) and Amenemhat IV (about 1814-1805 B.C.) of the 12th Dynasty, Madinet Madi contains the ruins of the only Middle Kingdom temple in Egypt.

Approached by a paved processional way lined by lions and sphinxes, the temple was dedicated to the cobra-headed goddess Renenutet, and the crocodile-headed god, Sobek of Scedet, patron god of the region.

Now almost forgotten by tourists, the site was swarming with pilgrims in ancient times.

Indeed, 10 Coptic churches dating from the 5th to 7th centuries and the remains of a Ptolemaic temple dedicated to the crocodile god were unearthed in the past decades by renowned Egyptologist Edda Bresciani of Pisa University, who has been excavating the area since 1978.

Discovered more than 10 years ago, the temple featured a unique barrel-vaulted structure which was used for the incubation of crocodile eggs. According to Bresciani, the structure was basically a nursery for sacred crocodiles. Her team found dozens of eggs in different stages of maturation in a hole covered with a layer of sand. In the adjacent room, the archaeologist found a perfectly preserved pool.

"As they came out from the eggs, the crocodiles were kept in the pool," Bresciani wrote in the excavation report.

According to Bresciani, the crocodiles were bred only to be killed. As they were embalmed, they were sold to pilgrims to the Sobek temple.

Further evidence for the sacred crocodile business came from a nearby building, which contained another pool and other 60 crocodile eggs.

Almost forgotten in modern times, with its monuments appearing and disappearing with the windblown desert sand, Medinet Madi is now at the center of a development project which aims to preserve the site and make it a more tourist-friendly visitor destination.

Read more at Discovery News

Founded during the reigns of Amenemhat III (about 1859-1813 B.C.) and Amenemhat IV (about 1814-1805 B.C.) of the 12th Dynasty, Madinet Madi contains the ruins of the only Middle Kingdom temple in Egypt.

Approached by a paved processional way lined by lions and sphinxes, the temple was dedicated to the cobra-headed goddess Renenutet, and the crocodile-headed god, Sobek of Scedet, patron god of the region.

Now almost forgotten by tourists, the site was swarming with pilgrims in ancient times.

Indeed, 10 Coptic churches dating from the 5th to 7th centuries and the remains of a Ptolemaic temple dedicated to the crocodile god were unearthed in the past decades by renowned Egyptologist Edda Bresciani of Pisa University, who has been excavating the area since 1978.

Discovered more than 10 years ago, the temple featured a unique barrel-vaulted structure which was used for the incubation of crocodile eggs. According to Bresciani, the structure was basically a nursery for sacred crocodiles. Her team found dozens of eggs in different stages of maturation in a hole covered with a layer of sand. In the adjacent room, the archaeologist found a perfectly preserved pool.

"As they came out from the eggs, the crocodiles were kept in the pool," Bresciani wrote in the excavation report.

According to Bresciani, the crocodiles were bred only to be killed. As they were embalmed, they were sold to pilgrims to the Sobek temple.

Further evidence for the sacred crocodile business came from a nearby building, which contained another pool and other 60 crocodile eggs.

Almost forgotten in modern times, with its monuments appearing and disappearing with the windblown desert sand, Medinet Madi is now at the center of a development project which aims to preserve the site and make it a more tourist-friendly visitor destination.

Read more at Discovery News

Toddler Tyrannosaur Redefines 'Terrible Twos'

The youngest and most complete known skull and skeleton for a tyrannosaur reveal that even juveniles among these infamous carnivores were strong hunters, capable of outrunning and killing other dinosaurs, according to new research.

The remains, described in the latest Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, belong to a two to three-year-old Tarbosaurus bataar, the closest known relative of Tyrannosaurus rex. It lived 70 million years ago and died young of unknown causes.

While this juvenile dinosaur gives new meaning to the "terrible twos," it also provides evidence that young tyrannosaurs looked and behaved differently than their parents did.

"The adult's head would be much more robust and rugged-looking, with more prominent facial ornaments (such as various crests and bumps), whereas the juvenile's head would have been much sleeker and more delicate looking," co-author Lawrence Witmer told Discovery News. "Many of us humans get kind of nastier looking as we get older too!"

"There would have been other differences, such as longer, more gangly, legs in the juvenile and generally a more slender body," added Witmer, an Ohio University paleontologist.

He and his colleagues made the determinations after extensively analyzing the young dinosaur's remains, which were unearthed in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. The researchers believe the Tarbosaurus was nine feet in total length, about three feet high at the hip, and weighed about 70 pounds.

In contrast, adults of this species were 35 to 40 feet long, 15 feet high, and six tons in weight. The life expectancy was probably about 25 years, based on comparisons with T. rex.

"Tarbosaurus is found in the same rocks as giant herbivorous dinosaurs like the long-necked Opisthocoelicaudia and the duckbill hadrosaur Saurolophus," said Mahito Watabe, who led the expedition to Mongolia and is at the Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences in Okayama. "But the young juvenile Tarbosaurus would have hunted smaller prey, perhaps something like the bony-headed dinosaur Prenocephale."

The head of the youngster was too lightweight to handle the biting, twisting, and chomping required of its parents' larger prey, but the juvenile dinosaur's long legs suggest that it was a fast and agile runner. Prenocephale was probably just one of many animals that young Tarbosaurus likely hunted.

"There are also several lizards known from the Nemegt Formation, and they were other potential targets for the juvenile," co-author Takanobu Tsuihiji of Tokyo's National Museum of Nature and Science told Discovery News.

The differences between juvenile and adult tyrannosaurs may have reduced competition among them and strengthened their role as dominant predators in their environments. Since young Tarbosaurus was no weak toddler, the discovery helps to bolster the argument that tyrannosaurs were active predators and not just scavengers, as some other paleontologists have suggested.

That doesn't mean the meat-hungry dinosaurs would have passed up a free meal.

Read more at Discovery News

The remains, described in the latest Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, belong to a two to three-year-old Tarbosaurus bataar, the closest known relative of Tyrannosaurus rex. It lived 70 million years ago and died young of unknown causes.

While this juvenile dinosaur gives new meaning to the "terrible twos," it also provides evidence that young tyrannosaurs looked and behaved differently than their parents did.

"The adult's head would be much more robust and rugged-looking, with more prominent facial ornaments (such as various crests and bumps), whereas the juvenile's head would have been much sleeker and more delicate looking," co-author Lawrence Witmer told Discovery News. "Many of us humans get kind of nastier looking as we get older too!"

"There would have been other differences, such as longer, more gangly, legs in the juvenile and generally a more slender body," added Witmer, an Ohio University paleontologist.

He and his colleagues made the determinations after extensively analyzing the young dinosaur's remains, which were unearthed in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. The researchers believe the Tarbosaurus was nine feet in total length, about three feet high at the hip, and weighed about 70 pounds.

In contrast, adults of this species were 35 to 40 feet long, 15 feet high, and six tons in weight. The life expectancy was probably about 25 years, based on comparisons with T. rex.

"Tarbosaurus is found in the same rocks as giant herbivorous dinosaurs like the long-necked Opisthocoelicaudia and the duckbill hadrosaur Saurolophus," said Mahito Watabe, who led the expedition to Mongolia and is at the Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences in Okayama. "But the young juvenile Tarbosaurus would have hunted smaller prey, perhaps something like the bony-headed dinosaur Prenocephale."

The head of the youngster was too lightweight to handle the biting, twisting, and chomping required of its parents' larger prey, but the juvenile dinosaur's long legs suggest that it was a fast and agile runner. Prenocephale was probably just one of many animals that young Tarbosaurus likely hunted.

"There are also several lizards known from the Nemegt Formation, and they were other potential targets for the juvenile," co-author Takanobu Tsuihiji of Tokyo's National Museum of Nature and Science told Discovery News.

The differences between juvenile and adult tyrannosaurs may have reduced competition among them and strengthened their role as dominant predators in their environments. Since young Tarbosaurus was no weak toddler, the discovery helps to bolster the argument that tyrannosaurs were active predators and not just scavengers, as some other paleontologists have suggested.

That doesn't mean the meat-hungry dinosaurs would have passed up a free meal.

Read more at Discovery News

May 8, 2011

Learning how the brain does its coding

Most organisms with brains can store and process a staggering range of information. The fundamental unit of the brain, a single neuron, however, can only communicate in the simplest of manners, by sending a simple electrical pulse. The challenge of understanding how information is contained in the pattern of these pulses has been bothering neurobiologists for decades, and has been given its own name: neural coding.

In principle, there are two ways coding could be handled. In dense coding, a single neuron would convey lots of information through a complex series of voltage spikes. To a degree, however, this creates as many problems as it solves, since the neuron on the receiving end will have to be able to interpret this complex series properly, and separate it from operating noise.

The alternative, sparse coding, tends to be used for memory recall and sensory representations. Here, a single neuron only conveys a limited amount of information (i.e., there’s something moving horizontally in the field of vision) through a simple pulse of activity. Detailed information is then constructed by aggregating the inputs of lots of these neurons.

Full story at Arstechnica

In principle, there are two ways coding could be handled. In dense coding, a single neuron would convey lots of information through a complex series of voltage spikes. To a degree, however, this creates as many problems as it solves, since the neuron on the receiving end will have to be able to interpret this complex series properly, and separate it from operating noise.

The alternative, sparse coding, tends to be used for memory recall and sensory representations. Here, a single neuron only conveys a limited amount of information (i.e., there’s something moving horizontally in the field of vision) through a simple pulse of activity. Detailed information is then constructed by aggregating the inputs of lots of these neurons.

Full story at Arstechnica

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)