|

| DNA illustration |

A gene that regulates bone growth and muscle metabolism in mammals may take on an additional role as a promoter of brain maturation, cognition and learning in human and nonhuman primates, according to a new study led by neurobiologists at Harvard Medical School.

Describing their findings in the Nov. 10 issue of Nature, researchers say their work provides a dramatic illustration of evolutionary economizing and creative gene retooling -- mechanisms that contribute to the vast variability across species that share nearly identical set of genes yet differ profoundly in their physiology.

The research reveals that osteocrin -- a gene found in the skeletal muscles of all mammals and well-known for its role in bone growth and muscle function -- is completely turned off in rodent brains yet highly active in the brains of nonhuman primates and humans.

Notably, osteocrin was found predominantly in cells of the neocortex -- the most evolved part of the primate brain, which regulates sensory perception, spatial reasoning and higher-level thinking and language in humans.

The gene's marked presence in an area of the brain responsible for higher-level function and thought, the researchers said, suggests a possible role in the development of cognition, a cardinal feature that distinguishes the brains of human and nonhuman primates from those of other mammals.

Brain development in humans and other primates is profoundly affected by sensory experience and social interactions. Scientists have long sought to unravel genes in the brain that are turned on and off by experiences to fuel the rise of brain functions unique to such complex species.

The HMS team's findings -- part of an ongoing quest to elucidate the mechanisms that underlie human brain development, function and disease -- reveal that osteocrin is precisely one such gene, activated by sensory stimulation. Furthermore, the team added, this is the first illustration of evolutionary gene repurposing in the brain.

"We have uncovered what we believe is a critical clue into the evolution of the human brain, one that gives us a glimpse into the genetic mechanisms that may account for differences in cognition between mice and humans," said senior investigator Michael Greenberg, the Nathan Marsh Pusey Professor of Neurobiology and chair of the HMS Department of Neurobiology.

For their experiments, the team analyzed RNA levels -- the molecular footprints of gene activity -- in the brain cells of mice, rats and humans. Although many of the same genes were activated in both mouse and human brain cells, the scientists observed, a small subset of genes was activated solely in human brain cells. Much to the scientists' surprise, the bone gene osteocrin was most highly expressed in the human brain, yet completely shut off in the brain cells of mice.

Going a step further, the scientists placed brain cells from all three species in lab dishes and chemically re-created conditions that mimic sensory stimulation. Chemical stimulation activated osteocrin selectively in excitatory neurons, so called for their role in stimulating rather than dampening nerve signaling. But researchers noted something even more intriguing: The activity of the gene was most intense in neurons of the neocortex, the topmost layer of cells covering the brain and responsible for higher-level cognition, such as long-term memory, thought and language. At the same time, osteocrin was noticeably absent from other parts of the brain responsible for noncognitive functions such as spatial navigation, balance, breathing, heart rate and temperature control.

When researchers compared osteocrin levels to levels of another brain protein, BDNF, well known for its role in neuronal growth and repair, they noticed another striking difference. While BDNF was present throughout the brain, osteocrin was restricted to the neocortex and, to a lesser extent, the amygdala, an area of the brain thought to play a role in memory formation, decision making and emotional responses. Osteocrin was also markedly expressed in cells of the temporal lobe, which houses functions such as learning, memory and audio-visual processing -- and the occipital lobe, which houses the visual cortex, the area of the brain responsible for the processing of visual information.

Further analysis revealed that in the primate brain, sensory stimulation appears to switch on osteocrin through a previously unknown DNA enhancer. Enhancers -- snippets of DNA that act as the genome's regulators -- are the "handles" that turn on some genes while shutting off others. In doing so, enhancers can profoundly alter genetic expression, fueling dramatic differences between organisms with nearly identical DNA. The rodent versions of osteocrin lacked the stimulation-activated DNA enhancer, the analysis showed.

In yet another critical observation, researchers found the osteocrin enhancer was, in turn, switched on by a protein called MEF2. Mutations in MEF2 are a well-established cause of intellectual disability and neurodevelopmental disorders, so the link between the two begs further study, the researchers said, as it may portend a role for osteocrin in such developmental anomalies.

"Humans share many genes with rodents and as much as 90 percent of their DNA in some parts of the genome," says co-first author Gabriella Boulting, a neurobiologist at HMS. "In this case we see how turning up the expression of the same gene in a different location may precipitate dramatic differences in the function of brain cells."

Further analysis revealed that osteocrin's activation curbed the growth of neuronal dendrites -- branchlike projections responsible for transmitting signals from one brain cell to the next.

"Restricting dendritic growth is a precision-enhancing mechanism, essential to ensuring that neuronal wires don't get crossed and compromise signal transmission from one cell to the next," says study first co-author Bulent Ataman, a neurobiologist at HMS.

This observation, Ataman added, suggests that osteocrin's activity may help enhance nerve cell agility and proper signal transmission to ensure robust communication across neurons.

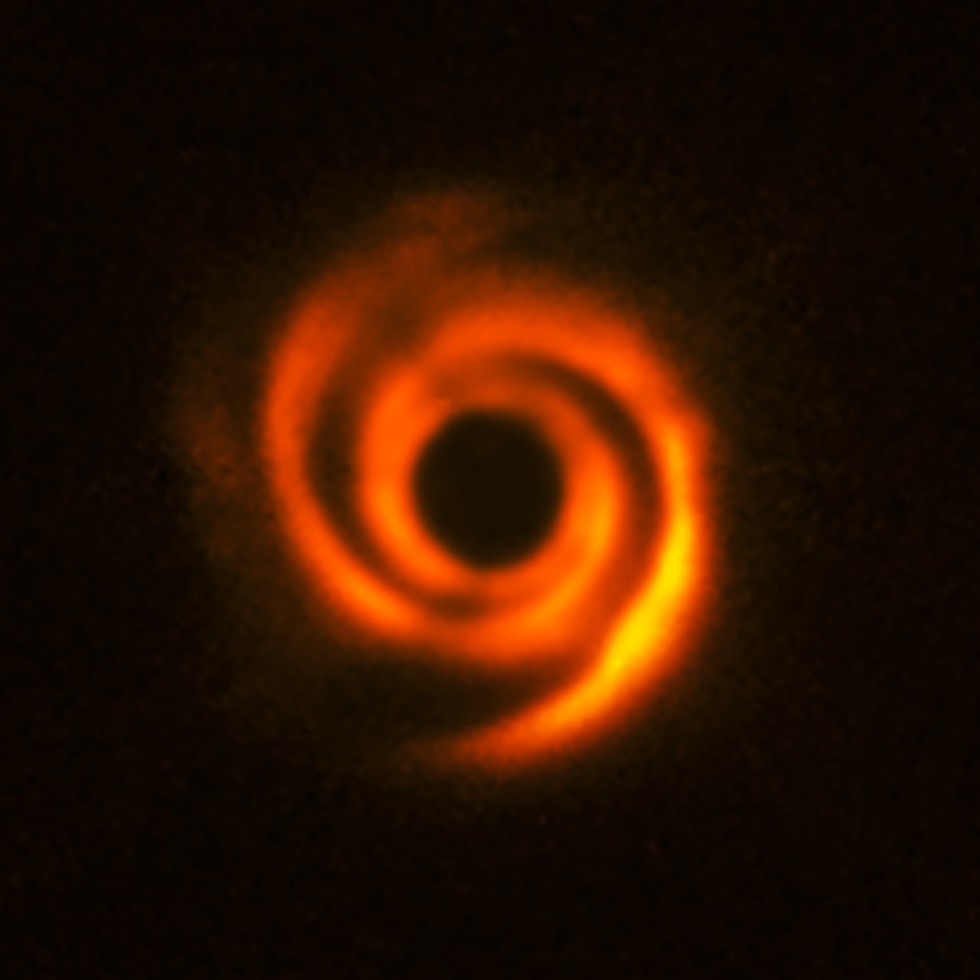

To confirm that the activity-induced gene expression observed in nerve cells in the lab also occurred in the functioning, intact brain, researchers temporarily blocked vision in one eye of a macaque, a common technique to study activity-triggered brain plasticity and visually-induced gene activation in the visual cortex. This proof-of-concept experiment, they surmised, would reveal whether osteocrin is, indeed, awakened by visual stimulation and shut off by its absence. A day later, the researchers observed that osteocrin expression was markedly higher in cells from the visually intact parts of the macaque brain, compared with cells in vision-deprived areas.

The findings illustrate a foundational principle in neurobiology -- abnormal visual experiences can interfere with the development and function of brain cells in the visual cortex, a phenomenon first described more than 50 years ago by David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel, two of the founding members of the Department of Neurobiology at HMS. The two shared the 1981 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries on visual information processing in the brain.

Read more at

Science Daily