Wouldn't it be great if, when landing a robotic mission on another planet, the lander or rover could just scoop a sample, drop it into a chemical analyzer and get a "positive" or "negative" result for extraterrestrial life?

Well, this chemistry test isn't so far fetched and scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., are working on a method that is 10,000 times more sensitive than any other method currently employed by spacecraft.

Focused on the detection of specific types of amino acid tied to life, the researchers propose mixing a liquid sample collected from the surface of an alien world with a chemical known as a liquid reagent. Then, by shining a laser across the mixture, the molecules it contains can be observed moving at different speeds when exposed to an electric field. From this, the different molecules can be identified and the whole thing can be done autonomously, no humans required.

The method known as "capillary electrophoresis" can be used to detect many different types of amino acids simultaneously.

"Our method improves on previous attempts by increasing the number of amino acids that can be detected in a single run," said researcher Jessica Creamer in a statement. "Additionally, it allows us to detect these amino acids at very low concentrations, even in highly salty samples, with a very simple 'mix and analyze' process."

The team has already tested the method on water taken from Mono Lake in California — a mass of salty water with an extreme alkalinity — and simultaneously analyzed 17 different amino acids.

"Using our method, we are able to tell the difference between amino acids that come from non-living sources like meteorites versus amino acids that come from living organisms," said Peter Willis, the project's principal investigator also at JPL.

Molecules like amino acids come in two different "chiralties" that are mirror images of one another. Non-organic sources contain roughly equal "left-" and "right-handed" chirality amino acids, whereas amino acids from living organisms are predominantly left-handed — for life on Earth in any case. This differentiation can be detected by capillary electrophoresis.

This method is exceedingly powerful for several reasons. Currently, NASA is putting great efforts into looking for habitable environments on Mars. We know that the Red Planet used to be a very wet place and there's evidence that suggests very briny sources of liquid water exists to this day. If life has ever taken hold on Mars, and if a future mission can directly sample this salty, toxic water, it's sensitive chemical analyses such as this that will likely track it down.

Read more at Discovery News

Jan 28, 2017

Transylvania Pterosaur Was the Top Predator on Its Prehistoric Island Home

A Transylvania pterosaur had a look all its own and was probably the top predator in its ancient island neighborhood, according to UK researchers who analyzed the neck anatomy of Hatzegopteryx, a giant flying reptile in the Azhdarchidae family.

Some of the biggest flying animals in the history of the planet were azhdarchid pterosaurs, such as Quetzalcoatlus, whose wingspan exceeded 30 feet (9 meters). Hatzegopteryx was certainly in that class, with a wingspan thought to have been up to 39 feet (12 meters).

In addition to the breadth of wing, azhdarchids are typically known for having had long necks and jaws. The behemoths foraged on the ground for small prey such a baby dinosaurs.

Hatzegopteryx, though, throws those characteristics for a bit of a loop, wrote Darren Naish, of the University of Southampton, and Mark Witton, of the University of Portsmouth, in the journal Peer J.

Thanks to a Late Cretaceous neck vertebra fossil from 66-70 million years ago found in Romania, it turns out that Hatzegopteryx was especially thick of neck, for a pterosaur, showing that some azhdarchids could appear proportionally much different than the conventional picture of the animals:

Read more at Discovery News

Some of the biggest flying animals in the history of the planet were azhdarchid pterosaurs, such as Quetzalcoatlus, whose wingspan exceeded 30 feet (9 meters). Hatzegopteryx was certainly in that class, with a wingspan thought to have been up to 39 feet (12 meters).

In addition to the breadth of wing, azhdarchids are typically known for having had long necks and jaws. The behemoths foraged on the ground for small prey such a baby dinosaurs.

Hatzegopteryx, though, throws those characteristics for a bit of a loop, wrote Darren Naish, of the University of Southampton, and Mark Witton, of the University of Portsmouth, in the journal Peer J.

Thanks to a Late Cretaceous neck vertebra fossil from 66-70 million years ago found in Romania, it turns out that Hatzegopteryx was especially thick of neck, for a pterosaur, showing that some azhdarchids could appear proportionally much different than the conventional picture of the animals:

Read more at Discovery News

Jan 26, 2017

Ancient Insect Found in Amber Is Literally One of a Kind

There's a new entry in the ancient bug-stuck-in-amber category: a 100-million-year-old, bulbous-eyed, alien-looking insect with an "E.T." head and a wide field of vision.

Found in Myanmar by George Poinar Jr., Oregon State University entomology professor emeritus, the bug – a wingless female – is such a bizarre, unique find that it has become a new insect order unto itself.

For the taxonomically inclined, that's a big deal. The roughly 1 million insect species known today are classified in just 31 orders (wasps, bees, and ants, for example live in the order Hymenoptera).

Now, though, make that 32 insect orders.

What wins the insect its new order are its unique features. It's a bug unlike any other, starting with its triangular head, which is reminiscent of the stereotypical space alien seen often in science fiction.

The way the "right triangle" head rests at the base of the creature's neck is unlike any insect ever known, according to Poinar.

"While insects with triangular-shaped heads are common today," Poinar and co-author Alex Brown wrote in a study just published in the journal Cretaceous Research, "the hypotenuse [the longest side] of the triangle is always located at the base of the head and attached to the neck, with the vertex at the apex of the head."

This bug turned that situation on its, well, head: The vertex was at the base of the neck. The head, then, along with its large lateral eyes, would have given the insect nearly 180-degree vision when it turned sideways, offering the ability to keep an eye out for things happening behind it, watching its own back, as it were.

As if that weren't enough, the insect secreted a chemical from its neck glands that, Poinar thinks, probably served to repel predators.

Poinar discovered the new bug in Myanmar's Hukawng Valley. Now it has a name, Aethiocarenus burmanicus, and the only seat in its new order Aethiocarenodea.

Long, thin legs propelled Aethiocarenus burmanicus' slender, flat body through its life among the dinosaurs. It likely lived in cracks within tree bark - an omnivore that dined on fare such as worms, mites and fungi. Despite features that probably helped it survive day to day, such as the see-behind-it vision, the amber-entombed insect went extinct, for reasons yet to be uncovered. Poinar and Brown think it may have disappeared due to the loss of its preferred habitat.

Read more at Discovery News

Found in Myanmar by George Poinar Jr., Oregon State University entomology professor emeritus, the bug – a wingless female – is such a bizarre, unique find that it has become a new insect order unto itself.

For the taxonomically inclined, that's a big deal. The roughly 1 million insect species known today are classified in just 31 orders (wasps, bees, and ants, for example live in the order Hymenoptera).

Now, though, make that 32 insect orders.

What wins the insect its new order are its unique features. It's a bug unlike any other, starting with its triangular head, which is reminiscent of the stereotypical space alien seen often in science fiction.

The way the "right triangle" head rests at the base of the creature's neck is unlike any insect ever known, according to Poinar.

"While insects with triangular-shaped heads are common today," Poinar and co-author Alex Brown wrote in a study just published in the journal Cretaceous Research, "the hypotenuse [the longest side] of the triangle is always located at the base of the head and attached to the neck, with the vertex at the apex of the head."

This bug turned that situation on its, well, head: The vertex was at the base of the neck. The head, then, along with its large lateral eyes, would have given the insect nearly 180-degree vision when it turned sideways, offering the ability to keep an eye out for things happening behind it, watching its own back, as it were.

As if that weren't enough, the insect secreted a chemical from its neck glands that, Poinar thinks, probably served to repel predators.

|

| "Take me to your leader?" New insect Aethiocarenus burmanicus looked like an alien. |

Long, thin legs propelled Aethiocarenus burmanicus' slender, flat body through its life among the dinosaurs. It likely lived in cracks within tree bark - an omnivore that dined on fare such as worms, mites and fungi. Despite features that probably helped it survive day to day, such as the see-behind-it vision, the amber-entombed insect went extinct, for reasons yet to be uncovered. Poinar and Brown think it may have disappeared due to the loss of its preferred habitat.

Read more at Discovery News

The Doomsday Clock Is Now Two-and-a-Half Minutes to Disaster

It's been 64 years since the world has been this close to doomsday.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has been updating the doomsday clock regularly for 70 years. On Thursday, they turned the hands to two-and-a-half minutes to midnight.

That's a bit closer than last year, when the clock was three minutes to midnight and the closest the clock has been to midnight since 1953 when it was two minutes to midnight. That move came following the U.S. detonating its first thermonuclear bomb and Russia detonating a hydrogen bomb. That's not exactly comforting company to be in.

In the early days, the threat of nuclear war was the primary gear turning the clock's arms. Climate change became a cog in 2007, moving the clock closer to midnight that year. Scientists invoked it in 2015 again, pushing the clock closer still to midnight. And in 2017, another cog was added: a rising tide of political leaders around the world making statements unhinged from facts.

"Facts are stubborn things and they must be taken into account if the future of humanity is preserved," said Lawrence Krauss, one of the clockmakers and a professor at Arizona State University.

When it comes to climate change, the facts are clear. The world had its hottest year ever recorded in 2016, the third year in a row that mark has been set. Arctic sea ice has been decimated by repeated heat waves, seas continue to rise and researchers have warned of instability driven by climate shocks.

The cause is human's pouring carbon pollution into the atmosphere.

Yet despite knowing all of that, scientists have stressed that world is not doing enough to put humanity on course to avoid catastrophic climate change. David Titley, a professor at Penn State and one of the authors of the new doomsday clock report, said that while the Paris Agreement represents a positive step, the climate talks in Morocco late last year didn't move the ball forward enough.

While these actions weighed on the decision to move the clock's hands closer to midnight, scientists also considered another disturbing trend of world leaders espousing policies and making statements not tied to evidence.

There's no more stark example than the rise of Donald Trump in the U.S. He has espoused climate science denialism as have many of his cabinet nominees and advisors. He's also made false statements on dozens of topics, from voter fraud to the size of his inauguration crowd. Taken individually, they indicate a penchant for embellishment. Taken together, they represent a willful disregard for reality, one that could have wide-ranging consequences on policy here and abroad.

This is hugely problematic when it comes to climate change, where the U.S. stands as an outlier with the only head of state to deny the science behind it. This is the exact moment when the world needs to be doing more to address climate change. Yet the current administration of the world's largest historical emitter is poised to ignore this fact, putting the future of humanity at risk.

"Nuclear weapons and climate change are precisely the sort of complex existential threats that cannot be properly managed without access to and reliance on expert knowledge," the scientists wrote in their report.

Read more at Discovery News

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has been updating the doomsday clock regularly for 70 years. On Thursday, they turned the hands to two-and-a-half minutes to midnight.

That's a bit closer than last year, when the clock was three minutes to midnight and the closest the clock has been to midnight since 1953 when it was two minutes to midnight. That move came following the U.S. detonating its first thermonuclear bomb and Russia detonating a hydrogen bomb. That's not exactly comforting company to be in.

In the early days, the threat of nuclear war was the primary gear turning the clock's arms. Climate change became a cog in 2007, moving the clock closer to midnight that year. Scientists invoked it in 2015 again, pushing the clock closer still to midnight. And in 2017, another cog was added: a rising tide of political leaders around the world making statements unhinged from facts.

"Facts are stubborn things and they must be taken into account if the future of humanity is preserved," said Lawrence Krauss, one of the clockmakers and a professor at Arizona State University.

When it comes to climate change, the facts are clear. The world had its hottest year ever recorded in 2016, the third year in a row that mark has been set. Arctic sea ice has been decimated by repeated heat waves, seas continue to rise and researchers have warned of instability driven by climate shocks.

The cause is human's pouring carbon pollution into the atmosphere.

Yet despite knowing all of that, scientists have stressed that world is not doing enough to put humanity on course to avoid catastrophic climate change. David Titley, a professor at Penn State and one of the authors of the new doomsday clock report, said that while the Paris Agreement represents a positive step, the climate talks in Morocco late last year didn't move the ball forward enough.

While these actions weighed on the decision to move the clock's hands closer to midnight, scientists also considered another disturbing trend of world leaders espousing policies and making statements not tied to evidence.

There's no more stark example than the rise of Donald Trump in the U.S. He has espoused climate science denialism as have many of his cabinet nominees and advisors. He's also made false statements on dozens of topics, from voter fraud to the size of his inauguration crowd. Taken individually, they indicate a penchant for embellishment. Taken together, they represent a willful disregard for reality, one that could have wide-ranging consequences on policy here and abroad.

This is hugely problematic when it comes to climate change, where the U.S. stands as an outlier with the only head of state to deny the science behind it. This is the exact moment when the world needs to be doing more to address climate change. Yet the current administration of the world's largest historical emitter is poised to ignore this fact, putting the future of humanity at risk.

"Nuclear weapons and climate change are precisely the sort of complex existential threats that cannot be properly managed without access to and reliance on expert knowledge," the scientists wrote in their report.

Read more at Discovery News

Human-Pig Embryos Have Arrived, Holding Promise for Organ Transplants

When research on chimeras, organisms containing cells from different species, started to take off a few decades ago, the premise was so unorthodox that the word "chimera" (pronounced ky-MEER-uh) — the name of a fire-breathing hybrid beast in Greek mythology — was often interpreted as "crazy idea."

Even nuttier was the notion that scientists could inject human cells into another animal to possibly create a human-ish organism.

Much has changed over the years, with human cells routinely transferred to mice for studies on cancer, immunity and more. Now, in an extraordinary step, scientists have created chimera embryos that are part-human, part-pig.

"Our ultimate goal of this research is to produce functional and transplantable human organs using large host animals to solve the world-wide shortage of organ donors," Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, senior author of a paper on the research, told Seeker. "This is a dream, really, and it may take years to achieve this goal. Our current study only marks the first step, although a very important one, toward that goal."

Chimeras' Mythical Past

Even Belmonte, who is a professor in the Salk Institute for Biological Studies' Gene Expression Laboratory, can see how some people might be shocked by the idea of a human-pig chimera.

"Interspecies chimeras have captured the wild imaginations of both ancient civilizations and modern society," he said. "They are often depicted as fearsome creatures in Greek mythology. But actually chimera-form figures have also been worshiped as deities in polytheistic religions."

It can be a stretch to pair thoughts of such organisms, given their mythological connotations, with the sobering realities concerning organ transplant needs. In the United States alone, approximately 22 people die each day waiting for such a transplant. Both here and around the world, there is a dire shortage of organs to meet medical needs. If a patient does receive a donor organ, his or her body might reject it, or the person's risk for cancer might increase.

The idea is to inject human stem cells into animal embryos and allow the stem cells to grow into the missing organ, which would then be harvested. Although researchers can turn stem cells into specific cell types, the results are not equivalent to cells produced within embryos. In short, they can't just grow viable human organs in a lab with only human cells — at least not with today's scientific capabilities.

"Currently there is no technology to culture embryos in the lab beyond a few days," Belmonte said. "Our understanding of animal development is still very limited and we simply don't have the information and technology to replicate this process in vitro. This is exactly why we turned to use animals, such as the pig, to help guide human cells to become functional organs and tissues."

From a Rat-Mouse to a Pig-Human

Belmonte collaborated with lead author Jun Wu and an international team of scientists for the breakthrough study, which is published in the journal Cell. The path to the pig-human chimera required several steps.

To test their methods, the researchers first created a rat-mouse chimera, a feat initially achieved back in 2010 by another scientific team. The chimera in this case, however, lived the entire lifespan of a mouse (two years), and aged normally.

"To our best knowledge, this is the longest-lived rat-mouse chimera to date," Belmonte said.

He and his colleagues next used gene-editing and stem-cell technologies to grow a rat heart, eyes and pancreas. Another research team this week reported in the journal Nature that they grew mouse pancreases in rats, and then used them to cure diabetes in mice.

As senior author Hiromitsu Nakauchi of Stanford University and his colleagues wrote, the "data provide proof-of-principle evidence for the therapeutic potential" of such work.

Belmonte and his team additionally grew a rat gallbladder within their mouse-rat chimera. Wu said that rats in nature do not have a gallbladder. Somehow they lost it over the 18 million years since mice and rats separated evolutionarily.

The team then faced the bigger challenge: introducing human cells into a non-rodent organism. Even if a human-mouse chimera could produce organs, these organs clearly would be too tiny for human medical needs. So Belmonte and his colleagues decided to use cow and pig embryos for the hosts. Experiments with cow embryos proved to be more difficult and costly than those on pigs, so they chose to focus solely on pigs.

"Most of the pigs used in this study were housed in farms used for meat production, rather than research purposes," Belmonte explained. "We had to convince the farmers to collaborate on this project. In addition, we cannot perform experiments whenever we want. For example, farms are typically closed during the summer due to hot weather."

The researchers persevered, injecting several different forms of human stem cells into pig embryos to see which would survive best. Those that did were "intermediate" human pluripotent stem cells. So-called "naïve" cells have unrestricted developmental potential, while "primed" cells have developed further.

"Intermediate cells are somewhere in between," Wu noted.

The human cells survived and formed the human-pig chimera embryos, which were allowed to develop for three to four weeks.

"Once the implants were removed," Belmonte said, "the [host] sows were euthanized and incinerated."

Cautions and Concerns

One reason the sows were incinerated was to eliminate any chance of the human cells escaping into an adult pig's body. Belmonte assured that the chances of that happening are "extremely unlikely," in any case.

"Ethically there have been some concerns raised about generating animal chimeras with human cells, particularly in cases where the cells might contribute extensively to the brain or to the germ cells," Janet Rossant, a senior scientist and chief of research emeritus at the Hospital for Sick Children, told Seeker. "This possibility needs to be carefully assessed in each specific experimental protocol and steps put in place to try to restrict unwanted contributions to tissues other than the ones required."

Read more at Discovery News

Even nuttier was the notion that scientists could inject human cells into another animal to possibly create a human-ish organism.

Much has changed over the years, with human cells routinely transferred to mice for studies on cancer, immunity and more. Now, in an extraordinary step, scientists have created chimera embryos that are part-human, part-pig.

"Our ultimate goal of this research is to produce functional and transplantable human organs using large host animals to solve the world-wide shortage of organ donors," Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, senior author of a paper on the research, told Seeker. "This is a dream, really, and it may take years to achieve this goal. Our current study only marks the first step, although a very important one, toward that goal."

Chimeras' Mythical Past

Even Belmonte, who is a professor in the Salk Institute for Biological Studies' Gene Expression Laboratory, can see how some people might be shocked by the idea of a human-pig chimera.

"Interspecies chimeras have captured the wild imaginations of both ancient civilizations and modern society," he said. "They are often depicted as fearsome creatures in Greek mythology. But actually chimera-form figures have also been worshiped as deities in polytheistic religions."

The idea is to inject human stem cells into animal embryos and allow the stem cells to grow into the missing organ, which would then be harvested. Although researchers can turn stem cells into specific cell types, the results are not equivalent to cells produced within embryos. In short, they can't just grow viable human organs in a lab with only human cells — at least not with today's scientific capabilities.

"Currently there is no technology to culture embryos in the lab beyond a few days," Belmonte said. "Our understanding of animal development is still very limited and we simply don't have the information and technology to replicate this process in vitro. This is exactly why we turned to use animals, such as the pig, to help guide human cells to become functional organs and tissues."

From a Rat-Mouse to a Pig-Human

Belmonte collaborated with lead author Jun Wu and an international team of scientists for the breakthrough study, which is published in the journal Cell. The path to the pig-human chimera required several steps.

To test their methods, the researchers first created a rat-mouse chimera, a feat initially achieved back in 2010 by another scientific team. The chimera in this case, however, lived the entire lifespan of a mouse (two years), and aged normally.

|

| Rat-mouse chimera as a 1-year-old. |

He and his colleagues next used gene-editing and stem-cell technologies to grow a rat heart, eyes and pancreas. Another research team this week reported in the journal Nature that they grew mouse pancreases in rats, and then used them to cure diabetes in mice.

As senior author Hiromitsu Nakauchi of Stanford University and his colleagues wrote, the "data provide proof-of-principle evidence for the therapeutic potential" of such work.

Belmonte and his team additionally grew a rat gallbladder within their mouse-rat chimera. Wu said that rats in nature do not have a gallbladder. Somehow they lost it over the 18 million years since mice and rats separated evolutionarily.

The team then faced the bigger challenge: introducing human cells into a non-rodent organism. Even if a human-mouse chimera could produce organs, these organs clearly would be too tiny for human medical needs. So Belmonte and his colleagues decided to use cow and pig embryos for the hosts. Experiments with cow embryos proved to be more difficult and costly than those on pigs, so they chose to focus solely on pigs.

"Most of the pigs used in this study were housed in farms used for meat production, rather than research purposes," Belmonte explained. "We had to convince the farmers to collaborate on this project. In addition, we cannot perform experiments whenever we want. For example, farms are typically closed during the summer due to hot weather."

The researchers persevered, injecting several different forms of human stem cells into pig embryos to see which would survive best. Those that did were "intermediate" human pluripotent stem cells. So-called "naïve" cells have unrestricted developmental potential, while "primed" cells have developed further.

"Intermediate cells are somewhere in between," Wu noted.

The human cells survived and formed the human-pig chimera embryos, which were allowed to develop for three to four weeks.

"Once the implants were removed," Belmonte said, "the [host] sows were euthanized and incinerated."

Cautions and Concerns

One reason the sows were incinerated was to eliminate any chance of the human cells escaping into an adult pig's body. Belmonte assured that the chances of that happening are "extremely unlikely," in any case.

"Ethically there have been some concerns raised about generating animal chimeras with human cells, particularly in cases where the cells might contribute extensively to the brain or to the germ cells," Janet Rossant, a senior scientist and chief of research emeritus at the Hospital for Sick Children, told Seeker. "This possibility needs to be carefully assessed in each specific experimental protocol and steps put in place to try to restrict unwanted contributions to tissues other than the ones required."

Read more at Discovery News

This Is Why Some People Don't Believe in Scientific Facts

US science agencies reported in early January that 2016 surpassed both 2014 and 2015 as the hottest year on record. Sixteen of the warmest 17 years ever measured have occurred since 2000. Yet, only 45 percent of Americans agree with the scientific consensus that the planet is warming and it's a very serious problem.

Acceptance of scientific fact divides along partisan lines in the US. Many Republicans doubt the existence of climate change, or that it's a problem caused by humans, despite the plethora of scientific evidence to support it.

Democrats are far more likely to consider climate change a serious problem.

Questioning the validity of science is nothing new in the United States. While researchers have long identified ideology and beliefs as driving forces behind scientific doubt, whether it's climate change, vaccinations or even the link between tobacco and cancer, the recent, high-profile skepticism of proven scientific theories is renewing the importance of science literacy.

Matthew Hornsey, a psychology professor from the University of Queensland, has looked extensively at why some people embrace — and others resist — scientific messages about climate change, vaccines and evolution, among other topics.

In his most recent study, Hornsey led a team that conducted a series of observational studies, surveys and experiments, aimed at revealing the ideologies, cultural norms and cognitive processes that lead some people to question the validity of science. Their goal is to make future science messaging more effective on skeptics.

It's tempting to think that skepticism is an affliction of the ill-informed, but Hornsey found this to be untrue.

"In fact, among Republicans, climate skepticism is higher among those who are more educated," Hornsey said. "Education in some ways gives you the skills and resources to cherry-pick data and to curate your own sense of reality, one that's in-line with your underlying worldviews," he added.

It's also easy to think, Hornsey said, that all skeptics must have similar geographic, economic or cultural backgrounds. But researchers failed to find a single commonality that was true for all skeptics across the different areas of science that receive the most criticism.

"If you've got a group of climate skeptics in the same room as a group of anti-vaxxers, for example, they'd probably have very little in common," Hornsey commented.

People who are skeptical of science treat facts as more or less relevant depending on whether it supports their opinion or ideology. Saying something is a "fact" or "data" does not change their mind.

Hornsey said skeptics often manipulate data to support their ideas. "1998 was an unusually hot year, so if you look at a graph of global temperatures that starts in 1998, it gives the impression that warming is slower than it would if you started the graph in any other year," he said.

Read more at Discovery News

Acceptance of scientific fact divides along partisan lines in the US. Many Republicans doubt the existence of climate change, or that it's a problem caused by humans, despite the plethora of scientific evidence to support it.

Democrats are far more likely to consider climate change a serious problem.

Questioning the validity of science is nothing new in the United States. While researchers have long identified ideology and beliefs as driving forces behind scientific doubt, whether it's climate change, vaccinations or even the link between tobacco and cancer, the recent, high-profile skepticism of proven scientific theories is renewing the importance of science literacy.

Matthew Hornsey, a psychology professor from the University of Queensland, has looked extensively at why some people embrace — and others resist — scientific messages about climate change, vaccines and evolution, among other topics.

In his most recent study, Hornsey led a team that conducted a series of observational studies, surveys and experiments, aimed at revealing the ideologies, cultural norms and cognitive processes that lead some people to question the validity of science. Their goal is to make future science messaging more effective on skeptics.

It's tempting to think that skepticism is an affliction of the ill-informed, but Hornsey found this to be untrue.

"In fact, among Republicans, climate skepticism is higher among those who are more educated," Hornsey said. "Education in some ways gives you the skills and resources to cherry-pick data and to curate your own sense of reality, one that's in-line with your underlying worldviews," he added.

It's also easy to think, Hornsey said, that all skeptics must have similar geographic, economic or cultural backgrounds. But researchers failed to find a single commonality that was true for all skeptics across the different areas of science that receive the most criticism.

"If you've got a group of climate skeptics in the same room as a group of anti-vaxxers, for example, they'd probably have very little in common," Hornsey commented.

People who are skeptical of science treat facts as more or less relevant depending on whether it supports their opinion or ideology. Saying something is a "fact" or "data" does not change their mind.

Hornsey said skeptics often manipulate data to support their ideas. "1998 was an unusually hot year, so if you look at a graph of global temperatures that starts in 1998, it gives the impression that warming is slower than it would if you started the graph in any other year," he said.

Read more at Discovery News

Jan 25, 2017

Parasitic 'Crypt-Keeper' Wasp Eats Through Its Host's Head

If there were a horror movie set in the animal kingdom, a turquoise-green insect named the "crypt-keeper wasp" would likely play a starring role. A new study has found that this crafty, parasitic wasp can manipulate other parasitic wasps to finish an assigned task and then become its meal.

The amber-colored victim is known as the "crypt gall wasp" (Bassettia pallida). It nests in tiny cavities called "crypts" on its host tree, which provides free nutrition throughout its development. When the adult wasp is ready to leave, it chews a hole through the tree's woody tissue and makes its way out. But for some gall wasps, things don't go according to plan. [The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

Instead of exiting the hole they make, the wasps would plug the holes with their head and die, researchers found. This is because the wasps are being manipulated by another crypt-residing wasp that capitalizes on the gall wasps' ability to chew a hole for its own exit. After the "crypt-keeper wasp" gets its host to create a hole, it eats its own way through the host. This grisly behavior earned the wasp its scientific name, Euderus set (Set being the ancient Egyptian god of evil).

To learn how the wasp benefits from manipulating its host into plugging the hole, scientists covered some head-plugged holes with bark. When the crypt-keeper wasp had to get through the extra bark, it was three times more likely to get trapped in the crypt and die than a wasp that had to get through only the head and no bark, said lead study author Kelly Weinersmith, a parasitologist at Rice University in Houston.

"So, it looks like the specific purpose of the manipulation is to help the crypt-keeper wasps emerge, because they are weaker excavators than their hosts," Weinersmith told Live Science. "They need the hosts to do that work for them, so they can get out."

Details of how a crypt-keeper female zeroes in on a developing gall wasp's crypt are yet to be uncovered. Weinersmith thinks a female either lays an egg directly into the body of the host or into the crypt next to the host using its egg-laying organ.

When the scientists cut open stems to reveal the inside of the head-plugged crypts, they found larvae and pupae of the keeper wasp lying partly inside the body of their hosts, with the host's entrails missing. "We don't know if they eat their way out or if they get to that development stage and then eat their way in," said Weinersmith. Either way, the host ends up dead.

Because all but four of the 168 head-plugged crypts studied had a keeper wasp, it's clear that the gall wasps did not die from accidentally getting stuck in the holes as they tried to emerge. Moreover, the escape holes that the parasitized hosts made were smaller than those of non-parasitized gall wasps, indicating manipulation by the crypt-keeper wasp, the researchers said.

Read more at Discovery News

The amber-colored victim is known as the "crypt gall wasp" (Bassettia pallida). It nests in tiny cavities called "crypts" on its host tree, which provides free nutrition throughout its development. When the adult wasp is ready to leave, it chews a hole through the tree's woody tissue and makes its way out. But for some gall wasps, things don't go according to plan. [The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

Instead of exiting the hole they make, the wasps would plug the holes with their head and die, researchers found. This is because the wasps are being manipulated by another crypt-residing wasp that capitalizes on the gall wasps' ability to chew a hole for its own exit. After the "crypt-keeper wasp" gets its host to create a hole, it eats its own way through the host. This grisly behavior earned the wasp its scientific name, Euderus set (Set being the ancient Egyptian god of evil).

To learn how the wasp benefits from manipulating its host into plugging the hole, scientists covered some head-plugged holes with bark. When the crypt-keeper wasp had to get through the extra bark, it was three times more likely to get trapped in the crypt and die than a wasp that had to get through only the head and no bark, said lead study author Kelly Weinersmith, a parasitologist at Rice University in Houston.

"So, it looks like the specific purpose of the manipulation is to help the crypt-keeper wasps emerge, because they are weaker excavators than their hosts," Weinersmith told Live Science. "They need the hosts to do that work for them, so they can get out."

Details of how a crypt-keeper female zeroes in on a developing gall wasp's crypt are yet to be uncovered. Weinersmith thinks a female either lays an egg directly into the body of the host or into the crypt next to the host using its egg-laying organ.

|

| In this photo, the bark has been dissected away to reveal two Bassettia pallida adults residing within their crypts. |

|

| The crypt gall wasp, Bassettia pallida. |

Read more at Discovery News

Why We Fall for Fake News and How to Bust It

Even though the election is over, fake news and daily disputes over what constitutes a fact haven't really gone away.

While meeting with congressional leaders Monday, President Trump repeated his claim that several million votes for Hillary Clinton were illegal, despite the lack of evidence and statements to the contrary by elections officials. Trump also claimed that his inauguration brought more than a million people to the National Mall in Washington, despite photographic evidence disproving the statement.

Measuring the impact of fake news spread through Facebook or Twitter is more difficult. Did made-up reports of pre-election ballot-stuffing for Hillary Clinton in Ohio before the election change any votes? Perhaps not, but it did lead the story's original author, a Republican legislative aide in Maryland, to lose his job last week

On many college campuses, professors are teaching their students identify and analyze fake news shared on social media, while some are even teaching students how to write their own fake news stories as a form of satire to make a bigger point about critical thinking.

"It's become such a big part of public discourse," said Sergio Figueiredo, assistant professor of English at Kennesaw State University in Georgia. "Whether its President Trump's press secretary talking about 'alternative facts' or CNN saying it's not going to put out statements from press briefings if not deemed accurate."

Figueiredo, who teaches rhetoric as well as social media writing, say, his students sometimes bring up fake news in discussions about how best to make an argument.

"I'm still figuring out the best strategies just to address it," Figueiredo said. "You hear a lot of people talking about fake news, but I don't know that people buy into it. I wonder if it's a contemporary technique to dismiss a story you don't believe."

At the University of Washington, two professors plan to offer a course this spring on "Calling Bullshit in the Age of Big Data" to help students wade through inaccurate statistical analyses in science, medicine and social sciences.

Meanwhile, some psychologists are trying to understand why people believe information, even when they suspect it is false or misleading. The answer could lie in something called motivated reasoning.

"One of the reasons that fake news is so successful on the internet is that when I see a piece of information and I agree with it, I do not engage in any critical analysis," said Troy Campbell, a professor of marketing at the University of Oregon who researches the psychology of consumer behavior. "You might not look below and say what is the source of that article or let me go type this into Google to see if it is really true or fact-check it. You do not engage in the same quantity and quality of processing around it. Especially if it is not something you agree with and want to agree with."

Campbell has extended his research into the world of "unfalsability," or why people deny facts that don't confirm to their existing world view. The main reason, according to his 2015 study in the Journal of Social Psychology, is that people don't want to confirm facts that make them feel bad about themselves.

Campbell sees this same kind behavior expressing itself in voters who supported Donald Trump, a topic of fascination at the recent meeting of the Society for personal Social and Psychology in Antonio, where Seeker reached Campbell by phone.

"It's been a big point of discussion," he said.

"A lot of reason that people voted for Donald Trump is the feeling that they are being told by modern society that they are bad, dumb, stupid people," Campbell said. "Voting for Donald Trump is affirmation that I am a good person, I am valuable and he is not bad."

Campbell expects that fake news will have a polarizing effect on American society as both sides dismiss arguments from the other without examining information critically. One solution is to take away the reason that people have for disregarding facts.

"What we can do is to make sure that people don't have a motivation to disregard the evidence," Campbell said. "It's not always going to be possible."

The other answer is to rethink how students are taught in school, and question whether it's a good idea to assume that every child's opinion as valid, even if it isn't accurate or correct, Campbell explained.

"I would say it's an important thing to raise people in a way where they do not just trust their gut all the time," he said. "To raise people who identify as critical thinkers."

Now, for something completely different, Mark Marino has another theory of exposing fake news. He's teaching students how to make up their own.

Marino and Talan Memmott just launched "How to Write and Read Fake News: Journalism in the Age of Trump" as part of the UnderAcademy College, an online school of avant-garde studies that leans toward the absurd.

Marino has signed up more than 100 students who are given assignments in how to make fake tweets, write fake news articles by changing a few words in real news articles, and "post-fact-checking" in which students reinforce their stories with made up fact-checking.

Read more at Discovery News

While meeting with congressional leaders Monday, President Trump repeated his claim that several million votes for Hillary Clinton were illegal, despite the lack of evidence and statements to the contrary by elections officials. Trump also claimed that his inauguration brought more than a million people to the National Mall in Washington, despite photographic evidence disproving the statement.

Measuring the impact of fake news spread through Facebook or Twitter is more difficult. Did made-up reports of pre-election ballot-stuffing for Hillary Clinton in Ohio before the election change any votes? Perhaps not, but it did lead the story's original author, a Republican legislative aide in Maryland, to lose his job last week

On many college campuses, professors are teaching their students identify and analyze fake news shared on social media, while some are even teaching students how to write their own fake news stories as a form of satire to make a bigger point about critical thinking.

"It's become such a big part of public discourse," said Sergio Figueiredo, assistant professor of English at Kennesaw State University in Georgia. "Whether its President Trump's press secretary talking about 'alternative facts' or CNN saying it's not going to put out statements from press briefings if not deemed accurate."

Figueiredo, who teaches rhetoric as well as social media writing, say, his students sometimes bring up fake news in discussions about how best to make an argument.

"I'm still figuring out the best strategies just to address it," Figueiredo said. "You hear a lot of people talking about fake news, but I don't know that people buy into it. I wonder if it's a contemporary technique to dismiss a story you don't believe."

At the University of Washington, two professors plan to offer a course this spring on "Calling Bullshit in the Age of Big Data" to help students wade through inaccurate statistical analyses in science, medicine and social sciences.

Meanwhile, some psychologists are trying to understand why people believe information, even when they suspect it is false or misleading. The answer could lie in something called motivated reasoning.

"One of the reasons that fake news is so successful on the internet is that when I see a piece of information and I agree with it, I do not engage in any critical analysis," said Troy Campbell, a professor of marketing at the University of Oregon who researches the psychology of consumer behavior. "You might not look below and say what is the source of that article or let me go type this into Google to see if it is really true or fact-check it. You do not engage in the same quantity and quality of processing around it. Especially if it is not something you agree with and want to agree with."

Campbell has extended his research into the world of "unfalsability," or why people deny facts that don't confirm to their existing world view. The main reason, according to his 2015 study in the Journal of Social Psychology, is that people don't want to confirm facts that make them feel bad about themselves.

Campbell sees this same kind behavior expressing itself in voters who supported Donald Trump, a topic of fascination at the recent meeting of the Society for personal Social and Psychology in Antonio, where Seeker reached Campbell by phone.

"It's been a big point of discussion," he said.

"A lot of reason that people voted for Donald Trump is the feeling that they are being told by modern society that they are bad, dumb, stupid people," Campbell said. "Voting for Donald Trump is affirmation that I am a good person, I am valuable and he is not bad."

Campbell expects that fake news will have a polarizing effect on American society as both sides dismiss arguments from the other without examining information critically. One solution is to take away the reason that people have for disregarding facts.

"What we can do is to make sure that people don't have a motivation to disregard the evidence," Campbell said. "It's not always going to be possible."

The other answer is to rethink how students are taught in school, and question whether it's a good idea to assume that every child's opinion as valid, even if it isn't accurate or correct, Campbell explained.

"I would say it's an important thing to raise people in a way where they do not just trust their gut all the time," he said. "To raise people who identify as critical thinkers."

Now, for something completely different, Mark Marino has another theory of exposing fake news. He's teaching students how to make up their own.

Marino and Talan Memmott just launched "How to Write and Read Fake News: Journalism in the Age of Trump" as part of the UnderAcademy College, an online school of avant-garde studies that leans toward the absurd.

Marino has signed up more than 100 students who are given assignments in how to make fake tweets, write fake news articles by changing a few words in real news articles, and "post-fact-checking" in which students reinforce their stories with made up fact-checking.

Read more at Discovery News

Life Continues Within the Body After Death, Evidence Shows

Even after someone is declared dead, life continues in the body, suggests a surprising new study with important implications.

Gene expression — when information stored in DNA is converted into instructions for making proteins or other molecules — actually increases in some cases after death, according to the new paper, which tracked postmortem activity and is published in the journal Open Biology.

"Not all cells are 'dead' when an organism dies," senior author Peter Noble of the University of Washington and Alabama State University told Seeker. "Different cell types have different life spans, generation times and resilience to extreme stress."

In fact, some cells seem to fight to live after the organism has died.

"It is likely that some cells remain alive and are attempting to repair themselves, specifically stem cells," Noble said.

Signs of Cellular Life

The international team of scientists, led by Alex Pozhitkov, studied zebrafish and mice and believe that the phenomenon occurs in all animals, including humans.

Gene transcription — the first step of gene expression, where a segment of DNA is copied into RNA — associated with stress, immunity, inflammation, cancer and other factors increased after death. And this could happen within hours or even days after the individual as a whole was declared dead.

Interestingly, gene transcription linked to embryonic development also increased. It's as though parts of the body essentially go back in time, exhibiting cellular characteristics of very early human development.

The Twilight of Death

The researchers identified a "step-wise shutdown" after death where some gene transcriptions diminished while others became more abundant. While the precise steps have yet to be defined, the scientists do not believe the process is random.

"Death is a time-dependent process," Noble remarked. "We have framed our discussion of death in reference to 'postmortem time' because on the one hand, there is no reason to suspect that minutes after an animal dies, gene transcription will abruptly stop."

"On the other hand," he added, "we know that within hours to days, the animal's body will eventually decompose by natural processes and gene transcription will end." The authors referred to the window of time between "death and the start of decomposition as the 'twilight of death' — when gene expression occurs, but not all of the cells are dead yet."

For years, researchers have noted that recipients of donor organs, such as livers, often exhibit increased risk of cancer following a transplant. The authors indicate there could be a link between "twilight of death" gene transcription and this increased cancer risk.

"It might be useful to prescreen transplant organs for increased cancer gene transcripts," Noble said, which might offer some insight on the health of the organ, though more research is needed.

If such a connection is established, the findings could help to explain why the donated organs of people who were young and healthy before death — for example, if they died in a sudden accident — could still lead to increased risk of cancer in the organ recipient.

Since gene transcription associated with cancer and inflammation also can increase postmortem, analyzing those activities and patterns could shed light on how these health problems arise in the living and how the body reacts once they have been established.

Ashim Malhotra, an assistant professor at Pacific University Oregon who was not involved with the study, said "one would expect genes involved in immunity and inflammation to [increase in response to a stimulus] right after... death because some cells remain alive for a short time and the transcriptional machinery is still operating in 'life mode.'"

Malhotra was nevertheless surprised that the process happened between 24 to 48 hours after death. The researchers concluded their investigations after that upper time limit, so the transcription could potentially go on for longer than two days.

Perhaps certain cells live longer than we think, but there could be another explanation that has not yet been considered.

Noble likens studying the dead to analyzing building collapses, in that both investigations can reveal what the original underlying structure was.

"Like the twin towers on 9-11, we can get a lot of information on how a system collapses by studying the sequence of events as they unfold through time," he said. "In the case of the twin towers, we saw a systematic collapse of one floor at a time that affected the floors underneath it. This gives us an idea of the structural foundations supporting the building and we see a similar pattern in the shutdown of animals."

Read more at Discovery News

Gene expression — when information stored in DNA is converted into instructions for making proteins or other molecules — actually increases in some cases after death, according to the new paper, which tracked postmortem activity and is published in the journal Open Biology.

"Not all cells are 'dead' when an organism dies," senior author Peter Noble of the University of Washington and Alabama State University told Seeker. "Different cell types have different life spans, generation times and resilience to extreme stress."

In fact, some cells seem to fight to live after the organism has died.

"It is likely that some cells remain alive and are attempting to repair themselves, specifically stem cells," Noble said.

Signs of Cellular Life

The international team of scientists, led by Alex Pozhitkov, studied zebrafish and mice and believe that the phenomenon occurs in all animals, including humans.

Gene transcription — the first step of gene expression, where a segment of DNA is copied into RNA — associated with stress, immunity, inflammation, cancer and other factors increased after death. And this could happen within hours or even days after the individual as a whole was declared dead.

Interestingly, gene transcription linked to embryonic development also increased. It's as though parts of the body essentially go back in time, exhibiting cellular characteristics of very early human development.

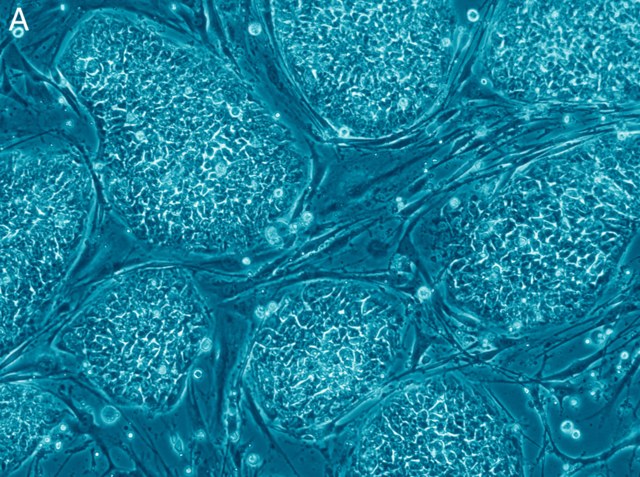

|

| Human embryonic stem cells. |

The researchers identified a "step-wise shutdown" after death where some gene transcriptions diminished while others became more abundant. While the precise steps have yet to be defined, the scientists do not believe the process is random.

"Death is a time-dependent process," Noble remarked. "We have framed our discussion of death in reference to 'postmortem time' because on the one hand, there is no reason to suspect that minutes after an animal dies, gene transcription will abruptly stop."

"On the other hand," he added, "we know that within hours to days, the animal's body will eventually decompose by natural processes and gene transcription will end." The authors referred to the window of time between "death and the start of decomposition as the 'twilight of death' — when gene expression occurs, but not all of the cells are dead yet."

For years, researchers have noted that recipients of donor organs, such as livers, often exhibit increased risk of cancer following a transplant. The authors indicate there could be a link between "twilight of death" gene transcription and this increased cancer risk.

"It might be useful to prescreen transplant organs for increased cancer gene transcripts," Noble said, which might offer some insight on the health of the organ, though more research is needed.

If such a connection is established, the findings could help to explain why the donated organs of people who were young and healthy before death — for example, if they died in a sudden accident — could still lead to increased risk of cancer in the organ recipient.

Since gene transcription associated with cancer and inflammation also can increase postmortem, analyzing those activities and patterns could shed light on how these health problems arise in the living and how the body reacts once they have been established.

Ashim Malhotra, an assistant professor at Pacific University Oregon who was not involved with the study, said "one would expect genes involved in immunity and inflammation to [increase in response to a stimulus] right after... death because some cells remain alive for a short time and the transcriptional machinery is still operating in 'life mode.'"

Malhotra was nevertheless surprised that the process happened between 24 to 48 hours after death. The researchers concluded their investigations after that upper time limit, so the transcription could potentially go on for longer than two days.

Perhaps certain cells live longer than we think, but there could be another explanation that has not yet been considered.

Noble likens studying the dead to analyzing building collapses, in that both investigations can reveal what the original underlying structure was.

"Like the twin towers on 9-11, we can get a lot of information on how a system collapses by studying the sequence of events as they unfold through time," he said. "In the case of the twin towers, we saw a systematic collapse of one floor at a time that affected the floors underneath it. This gives us an idea of the structural foundations supporting the building and we see a similar pattern in the shutdown of animals."

Read more at Discovery News

Lizard Fossil in Montana Reveals a New Dino-Era Species

A famed Montana fossil site has yielded a new species of lizard that lived late in the dinosaur era, some 75 million years ago.

The new species, called Magnuviator ovimonsensis and unearthed at the fossil-rich "Egg Mountain" site in Montana, will help scientists better understand how lizards evolved during the days when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, say researchers who made the discovery. The team, from the University of Washington (UW), Montana State University and the Burke Museum of Natural History & Culture, published its findings on the new lizard in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

All told, two nearly complete fossil skeletons of the species were recovered. The samples were subjected to multiple rounds of CT scans – one to distinguish the skeletons from the rock that encased them, and others to fashion digital recreations of the skulls of the creatures.

Analysis of the ancient animal's anatomy told the scientists it was a new species, one that most closely resembled Cretaceous iguanians from far-off Mongolia and not other fossil lizards from the Americas. Magnuviator, then, was more like an evolutionary offshoot, or "stem," of iguanian lizards, they said - "at best" a distant relative of modern lizards such as chameleons and anoles.

"These ancient lineages are not the iguanian lizards which dominate parts of the Americas today, such as anoles and horned lizards," explained lead author David DeMar, of UW, in a statement. "So discoveries like Magnuviator give us a rare glimpse into the types of 'stem' lizards that were present before the extinction of the dinosaurs."

The researchers named their find In honor of the famous location where it was discovered. Magnuviator ovimonsensis translates to "mighty traveler from Egg Mountain."

The world's first discovery of dinosaur embryos was made at Egg Mountain, and the first baby dinosaur fossils came from the site a well. Thought to have been dry and arid 75 million years ago, the site has also yielded wasp pupae cases and pollen grains from plants.

The researchers think, based on Magnuviator's teeth and the diet of some modern lizards, that the ancient lizard might have dined on such wasps at Egg Mountain, although they allow that it could have been eating other things, given its relatively large size of 14 inches long.

"Due to the significant metabolic requirements to digest plant material, only lizards above a certain body size can eat plants, and Magnuviator definitely falls within that size range," said DeMar.

Read more at Discovery News

The new species, called Magnuviator ovimonsensis and unearthed at the fossil-rich "Egg Mountain" site in Montana, will help scientists better understand how lizards evolved during the days when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, say researchers who made the discovery. The team, from the University of Washington (UW), Montana State University and the Burke Museum of Natural History & Culture, published its findings on the new lizard in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

All told, two nearly complete fossil skeletons of the species were recovered. The samples were subjected to multiple rounds of CT scans – one to distinguish the skeletons from the rock that encased them, and others to fashion digital recreations of the skulls of the creatures.

Analysis of the ancient animal's anatomy told the scientists it was a new species, one that most closely resembled Cretaceous iguanians from far-off Mongolia and not other fossil lizards from the Americas. Magnuviator, then, was more like an evolutionary offshoot, or "stem," of iguanian lizards, they said - "at best" a distant relative of modern lizards such as chameleons and anoles.

"These ancient lineages are not the iguanian lizards which dominate parts of the Americas today, such as anoles and horned lizards," explained lead author David DeMar, of UW, in a statement. "So discoveries like Magnuviator give us a rare glimpse into the types of 'stem' lizards that were present before the extinction of the dinosaurs."

The researchers named their find In honor of the famous location where it was discovered. Magnuviator ovimonsensis translates to "mighty traveler from Egg Mountain."

The world's first discovery of dinosaur embryos was made at Egg Mountain, and the first baby dinosaur fossils came from the site a well. Thought to have been dry and arid 75 million years ago, the site has also yielded wasp pupae cases and pollen grains from plants.

The researchers think, based on Magnuviator's teeth and the diet of some modern lizards, that the ancient lizard might have dined on such wasps at Egg Mountain, although they allow that it could have been eating other things, given its relatively large size of 14 inches long.

"Due to the significant metabolic requirements to digest plant material, only lizards above a certain body size can eat plants, and Magnuviator definitely falls within that size range," said DeMar.

Read more at Discovery News

Jan 22, 2017

Why the lights don't dim when we blink

|

| New study finds that blinking steadies our gaze. |

Scientists at UC Berkeley, Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, Université Paris Descartes and Dartmouth College have found that blinking does more than lubricate dry eyes and protect them from irritants. In a study published in today's online edition of the journal Current Biology, they found that when we blink, our brain repositions our eyeballs so we can stay focused on what we're viewing.

When our eyeballs roll back in their sockets during a blink, they don't always return to the same spot when we reopen our eyes. This misalignment prompts the brain to activate the eye muscles to realign our vision, said study lead author Gerrit Maus, an assistant professor of psychology at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. He launched the study as a postdoctoral fellow in UC Berkeley's Whitney Laboratory for Perception and Action.

"Our eye muscles are quite sluggish and imprecise, so the brain needs to constantly adapt its motor signals to make sure our eyes are pointing where they're supposed to," Maus said. "Our findings suggest that the brain gauges the difference in what we see before and after a blink, and commands the eye muscles to make the needed corrections."

From a big-picture perspective, if we didn't possess this powerful oculomotor mechanism, particularly when blinking, our surroundings would appear shadowy, erratic and jittery, researchers said.

"We perceive coherence and not transient blindness because the brain connects the dots for us," said study co-author David Whitney, a psychology professor at UC Berkeley.

"Our brains do a lot of prediction to compensate for how we move around in the world," said co-author Patrick Cavanagh, a professor of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth College. "It's like a steadicam of the mind."

A dozen healthy young adults participated in what Maus jokingly called "the most boring experiment ever." Study participants sat in a dark room for long periods staring at a dot on a screen while infrared cameras tracked their eye movements and eye blinks in real time.

Every time they blinked, the dot was moved one centimeter to the right. While participants failed to notice the subtle shift, the brain's oculomotor system registered the movement and learned to reposition the line of vision squarely on the dot.

After 30 or so blink-synchronized dot movements, participants' eyes adjusted during each blink and shifted automatically to the spot where they predicted the dot to be.

Read more at Science Daily

Ultrafast Camera Captures 'Sonic Booms' of Light for First Time

Just as aircraft flying at supersonic speeds create cone-shaped sonic booms, pulses of light can leave behind cone-shaped wakes of light. Now, a superfast camera has captured the first-ever video of these events.

The new technology used to make this discovery could one day allow scientists to help watch neurons fire and image live activity in the brain, researchers say.

When an object moves through air, it propels the air in front of it away, creating pressure waves that move at the speed of sound in all directions. If the object is moving at speeds equal to or greater than sound, it outruns those pressure waves. As a result, the pressure waves from these speeding objects pile up on top of each other to create shock waves known as sonic booms, which are akin to claps of thunder.

Sonic booms are confined to conical regions known as "Mach cones" that extend primarily to the rear of supersonic objects. Similar events include the V-shaped bow waves that a boat can generate when traveling faster than the waves it pushes out of its way move across the water.

Previous research suggested that light can generate conical wakes similar to sonic booms. Now, for the first time, scientists have imaged these elusive "photonic Mach cones."

Light travels at a speed of about 186,000 miles per second (300,000 kilometers per second) when moving through vacuum. According to Einstein's theory of relativity, nothing can travel faster than the speed of light in a vacuum. However, light can travel more slowly than its top speed — for instance, light moves through glass at speeds of about 60 percent of its maximum. Indeed, prior experiments have slowed light down more than a million-fold.

The fact that light can travel faster in one material than in another helped scientists to generate photonic Mach cones. First,study lead author Jinyang Liang, an optical engineer at Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues designed a narrow tunnel filled with dry ice fog. This tunnel was sandwiched between plates made of a mixture of silicone rubber and aluminum oxide powder.

Then, the researchers fired pulses of green laser light — each lasting only 7 picoseconds (trillionths of a second) — down the tunnel. These pulses could scatter off the specks of dry ice within the tunnel, generating light waves that could enter the surrounding plates.

The green light that the scientists used traveled faster inside the tunnel than it did in the plates. As such, as a laser pulse moved down the tunnel, it left a cone of slower-moving overlapping light waves behind it within the plates.

To capture video of these elusive light-scattering events, the researchers developed a "streak camera" that could capture images at speeds of 100 billion frames per second in a single exposure. This new camera captured three different views of the phenomenon: one that acquired a direct image of the scene, and two that recorded temporal information of the events so that the scientists could reconstruct what happened frame by frame.

Essentially, they "put different bar codes on each individual image, so that even if during the data acquisition they are all mixed together, we can sort them out," Liang said in an interview.

There are other imaging systems that can capture ultrafast events, but these systems usually need to record hundreds or thousands of exposures of such phenomena before they can see them. In contrast, the new system can record ultrafast events with just a single exposure.

Read more at Discovery News

The new technology used to make this discovery could one day allow scientists to help watch neurons fire and image live activity in the brain, researchers say.

When an object moves through air, it propels the air in front of it away, creating pressure waves that move at the speed of sound in all directions. If the object is moving at speeds equal to or greater than sound, it outruns those pressure waves. As a result, the pressure waves from these speeding objects pile up on top of each other to create shock waves known as sonic booms, which are akin to claps of thunder.

Sonic booms are confined to conical regions known as "Mach cones" that extend primarily to the rear of supersonic objects. Similar events include the V-shaped bow waves that a boat can generate when traveling faster than the waves it pushes out of its way move across the water.

Previous research suggested that light can generate conical wakes similar to sonic booms. Now, for the first time, scientists have imaged these elusive "photonic Mach cones."

Light travels at a speed of about 186,000 miles per second (300,000 kilometers per second) when moving through vacuum. According to Einstein's theory of relativity, nothing can travel faster than the speed of light in a vacuum. However, light can travel more slowly than its top speed — for instance, light moves through glass at speeds of about 60 percent of its maximum. Indeed, prior experiments have slowed light down more than a million-fold.

The fact that light can travel faster in one material than in another helped scientists to generate photonic Mach cones. First,study lead author Jinyang Liang, an optical engineer at Washington University in St. Louis, and his colleagues designed a narrow tunnel filled with dry ice fog. This tunnel was sandwiched between plates made of a mixture of silicone rubber and aluminum oxide powder.

Then, the researchers fired pulses of green laser light — each lasting only 7 picoseconds (trillionths of a second) — down the tunnel. These pulses could scatter off the specks of dry ice within the tunnel, generating light waves that could enter the surrounding plates.

The green light that the scientists used traveled faster inside the tunnel than it did in the plates. As such, as a laser pulse moved down the tunnel, it left a cone of slower-moving overlapping light waves behind it within the plates.

To capture video of these elusive light-scattering events, the researchers developed a "streak camera" that could capture images at speeds of 100 billion frames per second in a single exposure. This new camera captured three different views of the phenomenon: one that acquired a direct image of the scene, and two that recorded temporal information of the events so that the scientists could reconstruct what happened frame by frame.

Essentially, they "put different bar codes on each individual image, so that even if during the data acquisition they are all mixed together, we can sort them out," Liang said in an interview.

There are other imaging systems that can capture ultrafast events, but these systems usually need to record hundreds or thousands of exposures of such phenomena before they can see them. In contrast, the new system can record ultrafast events with just a single exposure.

Read more at Discovery News

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)