The findings, reported in the journal PLOS ONE, show how quickly animals can adapt to getting ahold of prey, and could offer humans with surprising benefits in the future.

Long-fingered bats (Myotis capaccinii) from Europe can instinctively grab fish with their long digits, the first study found. For years, the bats were thought to eat only insects, but they were not about to pass up an opportunity for easy eats when it became available.

"The only ponds we know the long-fingered bats regularly fish in are artificial pools that were built in 2002," lead author Ostaizka Aizpurua, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Copenhagen's Natural History Museum of Denmark, told Seeker. She explained that the ponds are located at a golf course near Dénia, Spain.

"Interestingly," she added, "the first evidence of fish consumption was reported in 2003, suggesting that as soon as a high density of surface-feeder fish became available, bats were able to catch them."

Aizpurua and her colleagues observed the bats practice "trawling," where they drag their long digits in fish-filled water, going deeper if needed. When fish disappear under the water in an attempt to hide, this actually seems to stimulate the bat's hunting drive all the more.

The researchers also studied a population of strictly insect-eating long-fingered bats from a stream pool near Ròtova, Spain. While both bat groups were capable of similar modes of attack, the golf course bats had more exaggerated trawling moves, suggesting that they had previously honed their technique to improve their chances of catching fish, instead of just insects.

The good news for humans is that the fish are surface-feeders known as Gambusia holbrooki. Originally from America, they are an invasive species in Europe, so the bat fishing is a win-win: bats get a belly-full of nutritious food, while people gain a natural remover of the pesky fish.

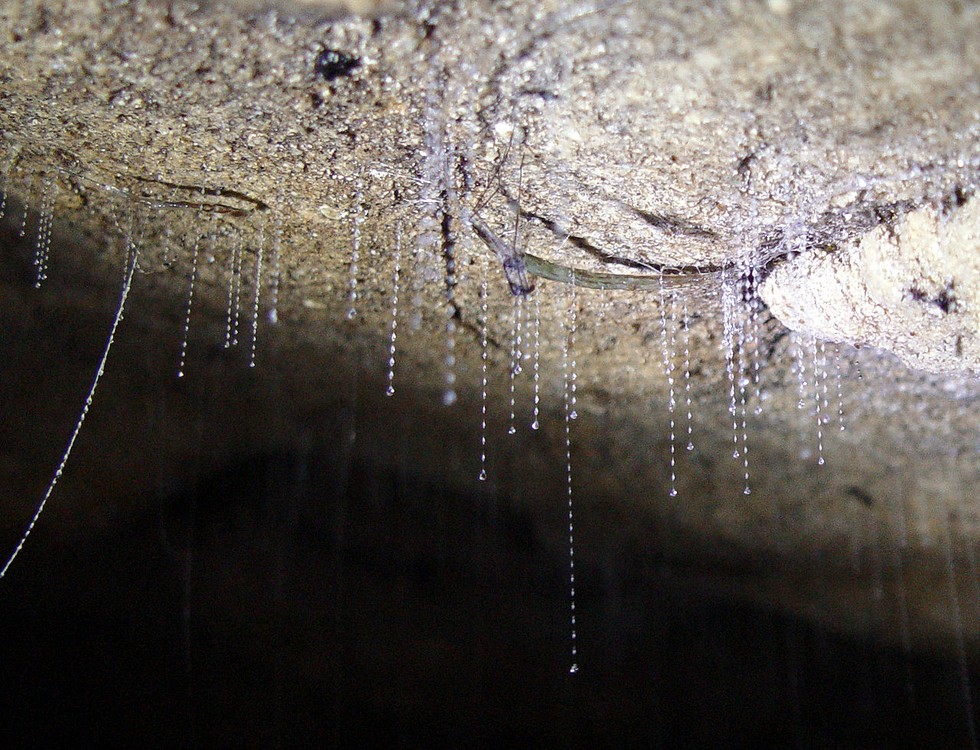

The second paper describing an unusual animal mode of fishing focused on New Zealand Arachnocampa glowworms, which are actually a type of larvae that trap prey with sticky fishing lines of their own creation. The glowing tail light attracts prey, often mayflies, which get tangled up in the fishing lines.

|

| Arachnocampa glowworm fishing lines in New Zealand. |

The process begins with the glowworms releasing the fishing lines from their mouth. Analyzing the components of the lines from two caves on New Zealand's North Island, the scientists found that they contain water, proteins, fats and, to their surprise, the insect's own urine. While more tests are needed to confirm this, urine now makes sense as a component, because it can contain moisture-absorbing salts.

While rather unappetizing to contemplate, the glowworm eats the curtain of fishing lines—urine and all—once they have been used. The extra water drawn in by urea, the main product in urine, probably helps the glowworms avoid desiccation.

A clever aspect of the system is that a glowworm fishing line can only hold the weight of three mayflies before it breaks.

"This makes sense, because this limits the risk of too much prey being caught," von Byern said. "Otherwise, the whole nest may collapse, tearing off the cave wall and falling with the larva into the river below."

Yet another clever aspect is that the fishing lines are only "activated" when the humidity is over 80 percent. When dry, they are not sticky, and so do not trap prey.

As for how all of this could benefit people too, von Byern points out that a popular wood adhesive used to be made out of urea and formaldehyde. It was very simple, effective and cheap to make, but formaldehyde in the product was banned due to health concerns.

Read more at Discovery News

No comments:

Post a Comment