|

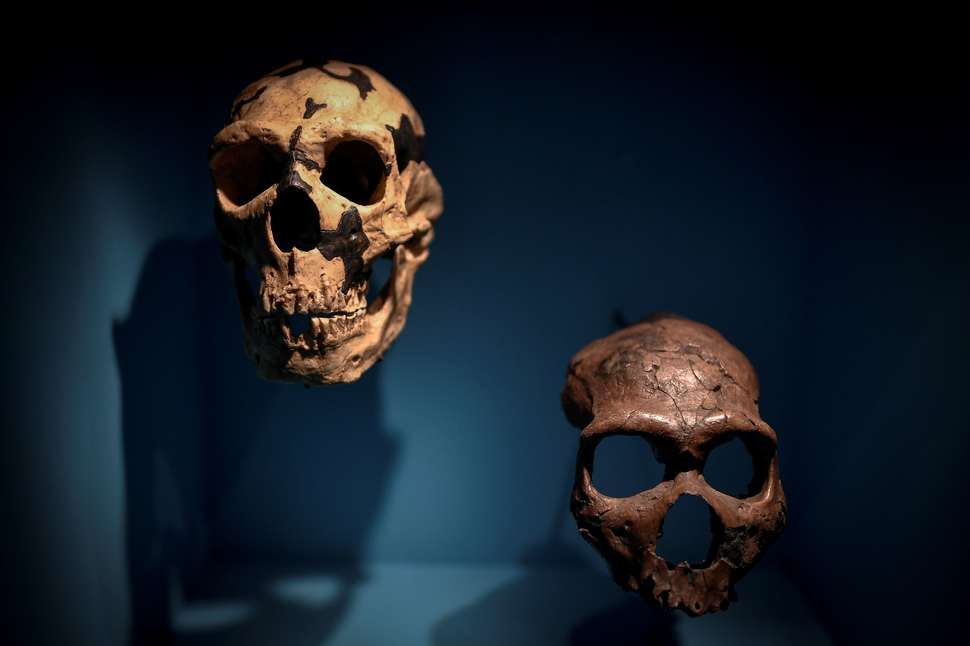

| Skulls are displayed as part of the Neanderthal exhibition at the Musee de l'Homme in Paris on March 26, 2018. |

There are rare cases of ancient brains, such as the 2,600-year-old Heslington Brain, being found "pickled" in certain wet, anoxic environments, but prehistoric brains in the archaeological record are very few.

Scientists therefore lack intact Neanderthal and early Homo sapiens brains to study. But an innovative team has just reconstructed such brains using a technique called computational neuroanatomy. The 3D models they produced, reported in the journal Scientific Reports, are the first of their kind.

"Our attempt to actually reconstruct the brain inside of the fossil crania is completely new to the field," co-author Naomichi Ogihara of Keio University's Department of Mechanical Engineering told Seeker.

Ogihara, co-senior authors Norihiro Sadato and Takeru Akazawa, and their colleagues used virtual casts of four Neanderthal and four early Homo sapiens skull fossils to reconstruct the size of their brains. The Neanderthals lived in what are now Israel, France, and Gibraltar. The early Homo sapiens came from Israel and the Czech Republic.

The authors then used MRI data from the brains of 1,185 living humans to model the average human brain. They also considered non-human primate brains and the skull of a Cro-Magnon individual who lived 32,000 years ago.

The resulting computer model was then deformed to match the shape of the Neanderthal and early Homo sapiens skull casts. This allowed the researchers to predict what the brains of these humans might have looked like, and how individual brain regions could have differed between the two groups.

It should be noted that many researchers believe Neanderthals were members of our species. Ogihara told Seeker there is ample evidence "showing that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens interbred. We believe so, too."

As a result, the majority of people alive today retain Neanderthal DNA. These include people whose heritage is North African, as well as people with Eurasian ancestry.

It is even possible that the early modern humans included in the study were related to Neanderthals.

“We certainly cannot deny the possibility that the specimens we used already interbred with Neanderthals,” Ogihara told Seeker.

But, he added, “there is no obvious reason to think that way, so we basically assumed that the individuals used in the present study had not interbred with Neanderthals.”

The computer models confirmed prior findings that Neanderthal brains were larger than those of anatomically modern humans. The researchers, however, do not believe that bigger is always better when it comes to brains.

The international team concluded that Neanderthals and early modern humans possessed significantly different brain morphologies, including the latter having a larger cerebellum. Since this part of the brain is associated with language comprehension and production, working memory, and cognitive flexibility, the researchers believe that early modern humans were superior to Neanderthals in terms of these abilities.

"We are not saying that Neanderthals were incapable of processing languages," Ogihara said. "We think they could communicate verbally, but their social ability using languages was probably limited because of the brain structural differences."

It is possible that Neanderthals relied more on visual information. They are thought to have been the world's first artists. The earliest known cave art, reported this year, consists of 65,000-year-old paintings found in three Neanderthal caves in Spain.

Ogihara and his colleagues determined that Neanderthals had a larger occipital lobe than did early modern humans.

"The occipital lobe is the visual processing center," Ogihara explained. "Neanderthals possibly required the larger occipital lobe to compensate for low light levels in Europe."

Because of this, Neanderthals may have been unable to evolve the cerebellum expansion seen in early modern humans.

Brain comparison studies come with inherent challenges, as even brains within a particular species today are not the same. The brains of male humans, for example, tend to be slightly larger than those of females, but the majority of scientists believe that brain size does not necessarily correlate with intelligence.

A bigger Neanderthal brain does not appear to have been advantageous when early modern humans began to dominate their former territories. While Neanderthals — via their DNA — were absorbed into modern Homo sapiens to a certain extent, their extinction is widely believed to have begun around 40,000 years ago. This period coincides with greater numbers of early modern humans migrating into Eurasia.

Ogihara said that his team's research cannot definitively conclude what led to the disappearance of Neanderthals. But, he said, the study shows innate morphological differences in the brain structure actually existed between Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens, which possibly led to differences in cognitive and social abilities.

"Although the difference could be subtle,” he said, “such a subtle difference may become significant in terms of natural selection."

The jury is still out on Neanderthal brain power. Joao Zilhao of the Catalan Institute for Research and Advanced Studies was a member of the team that reported the Neanderthal cave art.

Zilhao told Seeker that both Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens must have possessed the cognitive hardware required for advanced symbolic behavior, such as cave art and body ornamentation.

“The fact that we find the capability in both Neandertals and early modern humans implies that said capability existed in the common ancestor around 500,000 years ago,” he said. “Ergo, I would think it entirely logical to consider that the null hypothesis is the co-evolution of brain, language, and symbolic thinking, and that the fundamentals of human cognition as we know it were in place ever since we see people with big brains in the fossil record — i.e., since at least 1.5 million years ago."

Read more at Seeker

No comments:

Post a Comment